Koizumi Setsu was the wife of Lafcadio Hearn, who is known for his writings on Japan, including tales of the supernatural. Hearn never systematically learned Japanese, and Setsu was instrumental in supporting his creative endeavors.

Performing for Ghosts

Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things is a masterpiece of weird literature by the writer Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904) based on supernatural tales passed down around Japan. Within this anthology, every Japanese person knows “The Story of Mimi-Nashi Hōichi.”

A blind musician called Hōichi is bewitched by spirits of fallen Heike warriors—members of the Taira clan defeated in the twelfth-century Genpei War—and performs the story of the fateful last battle for them while playing the biwa (a stringed instrument like a lute) in a cemetery surrounded by ghostly fires. A Buddhist priest tries to save him by writing a sutra all over his body, so that he will be invisible to the spirits next time, but he forgets to cover Hōichi’s ears, and these are torn off. The scene where the priest comes to find him and slips on something clammy, which turns out to be blood, is especially intense and memorable. Although the musician recovers, he is known afterwards as Mimi-nashi Hōichi, meaning Hōichi the Earless.

Within this story, the ghostly samurai that summons Hōichi calls for a gate to be opened at one point using the word “Kaimon.” Although he wrote this story in English, by retaining this original term in his phrasing Hearn showed a particular care about the use of Japanese, and indeed the word kaimon is also used at this point in translations of his work back into Japanese.

Creative Partner

Hearn was born on the Greek island of Lefkada in 1850 to a Greek mother and Irish father. When he was two, the family moved to Ireland, but two years later, his mentally troubled mother returned alone to Greece. In an upbringing marked by misfortune, the great-aunt who supported him suffered bankruptcy and he lost his sight in one eye. He migrated to the United States, where he developed an interest in Japanese culture by reading an English translation of the ancient chronicle Kojiki, and in 1890 he traveled to Japan as a correspondent for a US publisher. Later his contract with the publisher was annulled and he moved to Matsue in Shimane Prefecture, where he taught English.

How could Hearn, who never systematically studied the language, collect old Japanese tales and present them to the world in English? And how was it that they were subsequently translated back into Japanese, and have been enjoyed by Japanese readers for more than a century?

Hearn’s wife Setsu is key to the answers to these questions. NHK’s latest asadora (morning drama) series, launching in September 2025, puts the spotlight on the life of Setsu (also known as Setsuko), who supported Hearn. The Japanese title is Bakebake, but for international broadcast, it is known as The Ghost Writer’s Wife. Hearn is remembered as a brilliant English teacher, essayist, and folklorist, but he could not have created Kwaidan or his other retold literature without Setsu.

A commemorative photograph of Hearn and Setsu with their oldest son Kazuo, celebrating Shichi-Go-San around 1896. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

Samurai Daughter?

Having moved to Matsue, Hearn decided to hire a maid to help him adjust to his unfamiliar new life in Japan. This is when Setsu was introduced to him. Hearn had been influenced by images of the country’s women via Japonism, and pictured in great anticipation that the samurai’s daughter he requested would be an elegant beauty. However, Setsu was a robust woman with thick arms and legs. According to an account by the Matsue writer Kuwabara Yōjirō, published in 1950, Hearn openly expressed his displeasure: “This is no samurai daughter; she’s a peasant girl.”

Setsu was in fact a true samurai’s daughter, born in 1868 into the Matsue domain’s prominent Koizumi clan. However, in the social upheaval at the start of the Meiji era (1868–1912), after the shogunate had fallen, many Matsue samurai families went into decline. Setsu, who was one of many Koizumi children, was adopted by relatives called Inagaki shortly after her birth. Competitive and hard-working, she excelled at school, but the family’s financial situation forced her to cut her education short and bring money into the family through weaving. This is how she developed her sturdy body.

It was poverty that brought her together with Hearn, as her first husband, also adopted into the Inagaki family, could not bear the economic hardships and ran away. After her divorce, Setsu returned to the Koizumi family. With the continued need to provide money, despite worries about being looked down on, she saw no choice but to become a live-in maid at Hearn’s house.

