Three main factors contribute to LAND subsidence in these four imperial gardens. Frist, subsidence of traditional palace buildings and white sand courtyards may be attributed to Holocene depositional environments.

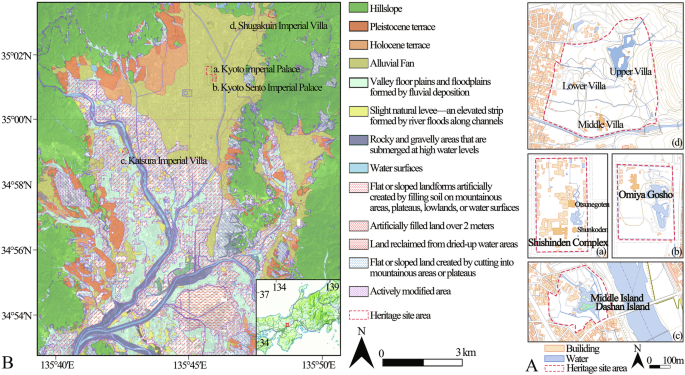

Before 794, the Kyoto Basin, in which Kyoto Gyoen is situated, frequently experienced flooding from its rivers. After the Heian period began, the reduction of floodplains allowed the aristocratic Reizei family established a garden within the present-day grounds of the Kyoto Imperial Palace during the Heian period (794–1185). The garden has become renowned for its use of spring water gushing from the ground as a key landscape feature. This site served as an imperial garden since 1331. After Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Kyoto in 1603, the area underwent large-scale expansion and infill construction, including the development of palace buildings and gardens. The fires of 1708 and 1788 caused extensive damage, resulting in the accumulation of burnt debris and flood-borne sediments across the site. Reconstruction took place in 1790. Another major fire in 1854 destroyed most of the palace complexes again. Reconstruction began in 1855, largely replicating the layout established during rebuilding in 1790. This reconstruction laid the foundation for most of the existing buildings, including the Shishinden. After the capital was moved to Tokyo in 1869, this site was neglected. In 1877, the grounds underwent renovation through soil covering and regrading, accompanied by the construction of earthen and stone walls, as well as the development of roads around the garden. Since 1992, the Kyoto Imperial Palace has discontinued use of the Kamo River water supply system established in 1912 and has switched to a groundwater system to support pond maintenance and landscape irrigation within the garden.

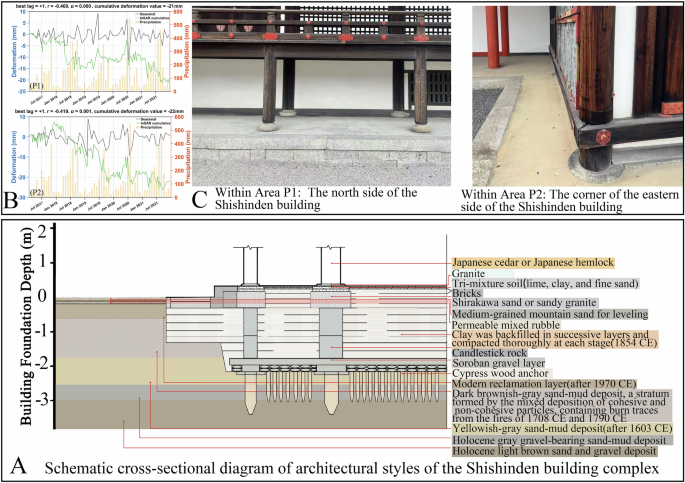

Based on InSAR results, several subsiding points were detected on the northern side of the main building and the corner areas of the auxiliary buildings within the Shishinden building complex (Fig. 6A). Based on borehole investigation reports55, traditional Japanese timber construction standards56, and records on the conservation of cultural heritage buildings57, a schematic cross-sectional diagram was drawn to illustrate the main structural composition of the representative Shishinden building complex and its surrounding courtyard within the Kyoto Imperial Palace (Fig. 7A). The schematic diagram represents the typical foundation construction methods and the subsoil composition of most palace buildings and white sand courtyard.

Fig. 7: Schematic cross-section and deformation analysis within the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

A Schematic cross-section of the foundation of the Shishinden building complex. B STL decomposition60,81 of monthly deformation–precipitation and time series of points for P1(the northeast corner of the Shishinden building) and P2 (north side of the Shishinden building). C Field photographs of the P1 and P2 areas.

