SAPPORO – Many would think of whisky or fresh milk when it comes to Hokkaido-made beverages.

Add wine to the list. Mr Takahiko Soga’s pinot noirs, meticulously crafted in the terroir of Yoichi that is better known as the home of Nikka Whisky, have achieved cult status among connoisseurs.

The limited-production wines are so popular that one bottle of Domaine Takahiko wine can command thousands of dollars in Michelin-starred restaurants worldwide. The annual harvest in October draws an international pilgrimage of oenologists and sommeliers eager to volunteer on his 4ha field.

The 52-year-old is not native to

Hokkaido’s burgeoning wine country

. Born into a wine-making family near Nozawa Onsen in mountainous Nagano prefecture, Mr Soga packed his bags for Yoichi in 2009 with nothing but conviction that the town’s potential for high-end wines will only grow as climate change pushed the so-called “wine belt” northwards.

“I took a gamble, and in a sense, I won,” he gamely said.

Mr Takahiko Soga’s wager has paid off handsomely as a pioneering vintner in Hokkaido.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

His wager has paid off spectacularly as a pioneering vintner in Hokkaido, where the number of wineries has tripled to 73 in the decade to May 2025. One in four of them is located in Yoichi, the rapid expansion being a direct consequence of climate change creating surprisingly favourable viticultural conditions.

This is part of the changing face of Hokkaido caused by global warming, altering the types of produce from the island and also affecting the seasons, with more instances of extreme weather events like intense “guerilla rainstorms”, as the Japanese call it, and droughts, especially during summer. Hokkaido endured

an exceptionally brutal summer in 2025

, with the mercury 3.7 deg C higher than average.

And that is where Mr Soga’s ebullience has given way to concerns that the drastic temperature fluctuations have impacted the quality of his wines. In 2025, he took out a loan to construct a barrel cellar to ensure wine can be stored in cooler conditions.

Mr Takahiko Soga, who produces Domaine Takahiko pinot noir, with wine grapes harvested from his 4ha vineyard in Yoichi, Hokkaido.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

The Straits Times visited Hokkaido twice in late 2025 to observe the impact of climate change on what has traditionally been Japan’s breadbasket.

Warmer climes are starting to leave an indelible impact on the prefecture’s prized agriculture and fisheries industry, which means the food it produces and exports are changing even as experts are racing against time to protect farming livelihoods by creating heat- and pest-resistant cultivars.

Aquaculture, meanwhile, has become more important to mitigate the effect of warmer seas on wild fishing.

South Korean tourists walking by Lake Shikotsu, as Mount Fuppushi is seen behind, in Shikotsu Toya National Park in Hokkaido on Dec 10, 2025.

PHOTO: AFP

And as seasons start to change, there is a clear risk to its hospitality industry. Hokkaido, often associated with cooler summers, has suffered sweltering summers with the mercury surging to 39 deg C in the eastern city of Kitami in 2025. Warmer winters, too, would threaten the volume and quality of snow that winter sports enthusiasts flock to the island for.

Warmer temperatures could also well trigger more intense blizzards that can cause travel chaos, like

the one in December 2025

.

