Beneath the quiet suburbs of this city 30 miles north of Tokyo lies a monumental engineering project that is as awe-inspiring as it is essential. Known formally as the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel, the facility was built to protect the capital and surrounding communities from the destructive floods that increasingly follow Japan’s typhoons and torrential rains.

The underground complex, buried 50 meters below the surface in Saitama Prefecture, is the largest floodwater drainage system in the world. Its sheer scale has led visitors to compare it to the mythical Mines of Moria from The Lord of the Rings, but the reality is firmly rooted in concrete, steel, and necessity.

an answer to rising waters

The project took 13 years to complete, beginning in 1993 and finishing in 2006, with a total cost exceeding €1 billion. The facility stretches across six kilometers underground and is equipped to store up to 670,000 cubic meters of floodwater—the equivalent of 268 Olympic swimming pools. This massive capacity is designed to offset the risks faced by Tokyo, a city that receives more than 1,600 millimeters of rain annually and where more than four million residents live in zones considered at risk of flooding.

Located in a region where urban sprawl has replaced much of the natural, absorbent ground with pavement and concrete, the channel acts as a pressure valve. It captures overflow from nearby rivers during storms and redirects it toward the Edo River, away from densely populated areas. The system is typically activated seven times a year, mainly during typhoons and periods of intense rainfall.

The facility took 13 years to build at a cost of more than US$1 billion .Credit: MLIT JAPAN

The facility took 13 years to build at a cost of more than US$1 billion .Credit: MLIT JAPAN

a subterranean cathedral

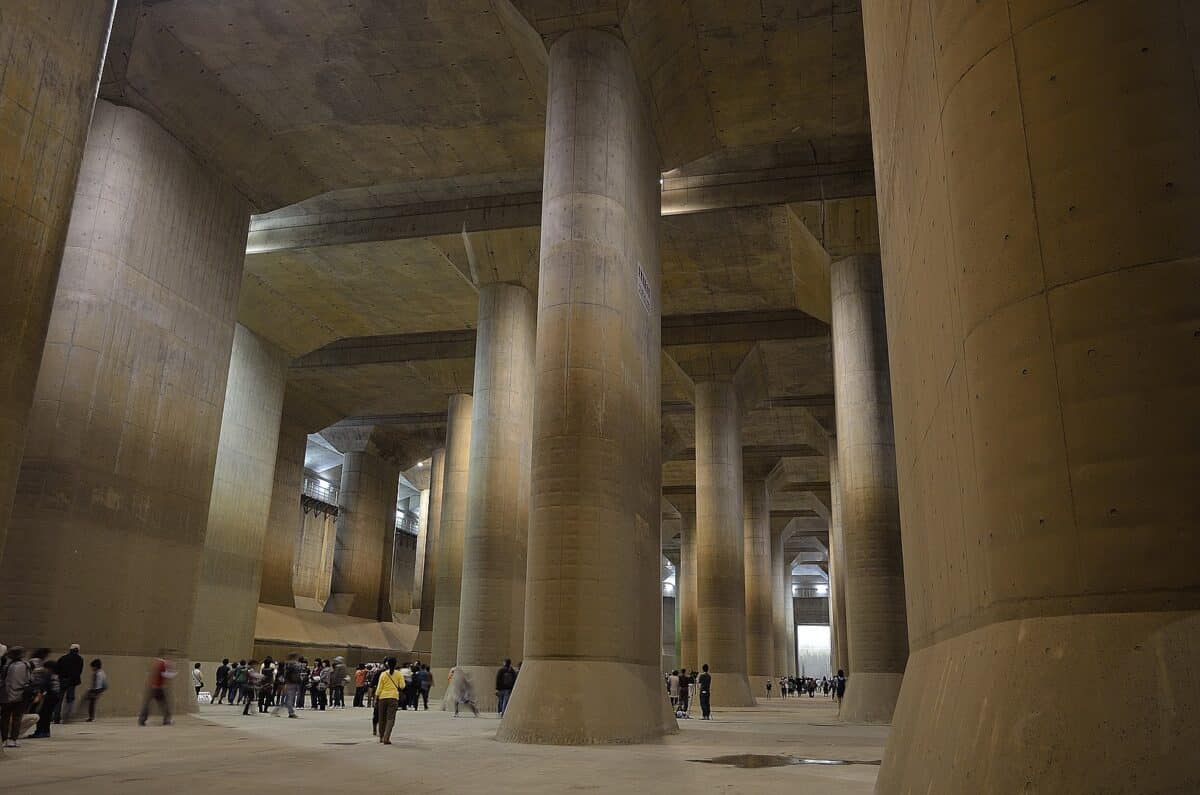

Inside the facility, the main water tank is held up by 59 towering pillars, each 18 meters tall and arranged in symmetrical rows. These concrete supports are so large that each shaft could theoretically accommodate the Statue of Liberty. The structure’s vast, dimly lit central chamber, with its towering columns and hushed atmosphere, has earned it the nickname “the underground shrine.”

Visitors who descend the narrow stairways into the cavern report an immediate sense of awe. One tourist told The South China Morning Post, “The moment I stepped down the stairs and saw the entire space, I was astonished.” The space evokes the ancient Roman Pantheon or Istanbul’s Basilica Cistern, but unlike those historic sites, this one is entirely modern—and still operational.

Pressure control water tank. Credit: Wikipedia

Pressure control water tank. Credit: Wikipedia

protection, not domination

The facility’s impact has been significant. According to Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, the system has prevented more than €1 billion in potential flood damage since its activation. Yet, its reach is not total. Only three of Tokyo’s wards, along with a few neighboring towns in the northern part of Greater Tokyo, are directly covered by the system’s protection.

For officials like Nobuyuki Tsuchiya, deputy director of the Japan Riverfront Research Centre, the lesson is clear: cities must think long-term. “Gérer l’eau, ce n’est pas juste réagir,” Tsuchiya said. “C’est anticiper pour que dans 100 ans, nos villes soient encore vivables.” The facility is only one component of a national strategy that includes reinforced levees, surface reservoirs, redesigned riverbanks, and climate-adaptive urban planning.

from engineering to instagram

Though built with functionality in mind, the underground complex has taken on a second life as a tourist attraction. Originally off-limits to the public, it now hosts guided tours, but with strict limitations on availability and time slots.

Descending into the giant tank, visitors often wear construction boots to navigate the slick concrete floors. The site’s eerie atmosphere, diffused lighting, and raw scale have made it popular among photographers and social media influencers seeking a dramatic backdrop.

Still, its primary role remains clear. Silent, watchful, and ready, the chamber beneath Kasukabe stands as a modern sentinel—its architecture an unspoken reminder that nature’s power can be channeled, but never ignored.

AloJapan.com