A dogu figurine of the Jomon period. (Public domain)

By Damian Flanagan

Over the summer there was a major exhibition of the artworks of Taro Okamoto (1911-1996) on in Paris and I read with interest that Okamato was regarded as a central figure of the Japanese avant-garde. So I started delving into him a little.

Some ideas of his immediately resonated. Okamoto gave a lecture in 1950 in which he outlined his theory of “polarism” (taikyokushugi), arguing against the necessity for a harmony of influences in art and proposing instead that entirely opposing, discordant elements could perfectly co-exist.

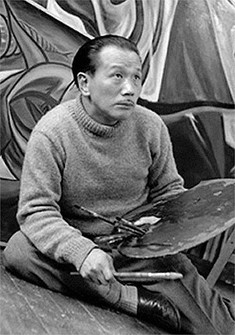

The avant-grade artist Taro Okamoto. (Public domain)

In 1952, in what seems like a major development of this idea, he argued that Japanese artists should not feel constrained by the straitjacket of traditional Japanese aesthetics such as “wabi-sabi”, which ultimately derives from the refined aesthetics of Yayoi period ceramics (c. 300 B.C.E. – 300 C.E.). Instead he argued that completely different aesthetic strands were to be found in Japanese art history, most notably in the roughly authentic, dynamic designs of pots from the Jomon era (14,000 B.C.E. – 300 C.E.) with their strange roped patterns and in the mysterious human and animal figurines (dogu) of the same period. Later, in 1967, Okamoto visited Mexico and began to explore connections between prehistoric Japanese and Mexican art.

Just when you think he might be suggesting an artist be stimulated and influenced by this more primitive art, Okamoto then counselled that the Japanese artist should not feel constrained by this either, but simply use it as a means to smash free of the dead hand of “wabi-sabi” into an art that is radically new, energetic and original. (You can see why Okamoto was a poster boy of the avant-garde.)

These ideas might seem somewhat contradictory and paradoxical, but I found them quite profound. Most nations tend to have certain traditions and mindsets that define them. Yet often, buried beneath these seemingly determinist traditions, and suppressed by them, are a completely different set of traditions and ways of thinking about things. Not only are these other set of traditions different, they are often the exact opposite of one another, with a kind of dominant gene repressing a recessive gene that still lurks somewhere in the national identity.

You could give many examples of this in many nations, but I happened to think first of my own Irish ancestry and the way in which Ireland until quite recently was a nation entirely defined by its Catholic, conservative and agrarian identity. The modern Irish state was created in the 1920s as if these things were an unmovable part of “Irishness”. But buried underneath this, and long suppressed, was a completely different Ireland that was paganistic, firebrand and radical, and keen to embrace urban sophistication. When the Irish poet Seamus Heaney wrote in the 1970s a series of startling beautiful poems about Iron Age bodies being dug up perfectly preserved in Northern European peat bogs, he was also hinting of another Ireland about to be reborn in the 1990s once the hegemony of the Catholic Church was overthrown.

The Tollund Man, a naturally mummified corpse of a man who lived during the 5th century B.C.E.,and the subject of a famous poem by Seamus Heaney (Public domain)

Then my mind turned to Mexico and Octavio Paz and his great work, “The Labyrinth of Solitude”, which attempted to unravel the complexities of the Mexican national character. Paz noted that Mexico was a fusion of two entirely different traditions: the pyramidical style power structures of Aztec civilisation overlaid with the Spanish culture of the Conquistadors at the time of the Counter Reformation.

Yet even within the traditions of Imperial Spain at the height of the Reconquista, there were paradoxical counter currents — at once a fanatical drive to expel Islam from Spain, while at the same time absorbing much of the attitudes, art and academia of Muslim Spain. Mexico as a result tended to operate on certain traditional patterns, while also having the ability to suddenly switch to other completely different strands of cultural legacy.

In this sense, what seems like a culturally distinct and homogeneous society is intrinsically “multicultural” if you dig deeply enough in the hinterland of its national psyche.

In the world today, with ever-increasing currents of human migration and almost instantaneous global spread of ideas, it is hotly debated whether some nations should embrace so-called “multiculturalism” or defend a precious “monoculturalism”. But I wonder whether in fact all nations do not already contain within them competing strands of cultural and aesthetic legacy. For progressives, this is doubtless an argument for the intrinsic appeal of “multiculturalism”; conservatives, by contrast, might argue that a rich seam of “difference” can already be found within a nation’s own traditions and history.

The Coronation of the Aztec King Moctezuma I. (Public domain)

Whatever your feelings towards these matters are, I appreciate the idea that, rather than being constrained by any singularity of cultural tradition, it is the very multiplicity of aesthetic and cultural currents, rising and falling in dominance, that can help spur a person’s own unique creativity.

It’s fascinating to consider the idea that each society contains within itself, sometimes deeply buried but still perfectly intact, the very opposite of what it asserts to be its true self.

@DamianFlanagan

(This is Part 72 of a series)

In this column, Damian Flanagan, a researcher in Japanese literature, ponders about Japanese culture as he travels back and forth between Japan and Britain.

Profile:

Damian Flanagan is an author and critic born in Britain in 1969. He studied in Tokyo and Kyoto between 1989 and 1990 while a student at Cambridge University. He was engaged in research activities at Kobe University from 1993 through 1999. After taking the master’s and doctoral courses in Japanese literature, he earned a Ph.D. in 2000. He is now based in both Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture, and Manchester. He is the author of “Natsume Soseki: Superstar of World Literature” (Sekai Bungaku no superstar Natsume Soseki).

AloJapan.com