Japan’s pre-modern warrior elite can’t still be alive inside the suits of armour that hold you awed and scared in this scintillating journey through their world of gore, power and artistic beauty. But they surely seem to be: samurai armour is so vital, so electric, with its grimacing, moustached, black face masks and full-body metal and fabric plating. The crests of their helmets incorporate eagles, dragons, goblins, even a clenched fist of metal emerging from one warrior’s head. It’s so intense you feel a presence.

Menace … a 17th century suit of armour with bullet-proof cuirass. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

Then again, the samurai always were ghosts in their suits. The metal mask became their face to the world, their carapaces transformed them into someone else. This idea that in battle the warrior becomes other, a bloody demon, is not unique to Japan: Viking “berserkers” lost themselves in a ritualised frenzy and may have believed they changed into bears. Armour in medieval Europe, too, was never just practical but a second skin, a full metal jacket suppressing softness and symbolising the steely transfiguration of normal souls into killers. But no culture has ever put quite as much creativity into blood-lust as Japan did from the 13th century – when samurai courage saw off Mongol invaders – until the abolition of this class in the 1800s.

One of these eerily inhabited cyborg armours has been lent by the Royal Collection. It was was a gift for James VI of Scotland and I of England by a son of the second shōgun of the Tokugawa dynasty – but a barbed gift. Opulently crafted from lacquer, silk, deerskin and metal, its surface pulses with menace and mystery. It sent a clear message to far-off Britain: mess with us at your peril.

That was no idle threat. Painted screens, scrolls and books depict samurai armies in action. A rider in a samurai battle scene by Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu is studded with arrows but they’ve lodged harmlessly in his thick armour. His unprotected horse, however, bleeds from an arrow wound near its heart. On the ground, a warrior lies in glorious armour that is no use to him now, for his head has been cut off. So that’s what those elegant blades with their sweeping curvature – displayed nearby – are for.

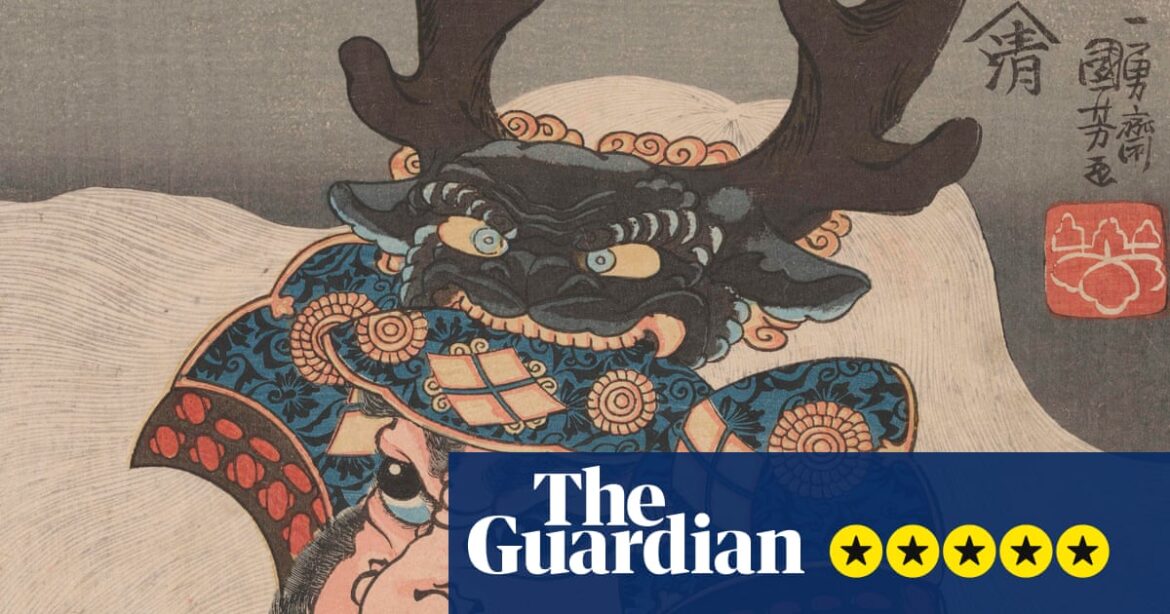

Minamoto no Tametomo on the Isle of Demons, by Katsushika Hokusai. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum’s exhibition, however, does not just honour the art of war but embraces love and peace. We meet the warlord with a song in his heart. In a 19th-century painting by Kano Eishun, a samurai literally takes time to smell the flowers as he rides among orange blossoms. And it was samurai nobles who were the most prestigious clients of early modern Edo’s pleasure quarter, the “floating world”. In a painting from Chōbunsai Eishi’s 1790s handscroll, Twelve Erotic Scenes in Edo, we see the silhouette of a samurai making love to a courtesan behind a screen while in the foreground two women caress the shiny blade of his long unsheathed sword.

Maybe this perverse piece of shunga art goes to the heart of this exhibition’s appeal. Samurai warfare was violent yet theatrical, cruel but glamorous, lethal but sexy. Before a samurai blade sliced you up, their demonic appearance held you transfixed.

You feel bereft when you reach the abolition of the samurai elite as Japan in the 1800s tried to modernise. Photographs of the last samurai seem to show the passing of something wondrous from the world. And when the 20th century released new horrors of mechanised mass warfare there was no place left for myth or chivalry. In the west and east, the rituals and costumed theatrics that were part of feudal societies were irrelevant, especially after the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Modern times … Duck and Man 2025, by Noguchi Tetsuya. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

So the exhibition’s finale is inevitably disappointing. You meet a lifesized Darth Vader, touted here as a modern-day samurai but for me not as scary or mysterious as the originals. More to the point is a display on Yukio Mishima, as he is known to the west, whose novels explored the appeal of samurai violence and passion in a banal, commodified modern world, before he left it by committing seppuku, a traditional ritual of self-disembowelment.

The samurai emerge here as so much more than killers: as patrons of the arts, sensitive to nature, masters of civilised ways. And yet I’d trade it all to see a samurai charge. The ghosts of dead warriors inside their empty suits dominate the show. There are many forms of artistry here but nothing is more expressive than these portraits in steel, silk and lacquer. It’s an extraordinary encounter. Samurai armour embodies a merciless truth about the human condition and what it can become.

Samurai runs at the British Museum, London, 3 February-4 May

AloJapan.com