On our recent road trip around Japan, my husband Brent and I stayed in one of Japan’s famous — or infamous? — “love hotels.”

That is, the places where some Japanese go for sexual encounters. They have a pretty fascinating history, and unlike in most Western countries, they’re not considered “sleazy.”

We were just looking for a place to stay for the night, and the price of a room was a bargain: $54 USD.

(It’s a fairly well-known travel hack in Japan that the prices at these establishments are cheaper than at other hotels — in part, because they make money renting “by the hour.”)

The room and bed were huge — far larger than any other we’d had in Asia. And the decor was interesting: 80s-era funk?

The room included little lidded boxes filled with condoms, lube, and even a vibrator —thankfully, with a plastic wrapping that is presumably replaced after each guest.

There was also one item we didn’t expect to find.

When it comes to sex, what is plastic wrap used for anyway? We asked our heterosexual traveling companions, and they didn’t know either.

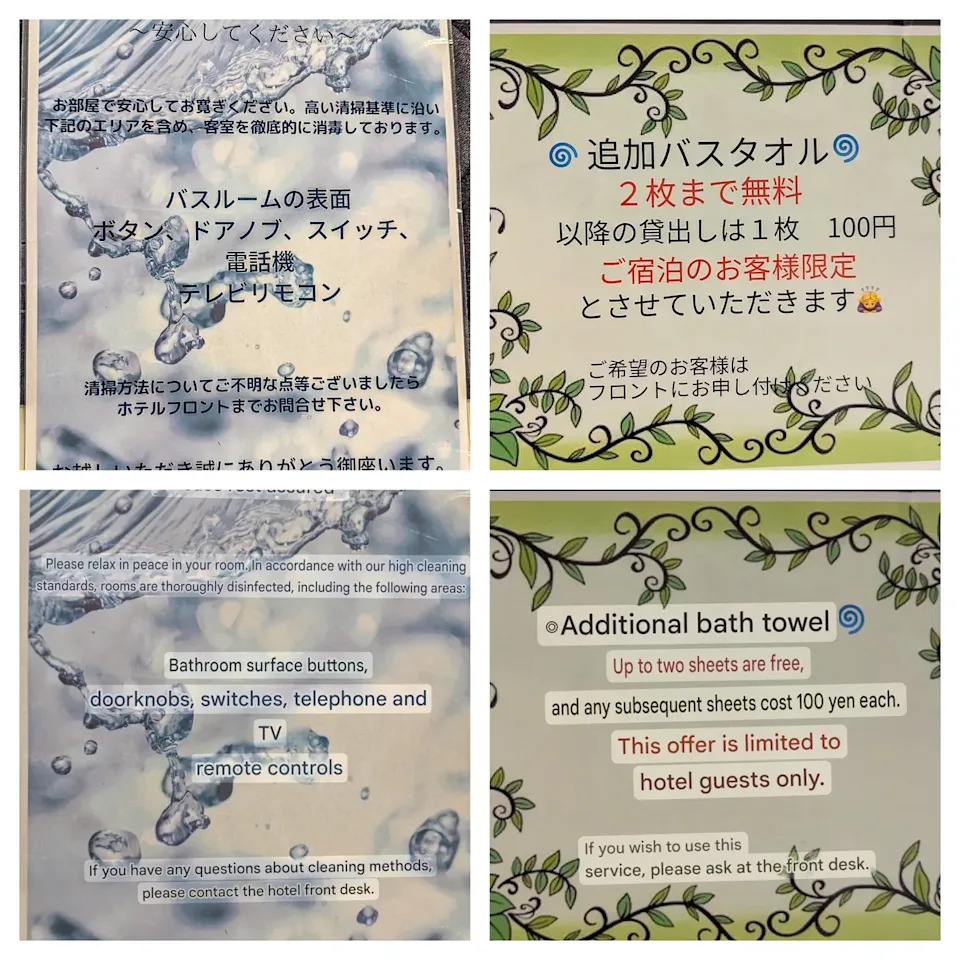

There were other reminders that this wasn’t your regular hotel, including two placards left on the bed assuring us the room had been thoroughly sanitized.

Even — as you can see from the sign below — the doorknobs:

The room definitely smelled sanitized, but that only reminded me why it needed to be so sanitized.

On the other hand, it was almost certainly the cleanest hotel room we’ve ever stayed in.

What are Japanese “love hotels” all about anyway?

The first mention of such establishments in Japan dates to the Edo Period in the 17th century, when secret doorways provided discreet ways to enter inns and teahouses where more than tea was on the menu.

The actual term “love hotel” may have originated in Osaka in the late 1960s, when a hotel named “Hotel Love” opened — but accounts vary, and no one really knows for sure.

We do know that the period after World War II was a time of great upheaval in Japan.