The building foundations employed traditional architectural techniques introduced from China, including the use of layered rammed-earth platforms. Foundation stones were placed above the platform to resist moisture and distribute the structural load evenly. The load was then transferred upward through the column bases and horizontal beams to the roof structure. The lower part of the foundation incorporates the kaku-tatami (grid raft) foundation method—a traditional Japanese technique introduced during the 1855 reconstruction to enhance seismic stability.

The courtyard section primarily features a surface layer ~2–3 cm thick of white sand, underlain by a leveling layer composed of either clean sand or mixed sandy soil, and a lower layer of compacted foundation or gravel bedding to ensure proper drainage and structural stability. And the foundations of the buildings and courtyards are situated within thick Holocene deposits, consisting of clay, silt, and fine sand (Fig. 7A).

Numerous studies have shown that historical heritage sites constructed over many generations located on Late Pleistocene to Holocene environments—such as alluvial fan plains, lakes, marshes, and deltas—are prone to land subsidence. This is primarily due to the presence of thick Late Pleistocene to Holocene sediments in the subsoil, especially after artificial fill such as successive platform reinforcements, post-disaster backfilling, and landscape ground leveling, which are susceptible to long-term land subsidence4,19,58.

Unlike Katsura and Shugakuin Imperial Villa, where small-diameter timber is commonly used to express lightness and natural beauty, the palace buildings of the Kyoto Imperial Palace are constructed with large load-bearing wooden columns made of Japanese cedar or fir, reflecting a sense of solemnity. The prolonged structural load, together with the Holocene depositional environment, may render the palace buildings susceptible to land subsidence. Field investigation revealed that at P1(the northeast corner of the Shishinden building complex) and P2 (north side of the Shishinden building) (Fig. 6a), long cracks have developed, and multiple visible cracks extend outward from the buildings across the platform base (Fig. 7C). According to official past repair reports, it has been confirmed that cracks in many palace buildings within the Kyoto Imperial Palace have been widening gradually over time.

To further investigate the deformation characteristics, the time series was analyzed based on Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess (STL). STL decomposition results show that the seasonal deformation component in the P1 and P2 areas is significantly negatively correlated with monthly rainfall, with an approximate one-month response lag (Fig. 7B). This indicates that intensive rainfall events, after recharging groundwater and increasing soil moisture content, can lead to delayed surface subsidence, a phenomenon may related to the time required for groundwater infiltration and pressure transmission59,60,61. As rainfall infiltrates through the courtyard’s white-sand pavement (originally designed to minimize surface water retention and allow rapid percolation) and the foundation cracks of building platforms into the underlying soil, it causes a sudden rise in pore-water pressure, which may accelerate the rate of subsidence62,63.

The current conservation strategy follows the principle of “preserving existing conditions and respecting original materials.” Initial assessments are conducted through visual inspections to identify visible deterioration, such as cracks and structural collapse. Restoration is undertaken only when these issues are deemed to pose an evident threat to the building or the courtyard. During regular conditions, only minimal interventions are performed as part of routine maintenance. Consequently, bold splicing marks have appeared on some columns where no joints were originally required, or small metal nails and other materials have been added to maintain structural stability. It is recommended to inspect the structural damage and the elevation of column base stones within the affected area, and to implement preventive conservation measures in a timely manner to address limitations in current traditional restoration strategies. Furthermore, regular inspection of the drainage infrastructure surrounding the courtyards and palace buildings is advised, with particular attention given during the rainy season.

The Sento Imperial Palace is adjacent to the Kyoto Imperial Palace and shares similar historical development and stratigraphic characteristics (Fig. 1B). Initially used by aristocrats, the garden was constructed in 1630 by a retired emperor. Most buildings were reconstructed after a fire in 1855. The buildings within the Sento Imperial Palace are concentrated in the Omiya Palace complex, whereas the other areas contain relatively few artificial hardscape features (Fig. 6B). During this survey, it was observed that base reinforcements such as more ne-maki kanamono (metal fittings at column bases) were added to the main building of the Sento Imperial Palace, especially the Omiya Palace (Fig. 6a), and the Otsunegoten Building in the Kyoto Imperial Palace (Fig. 1a). Steel support tall columns were also installed under the eaves to enhance structural stability and prevent further subsidence or displacement. However, these reinforcements have, to some extent, compromised the classical landscape appearance of the gardens. In the reinforced areas, no significant subsidence was detected in the InSAR results (Fig. 6A, B).

