World fairs have served as a stage for international business by showcasing the latest technology and goods of the era. A new book describes how Japan used world expos starting from the end of the Edo period to promote tea to the West, spreading Japanese tea culture to the rest of the world.

Japan’s World Fair Debut

The prototype for today’s international expositions, where countries from around the world showcase new products and their specialties and which provide opportunities for cultural exchanges and business talks, is said to be the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851.

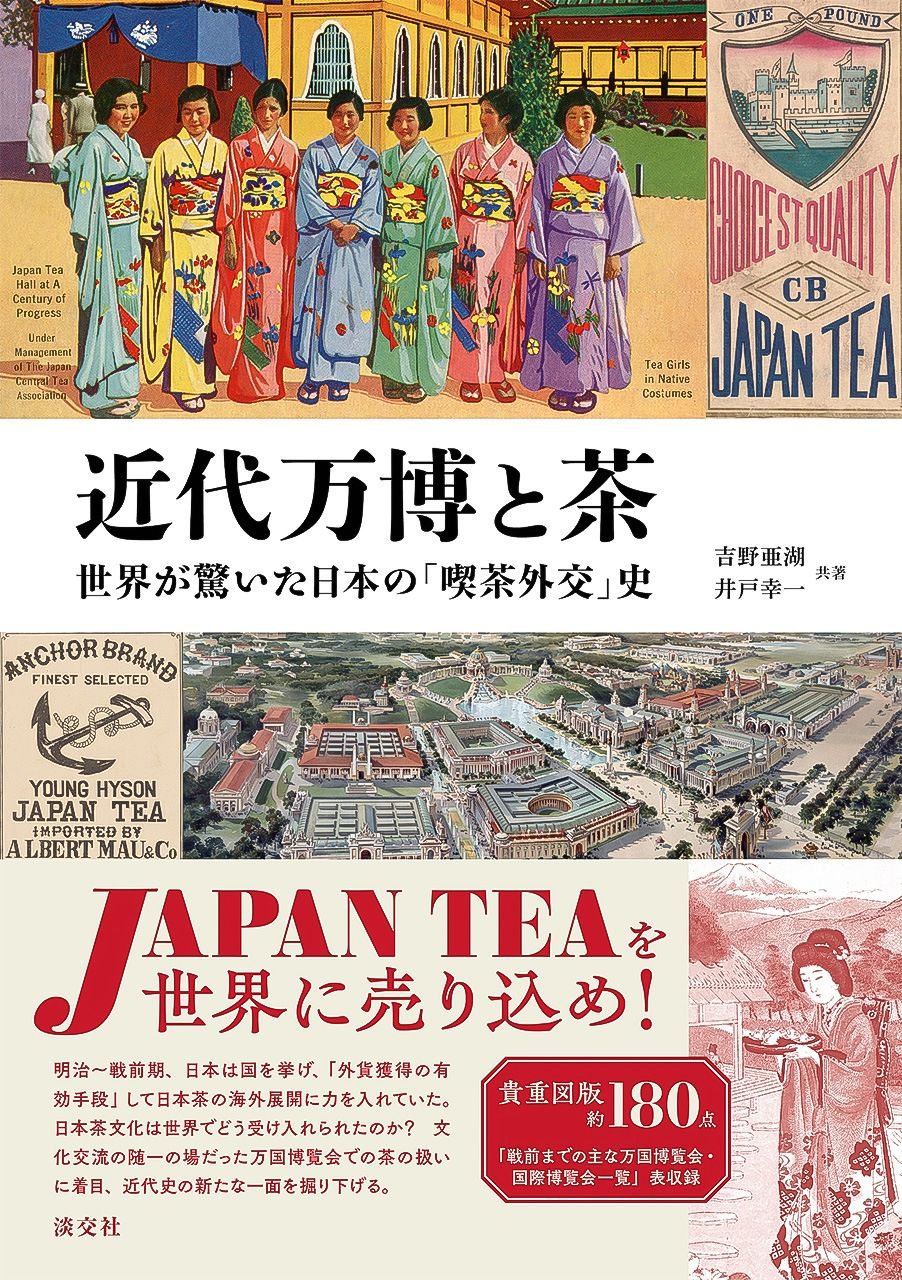

Scholars Yoshino Ako and Ido Kōichi explore Japan’s participation in modern world’s fairs, starting from the 1867 Paris Exposition through to the 1933–34 Chicago World’s Fair. In Kindai banpaku to cha: Sekai ga odoroita Nihon no kissagaikō shi (Modern World Expositions and Tea: A History of Japan’s Tea Diplomacy), the authors, who researched newspaper reports and other historical materials and visited former expo sites, provide a chronological rundown on the connection between these fairs and the spread of Japanese tea and tea culture.

The Birth of Wakōcha Exports

The Tokugawa shogunate sent a delegation from Japan, headed by Tokugawa Akitake, younger brother of shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, to the 1867 Paris Exposition, organized by French emperor Napoleon III. Among the delegation’s members were Shibusawa Eiichi, later known as the “father of the Japanese capitalism,” and at the shōgun’s request, representatives of the powerful domains of Satsuma and Saga.

The book relates that the Japanese pavilion’s tearoom created a sensation among Parisians and that the exhibit was awarded a silver medal by Napoleon III. Japanese tea was featured, marking the start of the relationship between ocha and world expositions.

