With the number of bear attacks on the rise in Japan, expert Ohnishi Naoki believes it is necessary to do more to keep the country’s bear population under control, including training and hiring hunters.

Bears Entering Residential Spaces

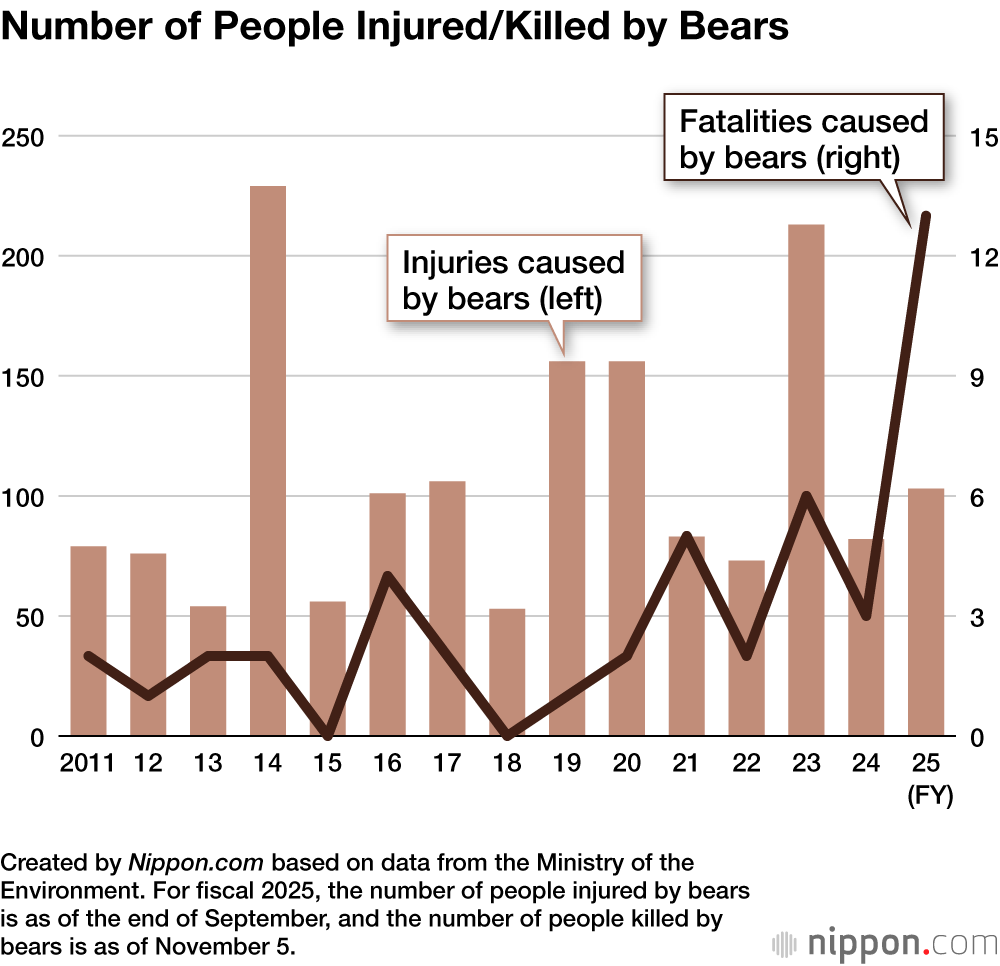

A surge in bear sightings and attacks on people has shaken Japan, with the northern prefectures of Tōhoku particularly affected. Ohnishi Naoki of the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute’s Tōhoku branch judges that the situation is at disaster level with urgent action required.

“Previously, humans mostly encountered bears in satoyama areas [spaces where people and nature coexist],” he says. Now, these encounters are breaching into suburban residential areas and even downtown areas of prefectural capitals. The trend first became apparent in 2023, but this year the bears are moving deeper into human living spaces.