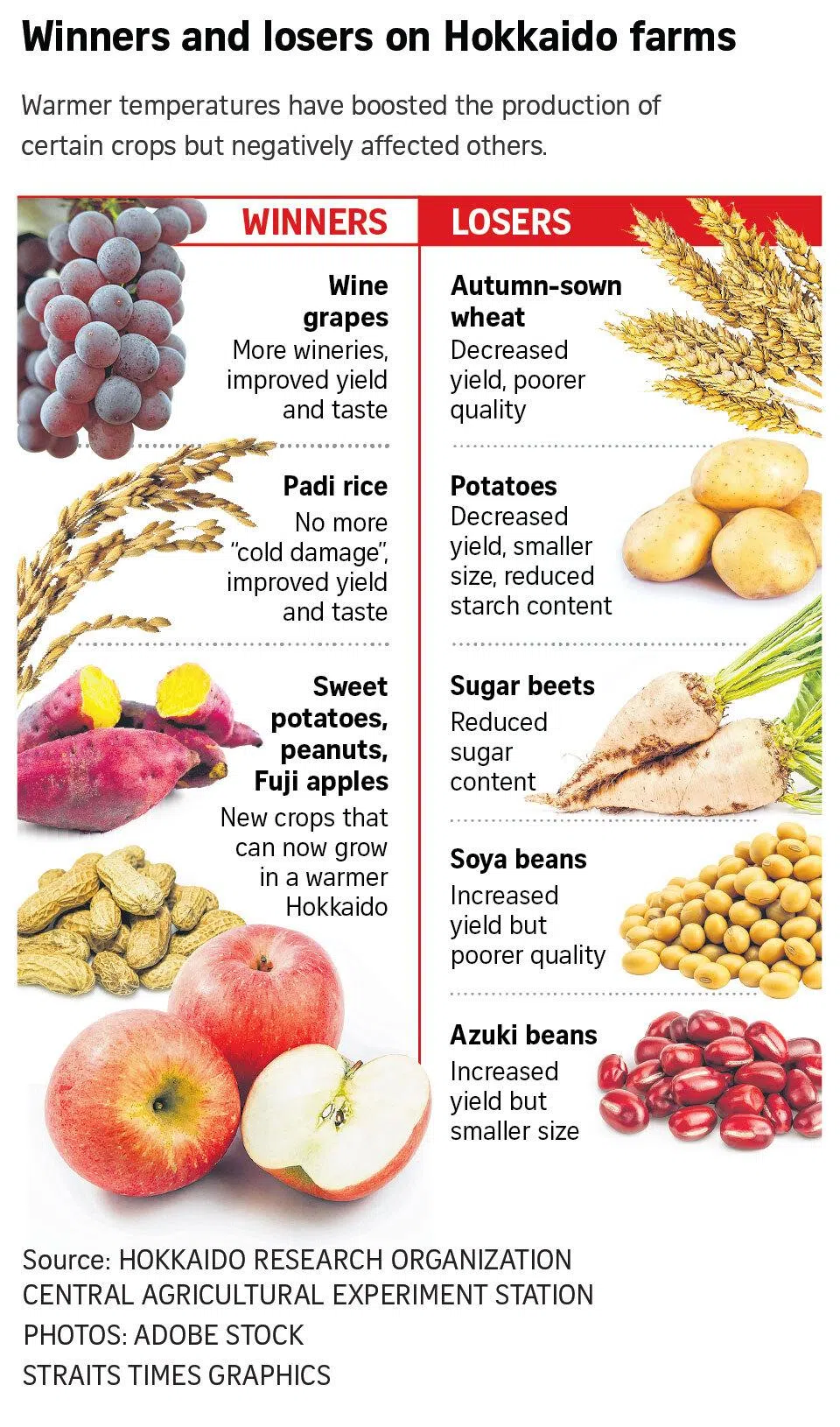

While it is now more conducive to grow crops such as wine grapes, rice and eggplants, the quality of other produce like potatoes, onions and beans has been affected by warmer weather.

Tropical and subtropical marine species like amberjack and puffer fish are now being caught in the warmer waters off Hokkaido.

Meanwhile, catches for seafood like mackerel and squid are declining, as are those for salmon, for which the 2025 autumn catch was its worst on record at 5.6 million, down 64.1 per cent from a year ago, according to prefecture figures on Jan 13. Salmon prices on the market are now 1.5 times of previous years’.

Production of Hokkaido’s famous scallops, while previously stable with moderate fluctuations, is likely to decline 17 per cent to 336,000 tonnes for the year ending March 2026, according to Hokkaido Fisheries Association forecasts.

These changes matter not just to Japan’s food security, but also the island’s global image. Food is one of the things that make Hokkaido popular among Japanese and the 2.83 million international visitors it saw in 2024.

Scallops being unloaded at Shibetsu Fishing Harbour in Hokkaido on Jan 17, 2024.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

There are other changes at work. Global warming is also an engine of reinvention, giving impetus for the prefecture of five million people to establish itself as a dynamo for clean energy.

Hokkaido’s vast untouched expanses and favourable climate conditions have resulted in renewable energy comprising 40.4 per cent of the prefecture’s energy mix, outpacing the 26 per cent nationwide.

This would not translate into any direct impact for visitors to Hokkaido today, beyond how they will notice more wind and solar farms and batteries for electricity storage as they travel from New Chitose Airport to destinations like Niseko, Biei or Asahikawa.

Wind turbines seen at the Ishikari Bay New Port Offshore Wind Farm, located in Hokkaido’s Ishikari Bay New Port harbour area.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

But this is a statement of how Hokkaido sees its responsibility towards protecting its rich natural environment. Only by taking steps towards carbon neutrality can irreversible changes to the climate be prevented, thus ensuring that in the long run, generations of future visitors will still be able to continue enjoying its powder snow in winter and excellent produce.

