The snap election called by Sanae Takaichi, the prime minister of Japan, has unleashed a surge of expectation among young female voters.

The surprise news that the country will be going to the polls next weekend came at the same time as Japan’s annual “coming of age” ceremonies. Held across the country, from village halls to vast concert arenas, the celebrations mark the moment when an entire cohort of 20-year-olds is formally welcomed into adulthood and told they represent the nation’s future.

This year’s ceremonies have helped fuel a social media phenomenon known as Sana-katsu, loosely translated as “the Sanae craze”. Young female fans have dressed up like the prime minister, buying the designer brands she favours, from her feather-down LL Bean coat to her upmarket Hamano handbag. the Grace Delight tote bag, now universally known as the “Sanae Bag”, has sold out nationwide and has a six-month waiting list, even though it costs about $900, around two-thirds of the typical monthly salary for this age group.

Takanori Kobayashi, of Hamano Leather Crafts Co, with an example of the Grace Delight tote bag used by Sanae Takaichi, below

EUGENE HOSHIKO/AP

“She’s made it to the top against all those men, and is not afraid to tell the truth,” said Hina, a 20-year-old intent on giving the prime minister her support next month. “She’s also very stylish.”

Beyond the hype, however, polling suggests the craze has had a real political impact. According to a Studyplus survey, a quarter of young people who previously expressed no interest in politics said they were politically engaged thanks to the trend, while another quarter said they were significantly more engaged than before.

One survey by Sankei FNN reported approval ratings of more than 90 per cent among 18 to 29-year-olds. Her popularity is also high among young men, although not as substantial as among women; a youth survey by the Nippon Foundation found 44 per cent of women had “new hopes and expectations” about Takaichi, compared with 27 per cent of men.

A Toyota HiAce used in the 2024 Liberal Democratic Party leadership race, displayed at a museum in Nara

YUICHI YAMAZAKI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Japan ranked 118th out of 148 countries in the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Gender Gap Report 2025. Although it is among women that her appeal has been most intense, Takaichi’s rise has also tapped into a deep reservoir of frustration among younger voters of both sexes, whose living standards are predicted to remain far below those enjoyed by their parents and grandparents.

Robert Dujarric, a political analyst at Temple University in Tokyo, said: “Takaichi is certainly different from your standard LDP [Liberal Democratic Party] leader. And while it matters that she’s a woman, it’s also important that she isn’t from a prominent political dynasty, isn’t wealthy, and didn’t attend one of the very top universities.”

Takaichi ringing the bell to mark the last trading day of the year on the Tokyo Stock Exchange last year

EUGENE HOSHIKO/AP

Raised in the Nara prefecture, Takaichi was offered places at two elite private universities in Tokyo, but her parents refused to pay the fees. In a recent biography she recalled her disappointment, describing an era when a girl’s higher education was seen as wasteful. Her mother encouraged her instead to become a “crimson rose”, “exhibiting feminine grace while remaining armed with thorns”.

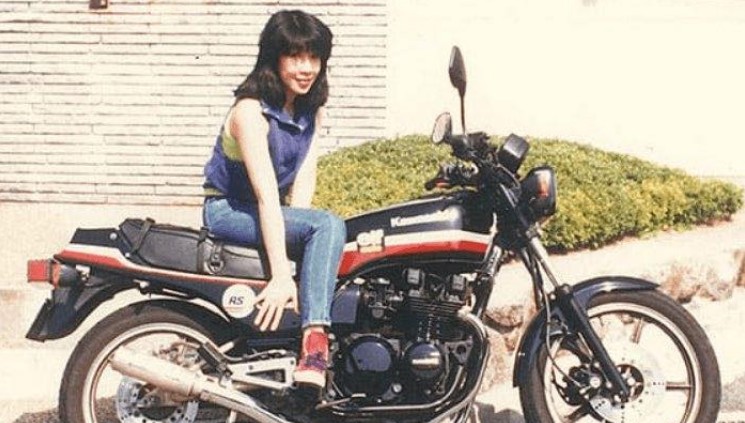

Undeterred, she commuted six hours a day to study at Kobe University, worked part time to save for her first Kawasaki motorbike, and later became drummer in a rebellious heavy metal band, inspired by British acts such as Iron Maiden.