“In Morioka, bears have been spotted in the parking lot of the Bank of Iwate’s headquarters as well as the grounds of Iwate University. In Akita Prefecture, bear sightings have been reported near supermarkets and high schools.

“There has also been a serious level of bear attacks this year, and I think the deaths and injuries these have caused makes the situation comparable to disasters like tsunamis and heavy rain.”

As the range of bear sightings has expanded, in Akita Prefecture the Ground Self-Defense Force has even been deployed. Ohnishi says that one factor behind increased sightings is the rise of “urban bears.” He says, “These are bears born and raised near areas where humans live and they take the existence of humans for granted. They now move in and out of populated areas on a daily basis.

“These bears know about the existence of humans from a young age, and have learned to tolerate them to some extent. Bears don’t want to have to encounter humans, but through experience they’ve developed a sense that they can get away with entering residential areas at night, and that they aren’t likely to be discovered during the day if they’re up in the trees. As a result, they’re gradually venturing deeper into the areas where humans live.”

Lack of Food Driving Bears Closer to People

A shortage of acorns and other nuts that bears usually eat is another factor in the rise in bear sightings. “In autumn, bears eat heavily to prepare for winter hibernation,” Ohnishi explains, saying that this is not because their stomachs are empty, but because the part of their brains that tells them they are full is switched off. “In years when the mountains produce fewer nuts, bears expand their range of activity in search of food and end up venturing into human living spaces. There were relatively few bear sightings in 2021 and 2022, but in 2023, when nut production was poor, more bears entered human-populated areas. They’re attracted by persimmons, chestnuts, household garbage, and pet food. Encounters are increasing, pushing up the risk of attacks.”

Regarding stories about them eating human flesh, Ohnishi says, “It’s true that there have been reports of bears eating human corpses. But bears almost never attack humans for the purpose of eating them. Most attacks happen when a bear runs into a human and strikes out in self-defense before running away. In rare cases, a bear may taste human flesh from a corpse and learn that people are edible.”

Population Changes Among Humans and Bears

Ohnishi notes how changes in human living environments are also having an effect. “As the human population declines and ages, fewer people visit the satoyama areas, leaving fewer eyes to keep watch. Overgrown grass, bushes, and trees in empty lots and vacant houses provide cover as well as food for bears, and the persimmon and chestnut trees left behind by people are also attracting them.

A mother bear and her cubs eating chestnuts near houses at a town at the foot of the Ōu Mountains in Iwate Prefecture in October 2023. (© Satō Yoshihiro)