The country faced a severe housing crisis due to the devastating air raids on Tokyo and other cities. This forced multigenerational families to live together in tiny apartments where privacy was hard to come by; many Japanese residences have thin or even paper walls. Then there were the half a million American soldiers stationed around the country.

Prostitution was outlawed in 1956. And with half a million horny American soldiers, and all these Japanese people looking for privacy, something had to give.

Enter love hotels, then known as “tsurekomi inns,” or “bring along” place — a place where a man would “bring” a woman, whether his girlfriend, wife, or paid companion.

The authorities mostly ignored these establishments, creating a kind of legal loophole for prostitution.

Over time, “love hotels” became a well-known part of Japanese culture: a way for married couples to get some much-needed privacy, an outlet for amorous young people, and a discreet way for men to have affairs.

Japan’s housing crisis slowly eased, and by the 1970s, fewer married couples frequented love hotels, which became primarily advertised in sex magazines for men. At this point, they acquired a more seedy reputation.

The industry eventually changed course by cleaning up its act — literally, in the case of our room! — marketing its offerings to women. That included adding amenities like jacuzzi tubs, beauty treatments, and gourmet meals.

Some hotel owners even introduced “themed” hotels to distinguish themselves from the competition.

The Meguro Emperor, built in 1973 to resemble a castle, was reportedly the first such love hotel — and it’s still open today (and even listed on Booking.com, which also has a category for love hotels). Other love hotels resembled UFOS or had, say, a Balinese island theme.

These days, an over-the-top theme or garish exterior often signals that a place is a love hotel.

Over the years, other amenities were also added: mirrored ceilings, rotating beds, and even karaoke machines.

Japanese attitudes about sex are extremely complicated — and, often, seemingly contradictory — but a Japanese friend tells us that a man hitting on a Japanese woman in a bar would be a major breach of protocol. But a Japanese woman suggesting to a man that they visit a nearby love hotel is both acceptable — and common.

A 2013 study estimated that 90% of the time, women choose the hotel and room.

All this said, Japan’s love hotels may be past their heyday — a victim of changing social attitudes, behavior, and demographics. More Japanese are living in their own apartments now, and the country’s population is aging — and the number of Japanese are falling.

Younger generations are forgoing having children entirely, and even sex itself is declining in popularity, with one in four Japanese remaining virgins into their thirties.

At their height, there may have been more than 30,000 love hotels; today, the number could be as low as 5,100.

Which brings us back to Brent’s and my experience at the Belfus Hotel in Koriyama, Japan.

Generally, couples either stay for a few hours (called “rest”) or overnight (called “stays”). Prices range from $16 to $120, depending on the length of stay and location.

We’d booked online and weren’t sure it was a love hotel — until we arrived and saw a sign in the parking lot advertising the rates.

Yes, they rent by the hour, and the earlier you check in, the cheaper it is.

Cheaper by the hour!

(Michael Jensen)

The check-in process was also unusual. The very premise of a love hotel is discretion, and the front desk clerk was mostly hidden from view behind a small window.

It felt like sneaking into a speakeasy during Prohibition back in 1930s America.

Most Japanese hotel clerks verify that your face matches the photo in your passport, and I crouched down to the narrow opening to pass my passport to the clerk.

But no — that was a major faux pas. The desk clerk emphatically did not want to see our faces. Our passports were ignored. A hand hastily thrust our keys toward us, along with written instructions in English on how to order breakfast.

We headed for our rooms. But first, we perused the items on display in the lobby designed to, er, enhance our stay. That included a variety of colored powders for the bathtub, as well as lotions, soaps, and creams.

In the hallway on the way to our room, lights above each doorway indicated whether a room was occupied. Green meant unoccupied, red — well, someone was getting busy.

Inside each room, there is an enclosed foyer with another door into the main room.

The design is so that if food or drinks are ordered — via a screen on your television — they can be delivered without any human interaction.

Our room came with two free drinks, along with breakfast the following morning. Each time, they were delivered discreetly by a hotel employee who rang a chime, then entered with their own key, placed the items on a fold-out tray in the foyer, and left again, sounding a bell to indicate that all was clear.

Meanwhile, the bathroom was enormous, larger than some hotel rooms we’ve stayed in. And it had pretty much everything you might need.

I was curious whether the Belfus was LGBTQ-friendly, so I scanned the “adult” movie listings.

It was all very heterosexual. A few love hotels in Tokyo and Osaka now market themselves as LGBTQ-friendly, and most places probably wouldn’t turn same-sex couples away — possibly because discretion is so important that they may not realize the gender of those involved.

I appreciated the hotel’s low price, and I definitely enjoyed the novelty.

And the free drinks helped me relax a bit — even stop thinking about exactly why the doorknobs had needed to be so thoroughly sanitized.

As for what happened after that, well, what happens in a Japanese love hotel stays in a Japanese love hotel.

AloJapan.com