A New Shared Language

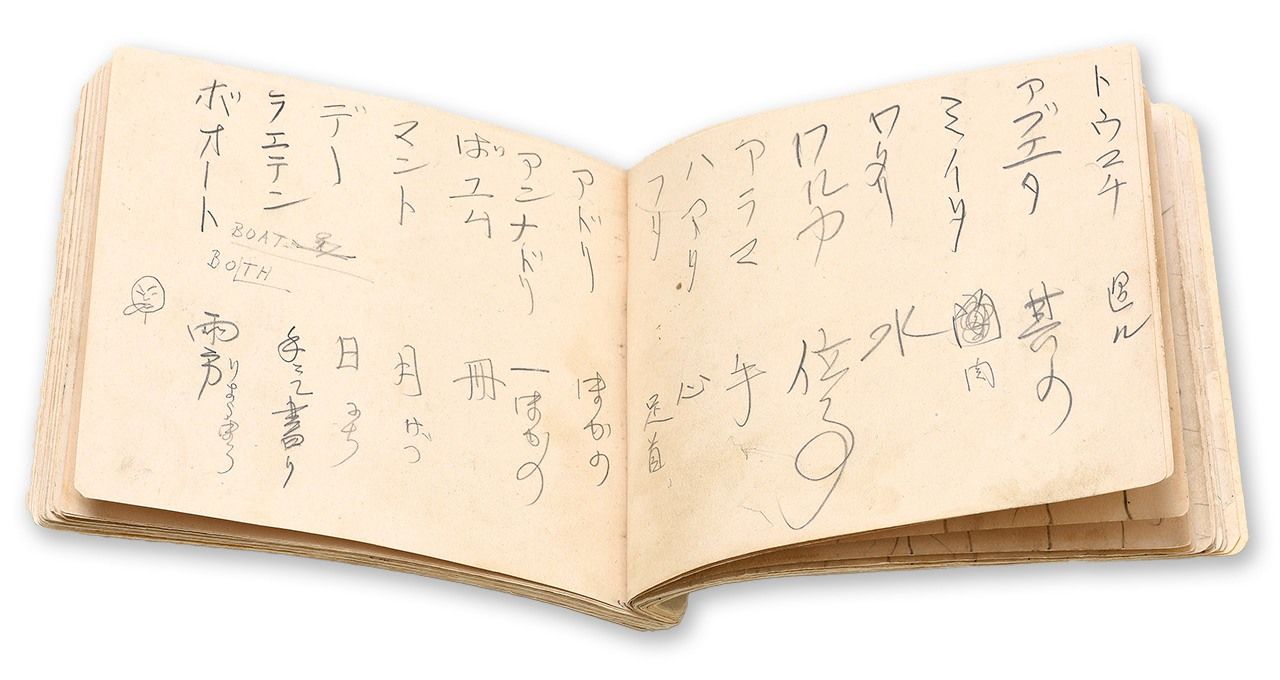

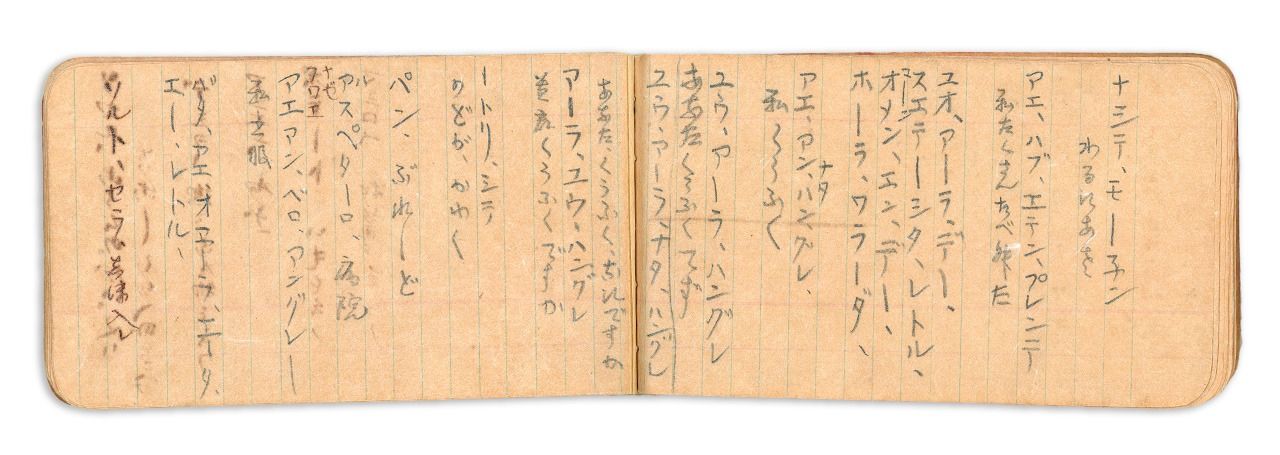

Having become Hearn’s maid, Setsu faced urgent communication issues. Hearn knew almost no Japanese, so Setsu started by trying to learn English from him. She wrote down how to pronounce words like “tomorrow” and “wine” in a small notebook.

Setsu’s English notebook shows her study efforts. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

Other pages in Setsu’s notebook show her putting words together into sentences. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

This way of study did not continue for long, as the two began using an improvised “Hearnish” form of Japanese, where it was fine to leave out particles, and not worry about conjugating verbs and adjectives or the order of verbs and pronouns. For example, sutashion ni takusan matsu no toki arimashita nai was far from grammatically correct, but communicated as “I didn’t have to wait long at the station.” Although this was a strange kind of Japanese, it was easier for Hearn to understand than any level of English spoken by Japanese people. The use of Hearnish brought the two of them closer and was an entry point for Hearn for later exploration of Japan’s oral literature.

When they heard a ghost story together while on a trip to Tottori, Setsu translated into Hearnish and he was overjoyed. Setsu liked such stories and knew many that she could tell him. Along with her hardworking nature, her excellent communication skills meant she could become a partner in his creative endeavors.

An Ideal Woman

In 1893, she gave birth to their son Kazuo; they went on to have a total of four children. Inagaki Tomi, Setsu’s adoptive mother while in the Inagaki family, helped to look after the children, meaning Setsu had more time to assist her husband. When Hearn took Japanese citizenship in 1896, he used his wife’s surname in his adopted name Koizumi Yakumo.

Setsu (left) with her adoptive mother Tomi. (© The Koizumi family)