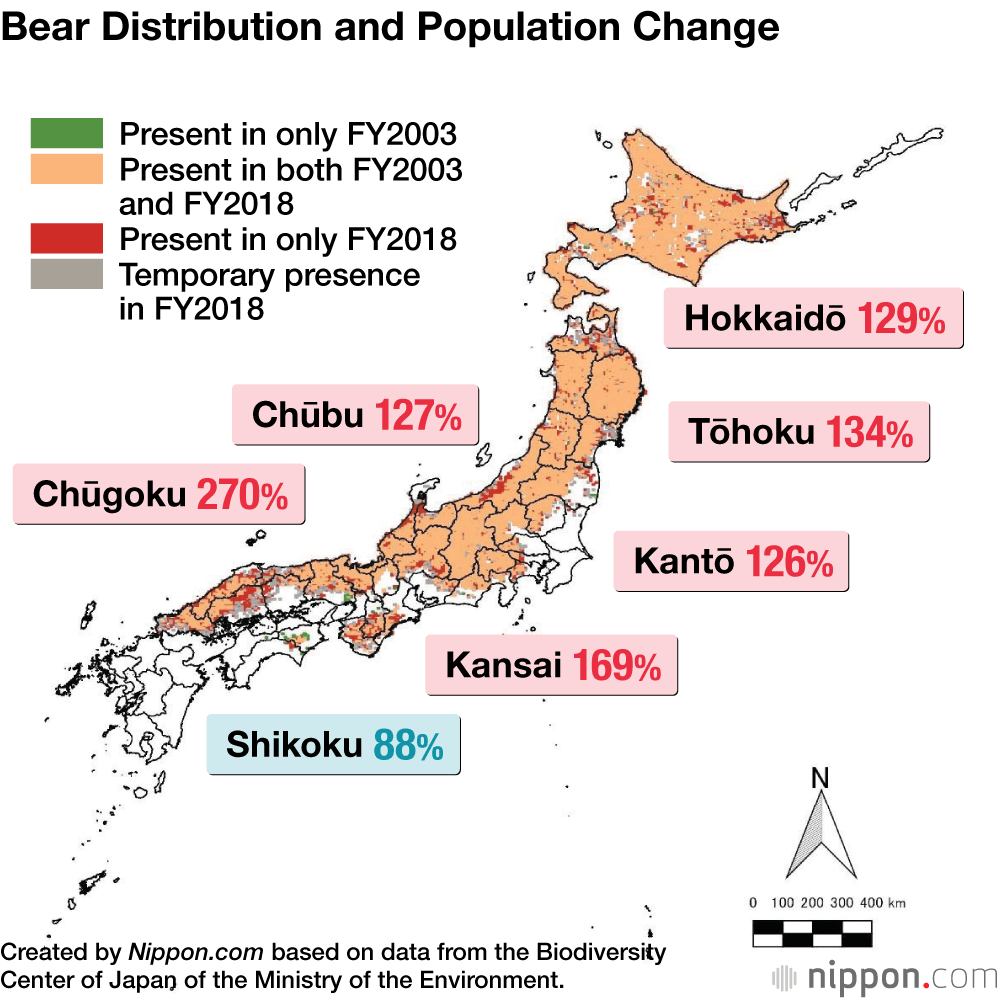

“The rise in bear-related casualties is fundamentally the result of an increasing bear population. In Akita Prefecture, even though more than 2,000 were culled in 2023, bears continue to emerge from the mountains. This is because their numbers are growing and the population is overflowing.”