Second, the subsidence observed in Katsura Imperial Villa may be caused by thick Holocene deposits beneath foundations constructed under lake excavation, hill construction, and stonework methods.

Katsura Imperial Villa is located on the west bank of the Katsura River and covers an area of 69,400 m2. During the 10th–11th centuries, it served as a villa for the Fujiwara family. Owing to its slightly elevated riverine sandbar terrain and renowned moonlit scenery, it remained a favored retreat for aristocrats to enjoy moon viewing throughout the centuries. Around 1615, Prince Hachijō Toshihito began constructing the detached palace on this site, excavating lakes, hills constriction, building halls, and laying out stone-paved garden paths64. By ~1662, the layout had nearly assumed its current form. Since its establishment, the buildings of the Katsura Imperial Villa have never suffered from fire, allowing the estate to preserve its historical appearance. The garden’s designers first excavated the Katsura River floodplain to create the “Gyokusui Pond.” The excavated soil was artificially backfilled nearby to form Oyama Island and two lingzhi-shaped central islets (also known as “Shinsen Islands”)65. Oyama Island has a larger height and area than the other islets, making it the highest point in the garden, and it is surrounded by relatively deep pond water. In addition, during the construction of the garden, an “inner canal” was excavated on the eastern side of the site. The western side of this canal became the present-day Shōkintei area, which was largely preserved as a land area66,67, with relatively shallow water surrounding it (Fig. 1c). At the highest point on the northern part of Oyama Island, a flower-viewing pavilion and its associated courtyard (P3) were constructed, while on the lower, flatter southern part of the island, a Garden Hall and its associated courtyard (P4) were built (Fig. 6c).

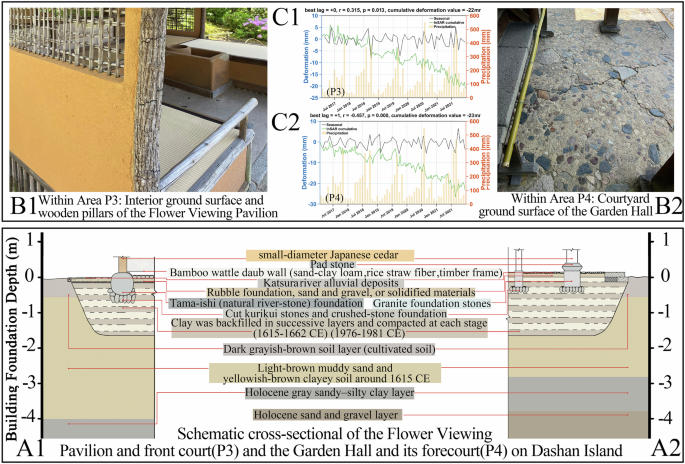

According to the InSAR results, a concentration of subsidence points was observed on Oyama Island. In contrast, the smaller central islands, primarily composed of vegetation and scattered stones for landscaping, had fewer high-coherence points; thus, no subsidence was detected (Fig. 6C). Based on the Kyoto Katsura Imperial Villa Photographic and Surveyed Drawings Collection, borehole investigation reports55, records from the Imperial Household Agency, and architectural preservation reports68, cross-sectional diagrams were drawn illustrating the Flower Viewing Pavilion and Garden Hall, along with courtyard paving (Fig. 8A). It was found that the building and courtyard foundations are primarily situated on thick Holocene fluvial terrace deposits, which are highly compressible and may be prone to subsidence4,19,58. The upper layer primarily consists of light-brown muddy sand and yellowish-brown clayey soil, which were artificially backfilled during the “lake excavation and piling of excavated soil” process. The lower layer comprises Late Pleistocene to Holocene fluvial terrace deposits, with localized intercalations of silt or clay layers. The overall stratigraphy presents an uneven interbedding of sand and mud. In the artificial landscape, the foundations are in direct contact with the sedimentary layers.

Fig. 8: Schematic cross-section and deformation analysis within Katsura Imperial Villa.

