YouTuber Maria films herself during a solo climb of Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the European Alps in this screenshot from her YouTube channel.

Enjoying majestic nature while savoring time alone — this is the allure of solo climbing, which is steadily gaining popularity in Japan. However, about 40% of mountain accidents involve people climbing alone and the activity is known for its high risks, so what is driving people to pursue solo ascents?

‘I can’t stop’

With the approach of the summer climbing season in Japan, a series of posts from solo climbers appeared on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter): “I’ve become addicted to the charm of solo climbing.” “I made a mistake and ended up in danger, but I still can’t stop.” “I like climbing in parties, but true freedom is found in solo climbs.”

At the same time, accidents involving solo climbers are common. This summer, there were cases in Japan’s Northern Alps and on Mount Fuji where a climber, exhausted and unable to move, called for rescue, and where one fell and died. This has sparked critical comments on X, such as “Rescue costs should be fully charged,” and, “Why don’t their families stop them?”

Climbing videos popular

Hikers enjoy a tent stay while climbing in Gifu Prefecture, on July 12, 2025. (Mainichi/Richi Tanaka)

What is it, then, that spurs people on in spite of the risk of mountain accidents? Social media and video-sharing sites have an abundance of climbing-related videos. The content ranges from people challenging difficult peaks to introducing gear and “camp meals” made during tent stays.

One person to introduce such content is Japanese YouTuber Maria, who has about 250,000 subscribers. Her video of climbing Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the European Alps, solo has been viewed over 1.7 million times.

Experiences that only solo climbs can give

“For me, the mountains are a place to test my survival ability. That’s why I prefer rugged mountains to gentle ones,” Maria says.

YouTuber Maria (foreground) records her arrival at the summit of the 3,180-meter-high Mount Yari in the Northern Alps in this screenshot from her YouTube channel.

She chooses mountains that match her abilities, draws up plans, prepares the necessary gear and goes ahead alone. Completing the climbs all by herself brought her a sense of accomplishment she never felt before.

On difficult routes or snowy mountains, there are often no other climbers around. “The sense of solitude, which you can’t usually experience, makes it feel like you’re melting into the great outdoors. I can’t stop doing it,” she says.

She recorded her climbs on video and began sharing the footage in 2020. She also succeeded in traversing the Northern Alps and climbing Mount Tsurugi in central Japan’s Toyama Prefecture — said to be the most difficult in Japan.

Trouble sparks passion for climbing

Taking in the spectacular view near the summit is one of the appeals of solo climbing, as seen in this photo taken in central Japan’s Gifu Prefecture, July 13, 2025. (Mainichi/Richi Tanaka)

Maria’s passion for solo climbing was actually sparked by an incident when she nearly became stranded. She was visiting a mountain in Guatemala to observe the religious rituals of a minority group, which had been the subject of her graduate research at university. The ground was strewn with boulders of lava rock, but based on the altitude, she thought it would take just two or three hours to climb the mountain.

But near the summit, her foot got stuck in the rocks and she couldn’t free herself. She was only lightly equipped, had hardly any food and hadn’t told anyone she was climbing. She eventually managed to get her foot free. She headed in the direction of people’s voices and managed to make it down the mountain, but the incident made her aware of the perils of climbing. “Mountains are places where going without knowledge and skills could be life-threatening,” she realized.

She became aware that reducing risks would make climbing more enjoyable, so she began studying mountaineering on her own.

Sharing safety tips

On her YouTube channel, Maria doesn’t hide her fear, murmuring “this is scary” while climbing a snowy cliff and recounting her own experiences with getting lost.

Solo climbing YouTuber Maria’s book “Solo Tozan no Kyokasho” (The solo climbing textbook), published in April this year, is seen in Kanagawa Prefecture on Aug. 5, 2025. (Mainichi/Richi Tanaka)

As her subscriber count grew, she began receiving comments like, “I started solo climbing too.”

But she became concerned. “I’ve been sharing the appeal of solo climbing, but what about safety?” she thought.

This led her to publish “Solo Tozan no Kyokasho” (The solo climbing textbook), released by Mynavi Publishing Corp., in April this year. The book covers everything from basic gear and walking techniques to building stamina and handling unexpected situations.

“Climbing doesn’t end at the summit. I want people to think about the descent, too,” she says.

Stopping before feeling fear

Maria trains daily on flat ground, prepares gear suited to her fitness and the mountain, and shares her planned route with family.

“I go with solid preparations,” she says.

She also attaches importance to her own sense of fear. “If I feel so scared that I can’t move forward, it means it’s beyond my current ability,” she says. “I make sure to stop climbing a step ahead of that point.”

A boom fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic

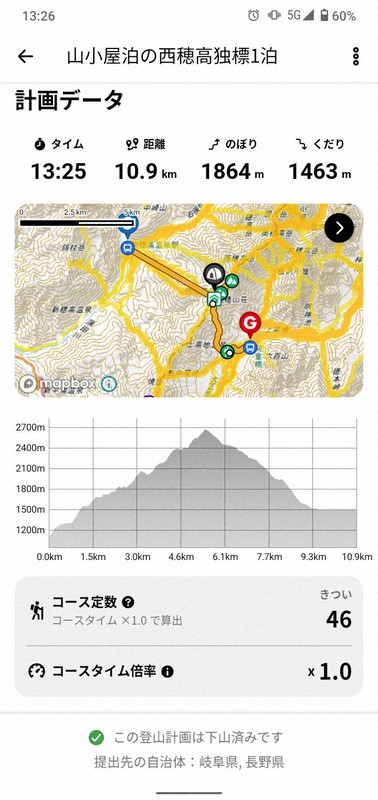

A climbing plan created with the Yamap mountain app is seen in this screenshot from the app.

The popularity of solo climbing also seems to have been boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it harder to have social contact with others.

Hidemi Uema, public relations manager for Fukuoka company Yamap Inc., which offers a trekking map app, notes, “The ‘low mountain boom’ — climbing nearby mountains — also started around that time. Ways of enjoying mountains spread beyond just aiming for the summit to taking photos, making videos and enjoying food and hot springs, and this likely lowered the barrier to climbing.”

Analyzing the situation, Uema said this sense of ease also applies to solo mountain climbing. But she stresses, “You should prepare as much as possible.” She recommends starting with the “three sacred treasures” of mountaineering: hiking boots, a backpack and rainwear. Having a mountain app and access to a location-sharing service for emergencies also provides peace of mind.

“Solo climbers plan their own routes and prepare their own gear. That directly connects to risk management,” she says.

About 40% of mountain accident victims are solo climbers

This photo taken in Kanagawa Prefecture on Aug. 4, 2025, shows essential gear for climbing, including a backpack, boots and rainwear. It’s also reassuring to carry a first-aid kit and regular medication. (Mainichi/Richi Tanaka)

According to the National Police Agency, there were 3,357 mountain accident victims in 2024, down 211 from the previous year. The most common trouble was getting lost (1,021 people), followed by falls (671 people) and slips (577 people).

Among these 3,357 people, 1,311 were solo climbers (down 112 from the previous year), accounting for 39.1% of all accident victims — a persistently high proportion. Solo climbers who get into accidents also tend to have a higher fatality rate than those who encounter trouble while climbing in groups.

A survey by Authentic Japan Co., a company in the southwestern Japan city of Fukuoka that provides the “Cocoheli” service, which transmits the location of mountain accident victims via radio waves, found that 76.67% of the 90 rescue calls received through Cocoheli from April to September 2023 involved solo climbers.

(Japanese original by Richi Tanaka, Digital News Group)

AloJapan.com