FX168 Financial News Agency (North America) reported that over the past few weeks, yields on Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) have surged to their highest levels since the 1990s, drawing attention in Tokyo and around the world. On the surface, this latest spike is a response to reports that the government is considering ‘temporarily reducing the consumption tax on food.’ Given the persistent rise in the cost of necessities — for instance, rice prices have doubled — the proposal for tax cuts has resonated strongly in an economy where living costs have hardly changed for this generation.

According to projections by Benjamin Shatil, a senior economist at JPMorgan, the reduction in food taxes could result in an annual revenue loss amounting to approximately 1% of GDP. While this might be manageable on its own, it becomes challenging when considered alongside potential cuts to social security contributions, increased defense spending, and other pro-growth policies. As other governments have learned through painful experiences: lowering consumption taxes is easy, but raising them again is extremely difficult. By pushing up bond yields, markets are signaling skepticism about whether any so-called ‘tax cuts’ would truly be temporary.

Over time, Japan’s high total government debt means that rising interest rates will lead to higher interest payments. As indicated by volatility in the bond market, Japan faces a delicate balancing act between managing growing interest expenditures and maintaining fiscal spending. From JPMorgan’s perspective, the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) exit from years of ultra-loose policy risks driving government bond yields even higher.

(Source: LSEG, Financial Times)

(Source: LSEG, Financial Times)

Admittedly, the pace of interest rate hikes by the Bank of Japan has been exceedingly slow. Governor Kazuo Ueda spent nearly two years gradually raising rates to 0.75% (the highest level since the 1990s). However, despite the sluggishness in hiking rates, the Bank of Japan has moved swiftly to reverse another legacy policy.

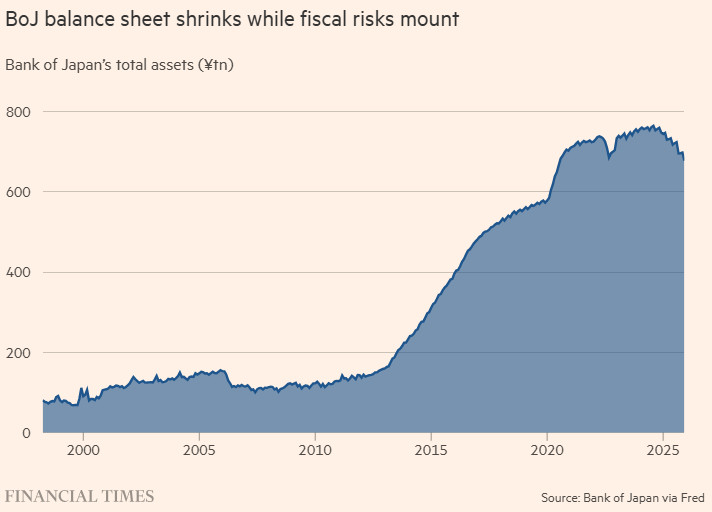

During the years of quantitative easing (QE), the Bank of Japan accumulated vast amounts of government bonds to ease monetary conditions. Now, it is allowing some of those bonds to mature without refinancing, effectively transferring them back to private sector investors — essentially constituting ‘quantitative tightening’ (QT) at a surprising speed.

(图源:日本央行、Fred、金融时报)

For a bond market that, until recently, was almost entirely controlled by the central bank (which once held around 50% of the market share), this marks a significant turning point. According to estimates by JPMorgan, as purchases intended to replace maturing bonds decline, the BoJ’s own roadmap shows that its balance sheet will shrink by an additional 13% of GDP this year. For any major central bank, this represents a dramatic reduction process; relative to Kazuo Ueda’s cautious rate hike approach, this move is particularly striking. The crux of the issue lies here: QT means that a larger proportion of government debt must be absorbed by the private sector, in addition to any potential increase in expenditures.

(Source: LSEG, Financial Times)

Of course, the Bank of Japan can adjust the pace of its balance sheet reduction based on rising yields. It could resume large-scale bond purchases to alleviate the burden on commercial banks, life insurance companies, and pension funds absorbing government debt issuance. However, if such adjustments are made under market pressure and perceived as a signal of fiscal dominance over monetary policy (i.e., ‘monetization of fiscal deficits’), JPMorgan suspects that the long-term victim will likely be the yen.

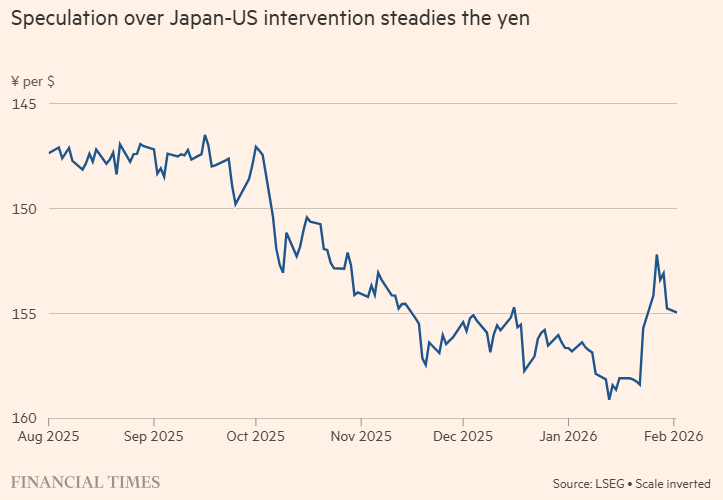

Against this backdrop, rumors of possible cooperation between Japan and the United States to support the yen have temporarily stemmed its decline. Although U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent dismissed the possibility of supporting the yen by selling dollars, reports indicate that the New York Federal Reserve recently conducted ‘rate checks’ — a move aimed at verifying current market exchange rates, often a precursor to currency intervention. If this action was coordinated with Japanese authorities, it would represent a significant and unusual sign.

Ahead of Japan’s general election this weekend, the yen’s retreat from the unsettling 160 mark against the dollar is good news for the government. However, direct currency intervention (should it occur) could complicate matters. Such intervention might trigger speculation (whether accurate or not) that Japan’s Ministry of Finance could reduce its holdings of U.S. Treasuries to raise funds for purchasing yen.

This may temporarily boost the yen and calm volatility in Japan’s government bond market, but at the potential cost of pushing up U.S. Treasury yields, an outcome the U.S. government is unlikely to accept. Conversely, if yields on Japanese government bonds continue to rise, prompting Japanese capital to withdraw from the U.S. debt market and return home, it could produce a similar ‘spillover’ effect.

Volatility that begins in Tokyo is not necessarily destined to end there.

AloJapan.com