Fermented foods are gaining attention as healthy, nutritious additions to the diet. Nattō comes with a strong smell, but is hard to beat as an ingredient bringing benefits to those who enjoy it. A look at some ways to consume these pungent beans.

Nattō, soybeans fermented with the nattōkin bacteria, are a favorite food for many Japanese, but disliked due to their strong scent by plenty of people. For a deeper look at this dish, have a look at “Nattō: Japan’s Sticky, Pungent, and Highly Divisive Fermented Food” and in our Japan Glances feature on them; read on below for some ways they are commonly enjoyed in Japan.

Nattō Gohan

For this simple and delicious dish, just mix together a store-bought pack of nattō with the tare sauce and mustard that comes with it and then pour it over piping hot rice. Regular accompanying condiments include chopped green onions, grated ginger, and aonori seaweed. Adding a splash of mayonnaise, vinegar, or sesame oil varies the flavor. People also like to combine it with kimchi or a raw egg. In some Northern Japan regions, sugar is added.

Nattō Chāhan

The secret to this egg-fried rice dish with nattō is to stir-fry all the ingredients together until the nattō loses its stickiness.

(© Pixta)

Nattō Maki

This sushi roll with its filling of nattō is comparable to kappamaki, or cucumber roll, for being reasonably priced. It is widely available at supermarkets and convenience stores, and can be ordered at just about any sushi shop as well.

(© Pixta)

Nebaneba-don

This nebaneba, or “sticky,” rice bowl dish combines nattō with other viscous foods like okra, yamaimo, and mekabu, creating a hearty meal, rich in dietary fiber.

(© Pixta)

Nattō Soba, Udon, and More

Nattō goes great with many other staples, not just rice! Add to soba, udon, pasta, and mochi, along with your favorite condiments as a topping.

Nattō pasta. (© Pixta)

Nattō Kitsune

For this dish, pockets of deep-fried abura-age tōfu are opened up, stuffed with nattō, and then grilled. This combination of two different soy products makes it a great side dish or snack.

(© Pixta)

Nattō has been adapted to a wide range of modern eating habits, such as nattō omelet, nattō curry, and nattō on toast. But here are some more traditional dishes.

Nattō Jiru

In Akita and Yamagata Prefectures, it is traditional to serve nattō by mashing it and adding it to miso soup to create this hearty version. An easier option is to use hikiwari nattō or regular nattō, which still gives plenty of flavor.

Nattō jiru from Akita Prefecture. (Courtesy the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries)

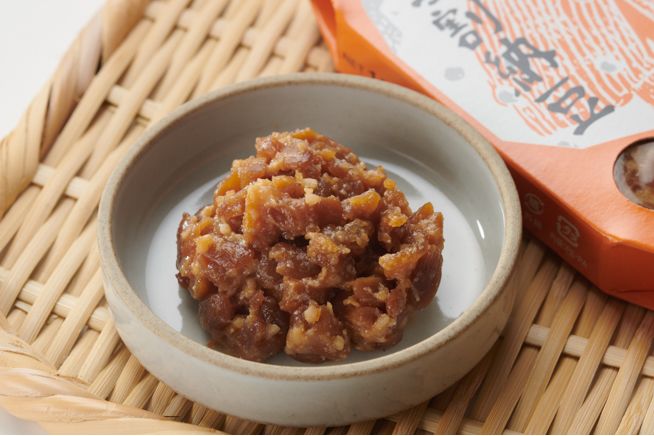

Goto Nattō

This is a local Yamagata Prefecture dish, made by adding salt and rice kōji to hikiwari nattō and letting it ferment for a second time. It is similar in appearance and saltiness to miso. It is also known as yukiwari nattō or kōji nattō.

Yukiwari nattō from Yamagata Prefecture. (Courtesy the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries)

Soboro Nattō

This dish comes from Ibaraki Prefecture, a major nattō production area, and uses nattō that has poor stringiness, salted together with kiriboshi daikon dried radish strips. It is a traditional preserved local dish that still appears on dining tables today. The word soboro, meaning “crumbled” or “ground,” is sometimes pronounced shoboro.

Soboro nattō from Ibaraki Prefecture (Courtesy the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries)

Incidentally, there is a Japanese sweet called amanattō, made by boiling beans in a sweet sauce and then drying them. It is so called because it resembles shiokara nattō, a type of nattō fermented with kōji mold. You may be relieved to know, though, that unlike nattō, it has no smell and is not sticky.

Despite sharing a name, the sweet treat amanattō has nothing to do with its fermented soybean namesake. (© Pixta)

(Originally published in Japanese. Text by Ecraft. Banner photo: Nattō gohan. © Pixta.)

AloJapan.com