11:06 JST, October 11, 2025

KYOTO — The swish of brush strokes filled the quiet workshop, reminiscent of a rustling dress. Artisan Satoshi Furuhashi was applying liquid dye to a cloth with a deer-hair brush. Sometimes he would use a different side of the brush, flipping it around.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The Yomiuri Shimbun

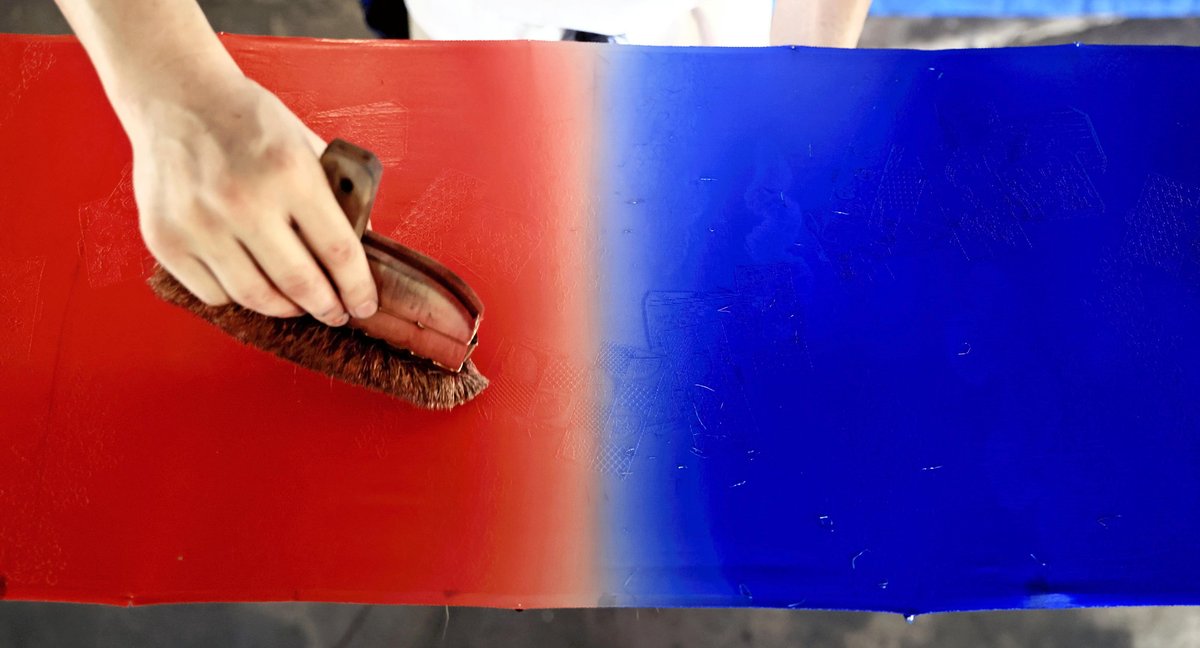

Brush dyeing artisan Satoshi Furuhashi applies red and blue dyes to a cloth, leaving a white space in between, in Minami Ward, Kyoto.

Furuhashi, 49, conducts his craft at a workshop run by Furuhashi Senko, a dyeing company in Minami Ward, Kyoto, founded by his father.

The workshop is on the first floor of a boxy building with roughly 330 square meters of open space that stretches more than 20 meters deep without interruption.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Furuhashi uses the bokashi technique to blur the border between red and blue dyes while leaving a narrow strip of white in between.

To prevent drafts, which can cause uneven dyeing, the windows remain closed and the air conditioning off. Temperatures exceed 40 C in summer and drop below zero in the winter.

In the still air, Furuhashi stood in front of a silk tanmono, a long piece of cloth used to make kimono, that was suspended across the workshop. He was steadying his breathing before starting to dye the piece.

His signature bokashi technique is a marvel. It employs gradations of color, intensity and tone by applying colors next to each other while keeping them distinct, as any mixing would dull the colors and turn them blackish.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The workshop uses more than 100 brushes of various sizes, employed according to dye color and intensity.