Schematic cross-section of the foundation of A1 The Flower Viewing Pavilion and A2 The Garden Hall buildings along with the courtyard paving. B Time series and STL decomposition60,81 of monthly deformation–precipitation of points for P3 (The Flower Viewing Pavilion along with the courtyard) and P4 (The Garden Hall along with the courtyard paving). C Field photographs of P3 and P4 area.

The foundation of the flower-viewing pavilion follows the typical buseki-dodai-shiki method, in which each column base rests directly on a large individual cornerstone (kiso-ishi). Crushed granite stones (wari-kurii) were used underneath for stabilization and drainage. At the base of the wall, crushed stones were similarly used as supports, with a neatly placed wooden sill above to bear the weight of the earthen wall (Fig. 8A1).

The foundation of the Garden Hall primarily employs a stone placement method, utilizing cut rectangular stones as individual cornerstones (kiso-ishi), upon which dōsō-ishi (top stones) are laid. Wooden columns were placed directly on top of the stones (Fig. 8A2). The foundation construction methods used for these two buildings have been widely applied in historical architecture within both the Katsura Imperial Villa and Shugakuin Imperial Villa. Moreover, their foundations did not adopt the kaku-bari (grid raft) foundation method, which became common in the 19th century to support heavier buildings, such as the Shishinden building in the Kyoto Imperial Palace, temple halls, or central palace structures69.

The courtyard paving and garden path arrangements around the buildings were designed to harmonize with the architectural layout of the foundations. Before laying the paving stones, the landscape designer employs foundation techniques, similar to those used in building construction, by placing a layer of gravel as a bed to facilitate drainage. The upper stones are vertically embedded and closely interlocked with the underlying soil and gravel, forming a relatively stable structure. Mortar and cement are not used or permitted69. This method is similar to the construction techniques used in the Arare-Koboshi path on the northern side of the Katsura Imperial Villa.

Past repair reports of the Katsura Imperial Villa indicate that due to rainfall and historical changes have contributed to land subsidence, resulting in unevenness or cracking of the stone paving surfaces made of gravel. Based on the relationship between the STL-derived seasonal deformation component and monthly rainfall, it is observed that, unlike the plains (P1, P2) and the low-lying Garden Hall area of the artificial island (P4), which exhibit a moderate negative correlation with rainfall with a lag of about one month—the hilltop area near the Flower Viewing Pavilion (P3) shows a weak positive correlation without significant delay. This suggests that during intense rainfall events, rapid infiltration into the sandy–clayey backfill may induce short-term wetting expansion, manifested as transient uplift, whereas more favorable drainage conditions than in lower-lying areas may prevent a significant lag effect. Similar phenomena have also been reported in previous studies70,71,72. Based on field investigations, significant cracks have formed on the ground in front of the Garden Hall (Fig. 8B2, C2). At the Flower Viewing Pavilion, some small paving stones have become loosened, with several transverse cracks observed in the wooden columns (Fig. 8B1, C1).

Many reports have described the paving at the Katsura Imperial Villa as a refined yet fragile form of landscape art. In addition, during the major restoration project of the Showa era (1970s), the Garden Hall was identified as the structure most at risk of collapse and became the first building in Katsura Imperial Villa to undergo complete disassembly and large-scale restoration. In the future, more attention should be paid to the rainy season and the maintenance of stone paving surfaces.

Third, Subsidence at the Shugakuin Imperial Villa may be caused by Groundwater gushing under terrain-dependent garden construction methods.

The Shugakuin Imperial Villa is located at the southwestern foot of Mount Hiei and was constructed between 1656 and 1659 as a hillside estate. It leverages the natural terrain and surrounding expansive rice fields, organizing the upper, middle, and lower villas into a unified landscape composition (Fig. 1d). Among the four gardens, Shugakuin Imperial Villa possessed the most abundant water resources. Situated at the base of Mount Hiei, the villa benefits from year-round groundwater flow throughout the mountainous area. Rainwater and other surface water sources can rapidly percolate through the gravelly sand layers, while deep fractures in the underlying granite bedrock facilitate upward groundwater recharge into the area. The primary source of water for the Goryu Pond in the Upper Villa is two waterfalls diverted from the Otowa River.

