Mark Garlick/science Photo Library/Getty Images

Researchers in Japan may have found a way to tackle one of space exploration’s most pressing problems — orbital debris. The neat part is that they won’t even need to physically touch it. Engineers at Tohoku University are currently testing a new propulsion system that could slow down space junk using bursts of plasma. Rather than attempting to clear up all the defunct satellites and space debris using giant nets or robotic arms, this device could fire controlled streams of charged gas at the debris. The knocks from the plasma charges would in turn slow the debris to the point where it drops out of orbit and into Earth’s atmosphere, where it will burn on reentry.

Where this design differs from previous attempts at utilizing the same technology is its bidirectional plasma engine. Earlier plasma concepts were ineffective, as each burst also shoved the removal satellite backward. Associate professor at Tohoku University, Kazunori Takahashi, addresses this flaw with the addition of a second plasma plume that fires in the opposite direction, holding the satellite in one place while still moving the junk.

Lab simulations have shown great promise, with the device delivering three times the decelerating power of older models while still maintaining the balance needed to keep it steady. Early signs suggest the technology could finally make orbital debris removal a safe and viable option without the need for physical intervention.

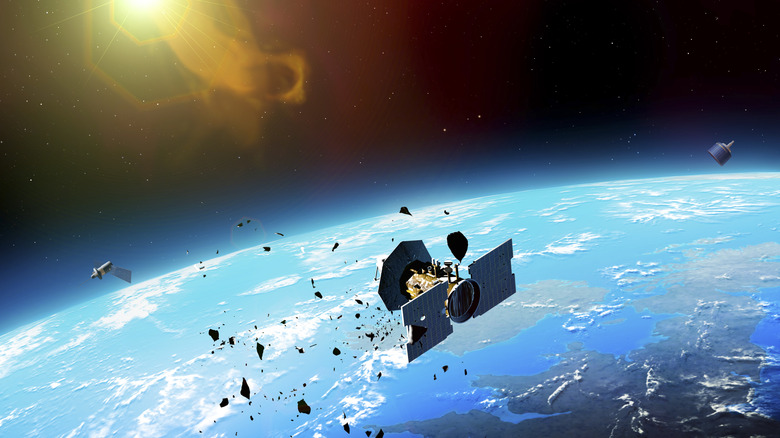

Why clearing orbital debris matters

Think of Earth’s orbit as surrounded by a fast-moving cloud of space junk. Outdated satellites, the shells of old launch vehicles, and bits of machinery from past accidents all constitute this space cloud. Where it becomes really scary is when you realize that each piece races around the planet at thousands of miles per hour, meaning that even the smallest scrap of metal can cause some serious damage. When you consider how many satellites are already in space, this dangerous debris poses a serious threat to their integrity. And the same could be said for missions that have live crew members on board.

History has already shown how destructive these collisions can be. In 2009, a nonfunctioning Russian satellite slammed into a working American one, resulting in thousands of fragments entering the orbit. Each new impact like this increases the odds of runaway chain reactions, where collisions create more debris in a snowball effect. Scientists call this nightmare scenario Kessler Syndrome, and it could eventually make parts of low Earth orbit too dangerous to use.

That’s why non-contact methods like Japan’s plasma thruster are the way of the future. Unlike traditional capture tools that risk knocking into debris, a plasma-powered system can work from a safe distance, therefore decreasing the risk of fueling the problem.

A viable and neccessary solution

Mark Garlick/science Photo Library/Getty Images

One of the most promising aspects of Takahashi’s thruster is its use of argon as fuel as opposed to the standard propellant, xenon, which is more expensive and less abundant. This immediately makes large-scale cleanup missions far less costly and thus more feasible. The research team also introduced a “cusp” magnetic field to better control and direct the plasma to its intended target. This small but ingenious tweak exponentially improved the performance of what are relatively small thrusters, proving their capability of making a big impact in space.

In theory, satellites that utilize this technology could deorbit space debris in as little as 100 days, and the timing couldn’t be better. As more companies, like Elon Musk’s Starlink service, plan on sending an ever-increasing amount of satellites into Earth’s orbit, the problem of space junk will only get worse. All it takes is one unfortunate collision to trigger a devastating chain of events that could, in theory, cripple our navigation, weather services, and global communication.

Tohoku University’s plasma propulsion system is as much a solution to preserving human activity in space as it is an engineering marvel. If it can replicate the positive results it showed in the lab but in real life, this piece of technology will become an instrumental tool in preventing orbit from becoming a junkyard.

AloJapan.com