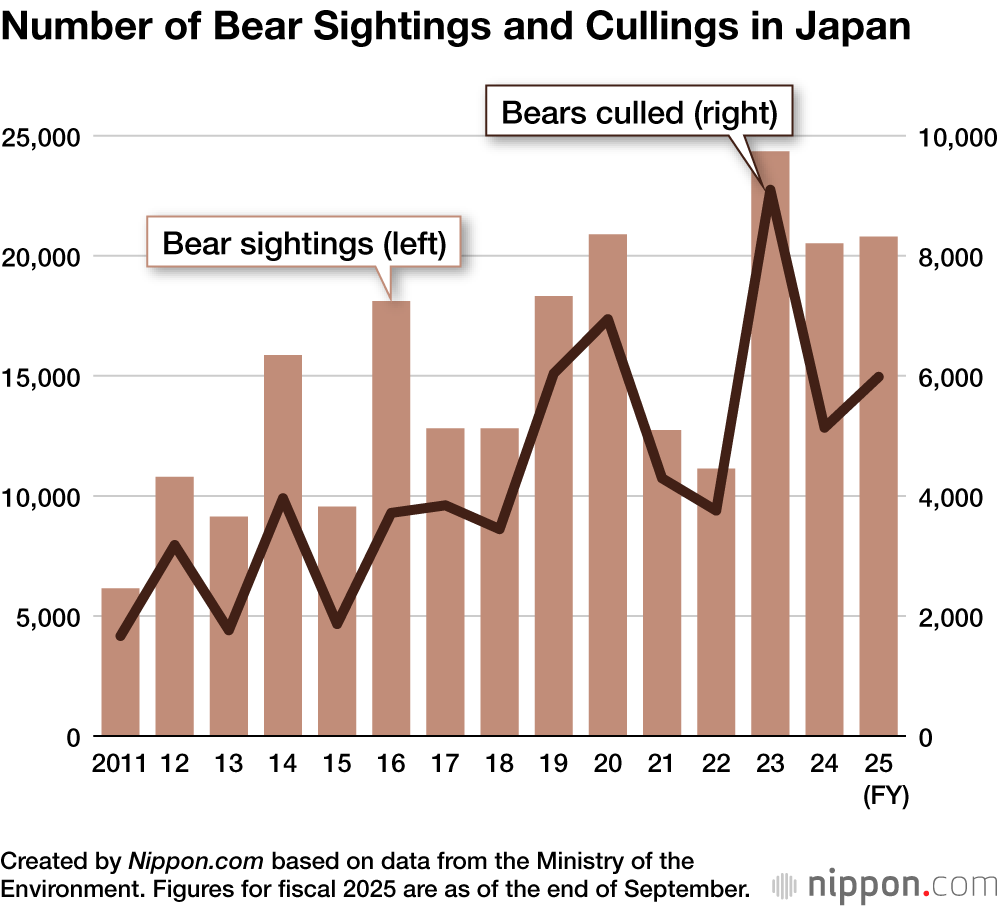

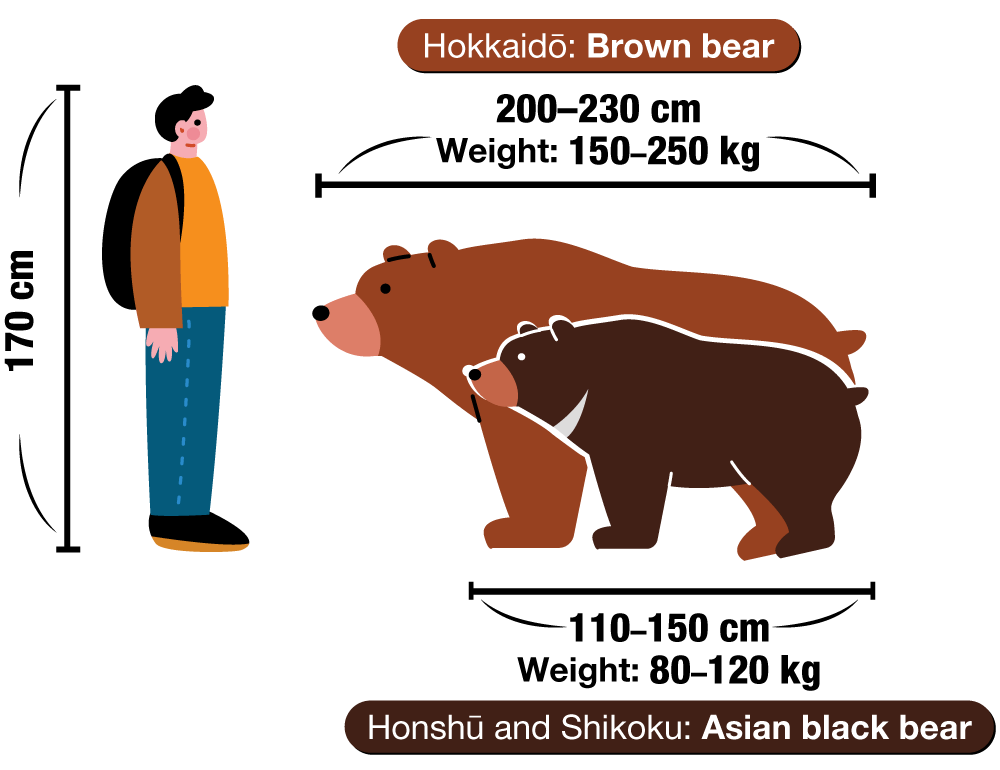

According to the latest data from the Ministry of the Environment, there are about 12,000 brown bears in Hokkaidō and 42,000 Asian black bears in Honshū and Shikoku. Overall, the population trend is upward; for example, there were 633 bears in Miyagi Prefecture in fiscal 2008 and 2,783 in fiscal 2024. A total of 9,099 bears were culled in fiscal 2023, and 5,136 in fiscal 2024.

