More than thirty years ago, as an academic visiting Sapporo University, I was struck by a Japan where discipline and innovation seemed woven into everyday life — a culture in which Aristotelian prudence (phronesis) guided both social norms and decision-making. That experience has stayed with me, shaping my reflections as an economist on national policy choices.

Today, Japan again offers a lesson in measured wisdom: under its new Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who took office on 21 October 2025 and is the first woman to serve as either president of the Liberal Democratic Party or prime minister, the Japanese government is investing in growth and innovation rather than rushing to cut debt. With vast public assets and deep domestic savings, Japan’s challenge is not debt itself, but on how prudence can sustain progress.

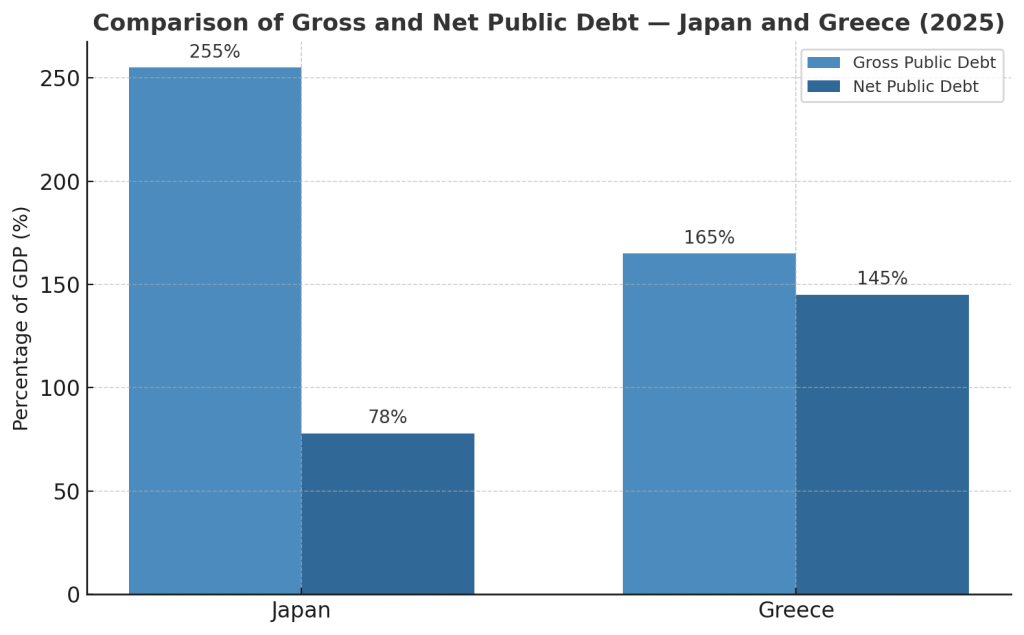

A comparison with Greece is revealing. Both nations have carried debt levels exceeding the size of their economies, yet their outcomes diverged sharply. Japan’s stability contrasts with Greece’s past crises and austerity. The difference lies less in numbers than in the ethos guiding them — what Aristotle called phronesis, or practical wisdom.

As explored in the recent book Aristotle in Japan: Reception, Interpretation and Application (Kondo & Tachibana, 2022), Japanese thought has long absorbed Aristotelian ideas of virtue, prudence, and balance, blending them with a native ethic of harmony and responsibility. It is this living prudence that helps Japan turn debt into stability rather than disorder.

Seeing Beyond the Numbers

As illustrated in Figure 1 Japan’s public debt exceeds 250 % of GDP — seemingly alarming. Yet when public assets such as pension funds, postal savings, and foreign reserves are included, its net debt drops to about 78 % of GDP (IMF Fiscal Monitor, 2025). Greece’s net debt remains close to its gross level, not because public assets are absent, but because comprehensive financial asset data are limited and fragmented across institutions. The available evidence suggests that the value of these assets only modestly offsets total liabilities. The essence, however, beyond the size of the net public debt, also lies in the quality of the assets, as well as in the level of trust that accompanies the overall management of the state budget.

Figure 1. Comparative gross and net public debt for Japan and Greece (2025)

This contrast highlights how asset composition and institutional trust, not just debt magnitude, determine fiscal resilience. From a tax perspective, the divergence extends further. While Greece collects a larger share of its GDP in taxes than Japan, it does so under greater fiscal strain. Greece relies heavily on consumption and indirect taxes to service its obligations, reflecting a structure that prioritizes revenue over growth. Japan, by contrast, combines moderate taxation with extensive public savings and productive investment, reinforcing trust and long-term stability. (Sources: OECD, Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2025: Japan; IMF, World Revenue Longitudinal Database)

Japan’s position resembles that of a well-managed household — heavily mortgaged, yet owning productive assets and enjoying trust from its lenders, who are largely its own citizens and institutions. Greece’s earlier crisis, by contrast, reflected a household living on credit rather than capital. When external funds dried up, the imbalance between debt and productivity became clear, forcing austerity and social strain — a deviation, in Aristotelian terms, from the golden mean.

Οἰκονομία — The Art of the Household

The very word economy (οἰκονομία) comes from oikos (household) and nomos (management). It reminds us that a nation’s economy, like a household, must balance means and ends through prudence and foresight. It is as if the Japanese government acts as the overarching household (νοικοκυριό) of the nation — managing resources responsibly and leading by example.

This prudence extends to Japanese families themselves: high savings, cautious investment, and a focus on long-term stability mirror the government’s ethos. Greek households, on the other hand, often reflect the vulnerabilities of the state — low savings, reliance on credit, and sensitivity to external shocks. Measured through οἰκονομία in its truest sense — stewardship of the household — Japan again embodies phronesis: the quiet virtue of balance.

Debt, Assets, and the Return on Wisdom

Japan’s case shows that public debt can be virtuous when guided by prudence. The return on Japan’s public assets — from infrastructure to innovation — likely exceeds the cost of its borrowings. Investments in green technology, robotics, and high-speed rail generate social and economic returns far beyond bond yields. This alignment of moral and fiscal reasoning reflects Aristotle’s golden mean: debt becomes sustainable when it serves balance rather than excess.

As Kondo and Tachibana (2022) note, Japanese interpretations of Aristotle root ethics in practical governance — where wisdom is expressed not through austerity, but through foresight and moderation.

Conclusion: Aristotle’s Legacy in Two Economies

Prime Minister Takaichi’s agenda continues Japan’s tradition of phronesis in action: investing responsibly, ensuring debt grows slower than the economy, and keeping policy grounded in trust and prudence (Reuters, 2025). Greece, meanwhile, remains a reminder that fiscal imbalance often reflects a deeper ethical imbalance — a loss of moderation and foresight.

Japan and Greece thus represent two moral economies of debt: one built on phronesis, the other on necessity. The Aristotelian lesson endures — sustainability depends not on numbers, but on wisdom.

In this light, Japan resembles not an indebted nation but a prudent household—one that offsets its obligations with enduring assets and is guided by the timeless virtue of phronesis, or practical wisdom.

*Dr Steve Bakalis is an economist with interests in political economy, social justice, and public administration, having collaborated with La Trobe University, the University of Melbourne, Victoria University, and universities in the Asia-Pacific region and the Arabian Gulf.

AloJapan.com