As well as telling him the tales that she knew herself, Setsu gathered legends from relatives and neighbors and collected old anthologies of stories. One must also not forget how her contributions led to the inclusion of Japanese terms in his works, such as “Kaimon.” The retellings came about through the collaboration of husband and wife.

For Hearn, whose earlier life had been far from idyllic, Setsu contributed not only to his creative efforts but also to his peace of mind. Her later recollections show that she directed maternal love toward her husband as well as her children.

His health declined as he became older, and he became lonely and greatly reliant on me. If I went out, he would wait for my return with the same yearning as a baby for its mother. When he heard my footsteps, he would be overjoyed, joking, “Is that you, Mama?”

Hearn’s works show a strong influence of Setsu as his vision of the ideal woman. For example, in “Story of a Fly,” a young woman works to save money, never dressing nicely, because she wants to earn enough to be able to pay for Buddhist services to be performed for her dead parents. Having achieved this, she herself dies shortly after. In “Story of a Pheasant,” a woman hides a pheasant from hunters, because she believes it to be the reincarnation of her dead father-in-law, and she feels hatred for her husband when he wrings the bird’s neck, planning to eat it. Such stories depict trustworthy, admirable women with strong filial feelings, who are even ready to sacrifice themselves. Hearn is said to have commented that Setsu was not a samurai daughter at their first meeting, but her thick arms and legs were a physical sign of her filial nature.

Koizumi Setsu was more than Hearn’s wife and the mother to his children. She was also a nurturing parent to the many stories that he left.

(Originally published in Japanese on September 17, 2025. Banner image based on a photo of Koizumi Setsu aged around 20. © Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum.)

AloJapan.com