A photo from the book showing kimono-clad women at the Japanese pavilion’s tearoom at the 1867 Paris Exposition. (© Album/Quintlox/Kyōdō)

In 1873, Saga Prefecture exhibited kōcha, or black tea, at the Vienna World’s Fair. While Japan’s principal tea beverage was unfermented green tea, but authorities from Saga had learned at the 1867 Paris Exposition that black tea, created by fermenting tea leaves, was preferable for export to Europe. Subsequently, tea growers throughout Japan began producing wakōcha, black tea grown and produced in Japan, which, according to the authors, was a historic moment for the Japanese tea industry. Incidentally, Buddhist monk Baisaō (1675–1763), founder of senchadō variation of the Japanese tea ceremony distinguished by its use of green tea leaves rather than matcha, hailed from Saga, the birthplace of wakōcha.

Introducing the “Way of Tea”

International expositions were also a way of introducing Japan’s tea culture to the world. At the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia, held to mark the 100th anniversary of US independence, a list of exhibits contains three references to “cha-no-yu.” The authors note in their book that this may be the first mention of sadō, the Japanese tea ceremony, in an official document.

At the 1878 Paris Exposition, the Japanese pavilion included a tea house; a pamphlet in French explained the history of sadō. According to the book, industrialist, art collector, and founder of the Mitsui trading house Masuda Takashi (1848–1938) dispatched three carpenters from Japan to erect the structure. Later in life, Masuda became a tea ceremony master under the name Donnō.

Okakura Kakuzō (or Tenshin, 1868–1913), best known for his The Book of Tea that was published in New York in 1906, acted as a presenter of Japan’s tea culture at two world fairs. He wrote an explanatory pamphlet in English about the Hōōden tea house at the Japanese pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, and at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, he spoke on the artistic cachet of “cha-no-yu.”

Spotlight on Japanese Women

Although featuring Japanese tea at world expositions first and foremost reflected the government’s export promotion policy, tea also played a role in promoting Japanese culture, which is described in the book through the contributions of Japanese women.

The Japanese pavilion’s tearoom at the 1867 Paris Exposition, Japan’s first world’s fair, was attended by three geisha who had traveled to Paris for the occasion. At the time, the Japanese women were an object of fascination among the French public, and many people flocked to see them.

At the Panama–Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915, the Japanese pavilion featured a Japanese tearoom made of cypress that was attended by seven young “tea girls” wearing kimono with long, flowing sleeves. A February 2, 1915, article in the local Japanese-language newspaper The Japanese American News reported on the women’s arrival in San Francisco, describing them as “well-educated young ladies from good families” that included the daughters of a high-ranking government official and of a navy admiral.

At the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, 10 nisei (second-generation Japanese-American) women were hired to staff the Japanese pavilion’s tearoom. They were also featured on picture postcards and in advertising materials for Japanese green tea.

That fair also showcased the Rinkōtei tearoom, which was furnished with tables and chairs. The tearoom had been donated by Masuda to foster friendship between Japan and the United States. The tea was prepared by the 20-year-old daughter of a Japanese surgeon who had been sent from Japan for the occasion.

Japanese Tea Presence Boosted at US World Fairs

During the days of empire when the Western powers ruled the world, tea was an important international commodity. Green tea and semi-fermented oolong tea along with black tea grown in China and exported to Europe and North America dominated the market at the time. The British Empire, dependent on tea imports from China, fought back by setting up huge plantations for Assam black tea in its colonial territories of India and Ceylon (today Sri Lanka).

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, when Japan established its own empire, green tea was exported mainly to the United States. In the aftermath of the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), Taiwan became a Japanese colony, and oolong and other teas from Taiwan were also exported to the United States via Japan. The book includes details about the Taiwan tearooms at the St. Louis, San Francisco, and Paris world expositions.

Robert Hellyer, a researcher of the modern tea trade, also makes an appearance in the book. Hellyer is a descendant of the nineteenth-century founders of Hellyer & Company, a Nagasaki-based tea exporter that Hellyer mentions in his book Green with Milk and Sugar: When Japan Filled America’s Tea Cups. In the work, Hellyer describes how Japanese green tea became popular in the US Midwest beginning in the late 1800s, so much so that it was called “green tea country.” Hellyer believes that the world’s fairs in the midwestern cities of St. Louis and Chicago helped raise awareness of green tea in the region. But this tea trade ended abruptly with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Japan lost its empire with its defeat in 1945, and the government’s prewar ambitions of having Japanese tea take over global markets evaporated with it.

Yoshino and Ido conclude their book by noting that Japanese tea exports have begun rising again.

Japan has, of course, gone on to host six international expositions of its own, starting with the 1970 Osaka Expo, the first held in Asia. I have heard that many events at the current exposition, Expo 2025 Osaka Kansai, also incorporate the concept of omotenashi hospitality embodied by sadō. The Playground of Life: Jellyfish Pavilion, especially, exemplifies the spirit of tea, and I am looking forward to new relationships emerging between Japanese tea and world expositions.

Kindai banpaku to cha: Sekai ga odoroita Nihon no kissagaikō shi (Modern World Expositions and Tea: A History of Japan’s Tea Diplomacy)

By Yoshino Ako and Ido Kōichi

Published by Tankōsha Publishing in February, 2025

ISBN: 978-4-473-04660-4

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)

AloJapan.com