“One reason for the increase is that Japan’s approach towards bears for many years was to protect them,” Ohnishi says. “Hunters refrained from shooting them or caught them with traps. When captured, bears were sometimes released in remote mountains rather than killed. These preservation efforts appear to have contributed to the rise in the bear population.”

More Action Needed

Ohnishi believes more needs to be done. “As I’ve said, this year’s bear situation has reached disaster levels. In the short term, I support combining local government and hunting association efforts with Self-Defense Force assistance. Police should also use rifles, and municipalities should employ ‘government hunters’ [municipal employees specializing in hunting].

“However, simply culling the bears that spill out of the mountains won’t solve the issue. In the medium to long term, we’ll have to go into the mountains and actively reduce the bear population.

“The 2014 amendment to the Wildlife Protection, Control, and Hunting Management Act added “population management” as an objective in addition to “protection.” In 2024, all bears outside Shikoku were designated for population control. Prefectures now receive subsidies for this, so they should make good use of the funds.

“It’s also important to make changes to local environments that reduce the risk of bear encounters. Bears are attracted to vacant lots with overgrown weeds or persimmon and chestnut trees. In areas between residential and forest zones, removing brush and undergrowth is essential to reduce hiding spots. Municipalities and local organizations should take the lead in organizing these efforts.

“Trash may serve as food for bears, so garbage should be put out in the morning instead of at night and kept in enclosed areas. Pet food and kerosene should also be stored indoors and sealed.”

Japanese cabinet ministers discussed the issue of bears in a special meeting on October 30. Ohnishi thinks that there are a number of things the government could do. “The biggest problem is a shortage of personnel. Hunters are aging, and their numbers are declining. It’s necessary to train younger hunters and also for local governments to hire “government hunters” as public officials. However, it takes about 10 years to train people to use rifles, so the shortage won’t be fixed quickly.

“Members of hunting associations are private citizens, many of whom have other jobs, so it’s not appropriate to rely on them for public safety. In urban areas, where public safety is critical, the police force, which can handle rifles, should take the lead in bear control. On the other hand, for medium- to long-term measures, such as reducing bear numbers in the mountains, hunter associations are better suited to help. Bear management should be handled through proper division of roles.

“The government should make bear control a permanent, systemic measure, not just a short-term response, as “government hunters” cannot be rotated like other public officials when employed.”

A bear and her cubs crossing a street at the foot of the Kitakami Mountains in Iwate Prefecture in July 2018. (© Satō Yoshihiro)

Stay Calm and Keep Distance

According to Ohnishi, avoiding encounters in the first place is an important aspect of self-protection. “When walking in mountains or semi-wild areas where bears may be present, wear a bell or play a radio so they know you’re around. That’s the basic rule. Bears don’t want to encounter humans either, so in most cases they’ll avoid you if they hear you.”

“But if you do meet one,” he says, “Don’t panic and run. Turning your back may cause the bear to follow you. Instead, slowly step backward to make distance. If you have bear spray, use it calmly while facing the bear. If you’re about to be attacked, lie face down on the ground and protect the back of your neck with both hands.

“We’re now in an age where people and bears live in close proximity, which means we must stay mindful in our daily lives. I think that all we can do is to steadily implement these three measures: reduce the bear population, create an environment that doesn’t attract bears, and remain vigilant.”

(Originally written in Japanese based on an interview by Matsumoto Sōichi of Nippon.com and published on November 11, 2025. Banner photo: A bear on the grounds of the Hara-Kei Memorial Museum in Morioka in October 2025. © Kyōdō.)

AloJapan.com