Her recent jam session with the South Korean prime minister went viral among young Japanese.

Lee Jae Myung, the South Korean president, with Takaichi

EPA

The contrast with her predecessor, Shigeru Ishiba, could hardly be greater. A self-confessed trainspotter and model-maker, Ishiba was once said to have greeted Russia’s defence minister with bags under his eyes, after staying up all night to painstakingly assemble a model Soviet aircraft carrier as a welcome gift.

• Uwa! Japan’s PM is a heavy metal ex-biker

Takaichi’s strategy of courting the youth vote, which was enlarged by 2.5 million ballots when the voting age was lowered from 20 to 18 in 2015, appears to be working. Some of her policies are clearly targeted at young voters, who are particularly concerned about the cost of living, including tax credits to bolster take-home pay for young workers, ands corporate breaks for firms that provide in-house childcare.

But her policies do not always fit a feminist narrative. Critics argue that the social media hype — and Takaichi’s rebellious heavy metal past — obscure the reality of her conservatism.

In October, she urged colleagues to work “like a horse” and promised to abandon the very notion of work-life balance, vowing to “work, work, work, work and work” — a remark that won a Japanese catchphrase of the year award.

Like her idol, Margaret Thatcher, she wastes little time on sleep, a badge of honour in Japan’s punishing work culture. But when she boasted she could survive on just two to four hours a night while caring for her husband, who is paralysed after a recent stroke, feminists reacted angrily.

Yayo Okano, a professor of feminist political theory at Doshisha University, said: “She’s a woman who supports her party’s patriarchy, where men are supposed to overwork at the centre of society while women are there to support them through unpaid care.”

Takaichi compounded the backlash by dismissing concerns about her lack of sleep with a quip that it was probably only “bad for my skin”, widely interpreted as a jibe at trivialised female worries. Critics labelled her an “honorary man”. She was also criticised for caving in to Japan’s chauvinist traditions by not presenting the trophy at the first big sumo tournament of the year. Women are considered “unclean” in sumo custom, and barred from entering the dohyo ring.

Kiyomiya Yui, a recent graduate living in Tokyo, said: “I suspect that to succeed in a male-dominated political world, she feels forced to act even more ‘macho’ than the men. Claiming she only needs two to four hours’ sleep a night sounds impossible to me.”

Takaichi supports a tough stance on immigration, traditional family structures, and the continued ban on same-sex marriage. She has also backed maintaining the male-only line of succession to the Chrysanthemum Throne, despite the emperor having only a daughter. She opposes allowing married couples to have separate surnames, although when she remarried her husband, he took hers, which is highly unusual in Japan.

Supporters watching Takaichi making her first speech at the kick-off of the official campaigning for this month’s general election

FRANCK ROBICHON/EPA

“Her media popularity makes me anxious,” said Yui. “Her views are exclusionary rather than inclusive, and it feels more like she’s trying to ‘make’ women have children rather than creating a society where people want to have them.”

When she took office, Takaichi promised Nordic-style levels of female representation in her new government, but appointed just one other woman to her 19-member cabinet. Supporters argue that, with women making up only 15 per cent of MPs, her options were limited.

As a former minister for gender equality, Takaichi pushed through few substantive reforms, perhaps constrained by the demanding other half of her portfolio — boosting birth rates. She has, however, been praised for breaking taboos by speaking openly about matters such as the menopause and the need to improve women’s health services.

In a country desperate for both real and metaphorical rejuvenation, visitors are often surprised to learn that the LDP has governed Japan for almost 65 of the past 70 years. “The LDP has been in power so long it’s impossible to imagine politics without them,” said Hiromichi, a male student at Tokyo University, where the undergraduate gender gap is still 80:20 in favour of men. “I would just like real change, but I don’t think it will come from young voters, because they’re looking at image instead of policies.”

For Sana-katsu fans, however, the determination and energy of Japan’s first female prime minister matter as much, if not more, than her policies. “We need to look forward like Takaichi and get on and make the changes needed,” said Maris, a 22-year-old kindergarten worker.

AloJapan.com