Compared to the other three gardens, the area surrounding the Shugakuin Imperial Villa has not heavily impacted by large-scale urbanization73. In contrast, the Katsura Imperial Villa formerly had natural groundwater outflows, but 20th-century urban development and riverbed modifications caused groundwater levels to drop, resulting in the loss of springs such as the Katsura-no-Izumig. Historically, the Kyoto Imperial Palace and Sento Imperial Palace had natural spring outflows; however, due to subway construction and other developments, the groundwater level has declined. Today, the groundwater table in the Imperial Palace area lies ~9 m below the surface, and no spring outflows have been observed.

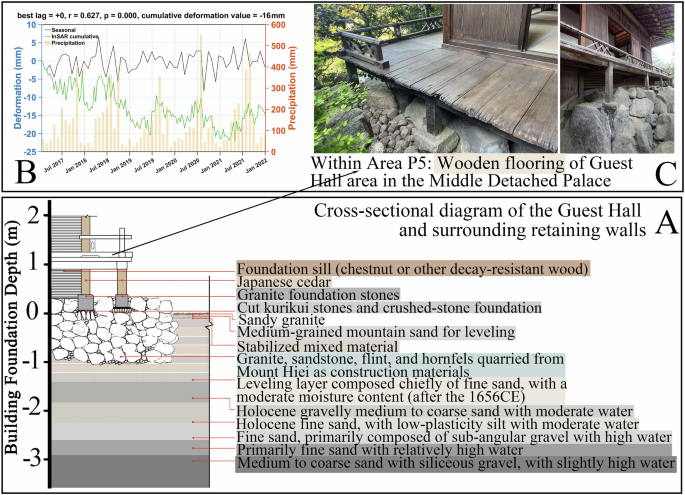

Based on the InSAR descending track detection results, a concentration of subsiding points was identified in the Guest Hall complex of the Middle Villa (P5) (Fig. 5D). Based on the Kyoto Shugakuin Imperial Villa Photographic and Measured Drawings74, along with the 28.9-meter-deep borehole investigation reports75, a cross-sectional diagram of the foundation of the Guest Hall building and the surrounding retaining wall was drawn (Fig. 9A). It was found that beneath the landscape foundation lies a traditional unreinforced stone masonry retaining wall, which makes full use of elevation differences to place Irregularly shaped, naturally occurring blocky stones that have not been artificially cut for scenic effect. The building and courtyard foundations are situated on a bedrock of natural stone. The use of many natural and crushed stone (kuri-ishi) backfills allowed rainwater to infiltrate quickly, preventing water accumulation around the base of the wooden columns. Beneath the artificial foundation layer, the strata are primarily composed of alternating layers of gravelly coarse sand and fine sand (partly interbedded with silt) underlain by a granite bedrock. The highly permeable gravelly coarse sand layers and the relatively less permeable fine sand layers form a differential permeability interface, which may easily give rise to groundwater gushing within the water-abundant environment of the villa27,76. This issue is frequently noted in the repair reports of the Shugakuin Imperial Villa, which highlight that foundational parts of buildings and courtyards are prone to damage due to prolonged disturbance of pore water pressure caused by groundwater.

Fig. 9: Schematic cross-section and deformation analysis within Shugakuin Imperial Villa.

A Schematic cross-section of the foundation of (P5) the Guest Hall building and the surrounding retaining wall. B Time series and STL decomposition60,81 of monthly deformation–precipitation for P5. C Field photographs of P5 area.

The STL analysis results show that the seasonal deformation component at P5 is significantly positively correlated with monthly rainfall and is nearly synchronous (Fig. 9B). This suggests that the drainage and infiltration processes within the stony foundation pads and bedrock fractures beneath the structures are rapid, and that intense rainfall events may trigger surface deformation within a short time through infiltration and pore-pressure changes77,78. Combined with the time series (Fig. 9B), this area exhibits cyclical land subsidence patterns, characterized by uplift during the rainy season as groundwater levels rise and subsidence before and after the rainy season ends. Meanwhile, an InSAR study conducted from 2014 to 2020 across 73 cities in Japan found that many regions exhibited annual cyclical land deformation79,80.