On the day I visited, Furuhashi left the cloth an undyed white between sections of red and indigo, and then created gradations of color in the middle ground by spraying mist from a spray bottle. I watched the white gradually disappear, the colors blending beautifully like a ridgeline at sunset.

“You can be taught the angles to apply the brush, but you have to learn the pressure to apply by yourself,” Furuhashi said. “You need experience and intuition. And you need to understand the cloth.”

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Strips of tanmono cloth are fixed to Japanese cedar pillars and stretched out.

“If the colors mix, they become dull,” he added. “If they aren’t close to each other, there’s white space. It’s hard to get it just right.”

It took 10 years for Furuhashi to learn how to create a smooth gradation. He also mastered many other techniques, such as toyama bokashi, for depicting mountains in gradation, and maki bokashi, for creating color gradations around patterns.

Furuhashi was assigned to dye battle robes and yukata summer kimono for NHK’s Taiga historical dramas. In 2015, he was recognized as an up-and-coming craftsperson with advanced Kyo-yuzen dyeing skills by Kyoto Prefecture.

His father and mentor, Akihiko, 81, has set an even higher standard for him. “The ultimate bokashi is the evening sunset,” he said.

A subtle craft

Furuhashi’s specialty is a method called “hikizome.” This is a crucial step in the process for making kimono and obi sashes. It determines the base color or colors of the entire fabric before patterns are applied and embroidery added.

Using a color sample from the client, he mixes dyes and applies this mixture to the cloth with a brush, carefully considering how the color will change depending on the weaving method and the fabric texture. There is no manual for such subtle work.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Smartphone cases, furoshiki wrapping cloths and other items that have been prepared with the bokashi technique

The other steps for hikizome, including bokashi, are equally delicate.

During hikkiri, in which a single color is applied, he moves the brush with consistent pressure and speed across the entire tanmono cloth. “Your mind needs to be completely empty” to avoid reflecting any inner turmoil, he said.

The dyeing company was founded in 1972 in the Yodo district of Kyoto’s Fushimi Ward. It moved to its current location in 1980. Furuhashi’s earliest childhood memory is of tanmono cloths of various colors hanging from the ceiling and swaying.

Furuhashi studied business at Ryukoku University. As he encountered nothing that interested him more than dyeing, he joined the family business in 2003. Starting with ji-ire — the process of applying a special liquid to both sides of the cloth before dyeing to prevent unevenness in the dye — he trained diligently under his father.

“I want more people to know about hikizome dyeing,” Furuhashi said.

Five years ago, compelled by this desire, he began producing small items with the bokashi technique. He has made smartphone cases and pouches as well as shawls decorated with acrylic paint. Some of these items have been sold at exhibitions at JR Kyoto Station.

Exploring colors

At the back of the workshop is a “color-matching area” that resembles a kitchen. Here, 12 dyes are mixed in pots to match samples received from clients.

The color varies depending on how the textile is woven and its texture, such as between tsumugi and chirimen fabrics, even though they are the same silk fabrics. He takes a scrap of cloth and, like a painter mixing colors on a palette, painstakingly works to obtain the right color through trial and error, choosing from countless color combinations.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Blended dyes are tested on a scrap of silk for fine color adjustments.

“The tricky ones are ‘antique’ colors, like those between navy, black and purple,” Furuhashi said. “Sometimes I can make it instantly, other times it takes a whole day and still doesn’t work.”

When he was younger, he preferred primary colors. His preferences changed after he began work as a dyeing artisan. Now, he aims for “gentle colors.”

Elegant, graceful, light colors. Neutral colors. To achieve these, he reduces the intensity and adds different colors to restore the original hue. The resulting color is light yet rich.

He creates colors with a traditional beauty beyond words, and with his brush, dyes cloths in shades that are somehow both classic and new.

***

If you are interested in the original Japanese version of this story, click here.

Related Articles

AloJapan.com