The Japanese authorities are back at it. A new prime minister and finance minister are huffing and puffing about yen weakness and jawboning markets – including with threats to intervene. We’ve seen this movie before, and the new team seems even more confusing than its predecessors.

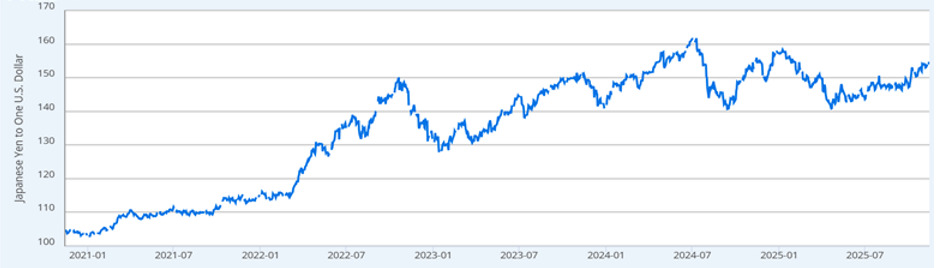

The yen is undeniably weak. Against the dollar, it has fallen by more than 30% over the last five years (Figure 1) and some 7-8% since it became clear that Sanae Takaichi would become prime minister in October 2025. The real yen has also depreciated some 30% over this period.

Figure 1. Yen’s depreciation against the dollar

Japanese yen to dollar spot exchange rate

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Policy incoherence

When I started my US Treasury career eons ago in the Foreign Exchange Office, the dollar was then under siege due to a crisis in confidence in US policy-making. We were intervening daily to support the dollar, even though it went down every day. Reflecting my youthful naïveté, I asked my boss why the US didn’t adjust its macro policies instead of unsuccessfully intervening. He looked at me a bit dumbfounded – the administration can’t fix fiscal policy, the Fed isn’t moving on monetary policy. ‘We’ have to be seen as doing something, so we’re intervening.

Japan’s ministry of finance zealously guards its responsibility for the Japanese yen, even if monetary policy is perhaps the key determinant for currency values and under the domain of the ‘independent’ Bank of Japan.

The MoF’s attitudes towards the weak yen may border on incoherent. A weak yen is good for exports, even though exports are less important to Japanese industry given its multinational reach. But Japanese citizens are unhappy with the inflationary consequences. After yearslong efforts by Japan’s authorities to fight deflation, Japan’s inflation is roughly 3% and appears solidly above the 2% target. Citizens also see a weak yen as limiting real incomes. The MoF knows all of this.

A weak yen is a political hot potato. But Japan’s policy mix doesn’t add up.

A weak yen is perhaps inevitable given low interest rates and the so-called carry trade. The BoJ has lifted its benchmark rate from -0.1% to 0.5% over the last year, and stepped back so far from moving higher, notwithstanding heated debate. Japan has embarked on modest quantitative tightening. Japan’s benchmark and highly watched 10-year yield has risen a percentage point over the last year to around 1.75% but remains well below inflation, as do the shorter parts of the yield curve.

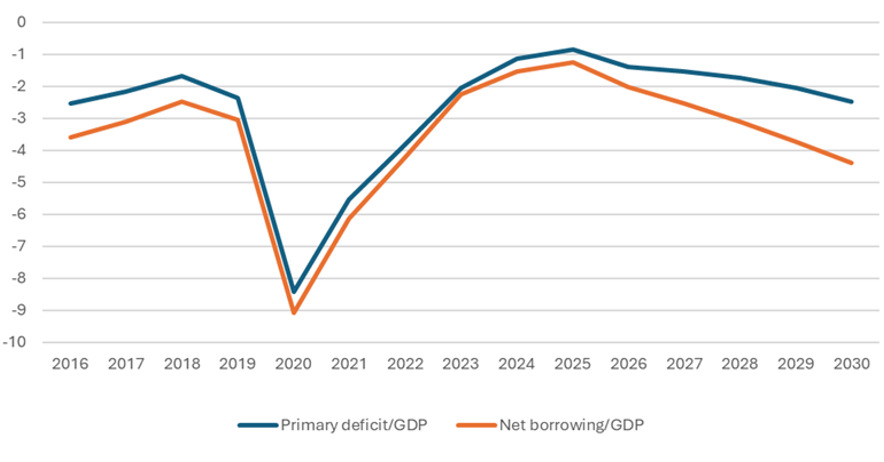

Japanese government debt is enormous – circa 230% of gross domestic product. The outlook is for continued considerable primary and overall deficits, though the inflation tax is limiting the impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio much to the MoF’s delight.

Figure 2. Deficits projected to continue

Japan’s primary and overall deficit/GDP

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook Database, October 2025

Against this background, Prime Minister Takaichi has proposed a fiscal expansion, exceeding the caution of her predecessors and the relative ‘conservatism’ of the MoF mandarins. The MoF’s original economic package of ¥17tn was reportedly deemed weak by Takaichi and the administration then added another ¥4tn. While it is difficult to disentangle double counting from the stimulative impact of Japanese fiscal policy packages, some analysts expect the stimulus from the Cabinet-approved version of the package to raise 2026 GDP from around 0.5% to 1%.

One would expect such a fiscal expansion to put upward pressure on interest rates and thus boost the yen’s value. While the 10-year Japanese government bond yield is up some 20 basis points since October 2025, the yen has not strengthened – even though interest differentials have narrowed against the dollar at the same time.

That is in part because markets appear to be somewhat concerned about the direction and sustainability of Japanese fiscal policy. Meanwhile, a divided BoJ, which has been reluctant to lift official rates, is again debating whether to hike at its upcoming meeting later this month. While inflation, a weak yen and real data may support a hike, further hesitancy may persist in the shadow of the political realities of the Diet’s consideration of the Cabinet’s fiscal proposal. Additionally, the BoJ isn’t as independent as the European Central Bank or the Fed, and well understands the fiscal consequences for Japan’s public accounts of raising rates to address current inflation. Many analysts believe the BoJ is impacted by fiscal dominance.

What does this mean for currency policy?

Like the US Treasury earlier in my career, the MoF feels it has to do something. Rather than Japan confronting its policy mix, the finance minister jawbones about the weak yen, threatens intervention and decries that markets are one-sided, disorderly and not reflecting underlying fundamentals. But while significant short positions may occasionally build up, trading in yen is not disorderly – business is getting done, liquidity is good and bid/offer spreads are narrow. Rather, markets are reflecting fundamentals and voting on Japanese economic policy.

Ultimately, the weak yen in significant part reflects Japanese policy incoherence. So does Japanese – and its finance ministry’s – foreign exchange policy.

Mark Sobel is US Chair at OMFIF.

Interested in this topic? Subscribe to OMFIF’s newsletter for more.

AloJapan.com