Field investigations revealed that the wooden flooring on the outer side of the Guest Hall has become loose and uneven (Fig. 9C). In the future, management and monitoring of this area should be enhanced during and around the rainy season. Additionally, the Lower Villa underwent repairs work in 2016–2017 due to damage to the revetment caused by groundwater seepage. No significant subsidence has been detected in this area during the InSAR monitoring period. As for the Upper Villa and other areas, the current available monitoring points are relatively scattered (Fig. 6D and 1d).

With respect to the limitations of this study, it should be acknowledged that the parameter settings in this study (limiting the temporal baseline to 60 days and relaxing the coherence threshold to 0.3) improved the overall coherence and spatial density of measurable points but may also reduce the number of interferograms and introduce phase noise from low-coherence noise. This represents one of the study’s methodological limitations, and future work is expected to address this issue through the use of higher-resolution data and other enhancements.

Additionally, PS-InSAR offers advantages over SBAS-InSAR in terms of accurate point identification and is generally able to establish a closer correspondence with GNSS stations. However, within the heritage sites investigated in this study, the number of persistent scatterers was limited, and their spatial distribution was uneven due to vegetation cover and water bodies. Therefore, under improved data acquisition conditions (e.g., TerraSAR-X imagery) and suitable research objectives, the combined use of PS and SBAS methods, together with GNSS observations, represents a promising direction for future improvement, enabling both spatial coverage and high point-level accuracy to be achieved.

Previous InSAR-based studies on world cultural heritage sites such as Myanmar and China19,20,48 speculated that for heritage sites founded on soft soils, annual subsidence rates of 3 mm indicate medium levels of subsidence, often accompanied by cracks that reveal the instability of structural components. For most types of heritage foundations, subsidence rates exceeding 5 mm/yr are considered to reflect abnormal deformation, while rates reaching 10 mm/yr were considered to imply pronounced instability that poses a significant threat to heritage preservation. Under the current management strategy for garden heritage sites, which emphasizes “preservation of the present state with minimal intervention,” most subsiding heritage sites exhibit deformation rates in the range of 2–6 mm/yr. In particular, in areas underlain by soft soils, obvious cracks can be observed, and local measures such as supporting pillars and small steel nails have been installed; no large-scale restoration has been undertaken. Nevertheless, whether a single numerical threshold can clearly define the relationship between annual subsidence rates and structural stability remains uncertain. The severity of damage may vary depending on factors such as foundation conditions and the cumulative duration of subsidence and thus requires further investigation in future studies.

In terms of data, since groundwater data in most regions of Japan are confidential and not publicly available, and relevant exploration data are also lacking, this study was unable to further elaborate on the related conclusions using such data. It is hoped that future research will provide more in-depth explanations as more information becomes accessible.

In conclusion, first, this study employed multi-track InSAR data integration and remote sensing technique to monitor deformation and detect land subsidence spatial characteristics within four representative imperial gardens in Kyoto. The research results confirm existing knowledge and are supported by the data. The study aims to explore the driving factors of land subsidence in Kyoto imperial garden heritage sites under historical landscape construction practices. The results indicate that subsidence may occur under the foundation construction methods of Kyoto palace buildings and white sand courtyard due to their foundation on Holocene sedimentary environments that have been repeatedly altered through generations of artificial filling. Subsidence may be triggered by the presence of thick Holocene deposits under lake excavation, hill piling, and stone masonry construction techniques; and in terrain-dependent garden designs, subsidence may be triggered by interference from underground water. The complex interplay between human historical activity and natural geographical conditions has shaped the construction methods and unique landscape heritage of gardens. As the landscape heritage evolves over time and outer hydrological conditions change, landscape heritage may be affected by the construction methods and geographical soil settings, and land subsidence may occur in this area.

Second, within a broader international context, subsidence phenomena have also been observed in other World Heritage gardens, such as the Summer Palace and Villa d’Este. These heritage sites are situated on shallow foundations and Holocene sedimentary units, where the long-term interplay of anthropogenic activities and natural factors makes localized ground instability likely to occur. Although the hydrogeological conditions differ across regions, preventive subsidence monitoring has become a shared necessity for heritage conservation.

Third, for the royal heritage sites examined in this study, efforts should focus on strengthening management and preventive protection during the rainy season. It is necessary to promptly repair ground fissures and extensive cracking in wooden columns to prevent further aggravation of structural instability.

AloJapan.com