And Hokkaido believes it has the potential to boost Japan’s overall woeful energy self-sufficiency rate of 15.2 per cent.

“I believe that Japan cannot achieve carbon neutrality without the success of Hokkaido’s clean-energy projects,” averred Ms Kaori Nishiyama, Sapporo’s director-general of green transformation (GX) promotion.

GX is how Japan describes its key policy to reform its economy and social systems to achieve decarbonisation and economic growth simultaneously.

“Hokkaido ranks first among Japan’s 47 prefectures for its wind, solar, hydropower energy generation, and second for geothermal,” she said, adding that there are plans to build power transmission lines that will allow Hokkaido to directly share power with the Tokyo Metropolitan Region.

Mr Sean Kidney, chief executive of non-government organisation Climate Bonds Initiative that aims to mobilise global capital for green projects, said: “The challenge for Japan is whether it can transition and phase out fossil fuels fast enough, and Hokkaido is central to this as the powerhouse of energy security going forward.”

He added: “There’s no technological barrier; there’s no pricing barrier. The barrier is policy in Japan.”

Hokkaido’s aspirations to be a clean energy powerhouse dovetail with its ambition to be Japan’s digital economy hub.

It hosts a semiconductor foundry and is actively wooing data centres, both of which are notorious for their huge appetites for energy.

Mr Yasumitsu Okazaki of the next generation energy department at Hokkaido Electric Power Company (HEPCO) said: “The power demand in Hokkaido had been expected to gradually decrease (due to its declining population), but now everyone is staking their expectations on its renewable energy potential as the energy demand is forecast to rise 1.5 times by 2040.”

But stakeholders believe Hokkaido can meet rising energy needs in a green way, given its rich potential for renewable energy. The cooler temperatures, relative to elsewhere in Japan, also make it more energy- and cost-efficient to host semiconductor foundries and data centres.

The city of Chitose is home to Rapidus, the government-backed chipmaker that hopes to mass-produce advanced 2 nanometre (nm) semiconductors by 2027 and, subsequently, 1.4nm and 1nm chips. This would put it on a par with other global manufacturers like TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), Samsung and Intel.

Aerial photo taken by a Kyodo News helicopter on March 24, 2025, showing a Rapidus Corp plant under construction in Chitose, Hokkaido.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Hokkaido also aims to add to the 45 data centres spread out across the prefecture as at June 2025.

One facility in the coastal city of Ishikari, 15km from Sapporo, has trail-blazing potential for being Japan’s first zero-emission data centre.

Managed by Kyocera Communication Systems, the site that opened in October 2024 is powered entirely by a nearby commercial offshore wind farm, as well as the company’s own solar panels and batteries.

Site manager Tetsu Ogata said: “We combine the two fluctuating renewable energy sources to cover our needs, and when this is insufficient, we have storage batteries that can fill the gap.”

He added: “This is the first 24/7 carbon-free energy consumption data centre in Japan, and while it’s still very gradual right now, I think this will become a long-term trend as more data centres are built.”

Japanese tech and investment giant Softbank, meanwhile, has announced that its new Tomakomai AI Data Centre, which will open by March 2027, will likewise be fully powered by renewable energy.

All this would arguably be more difficult if there were no national backing for Hokkaido and Sapporo to establish a clear niche for themselves.

Japan is targeting 150 trillion yen (S$1.22 trillion) in public-private GX investment over 10 years from 2023, of which at least 40 trillion yen is earmarked for Hokkaido.

That led to the formation of the Team Sapporo-Hokkaido (TSH) consortium in June 2023, comprising 21 institutions from industry, academia, government and finance.

The consortium identified eight key areas of focus: offshore wind, next-generation semiconductors, data centres, hydrogen, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), battery storage, submarine DC power lines, and cargo ships transporting renewable energy batteries and hydrogen.

Subsequently in June 2024, Japan designated Hokkaido and Sapporo jointly as a “national strategic special zone” for financial and asset management businesses with a GX focus, offering deregulation, tax incentives and streamlined support.

The Sapporo Transnational Expansion and Partnership has since fielded inquiries from more than 200 overseas companies looking to expand into Hokkaido.

To further woo institutional investors and channel capital into sustainable projects, the Hokkaido ESG Pro Bond Market was launched at the Sapporo Securities Exchange in September 2025 as Japan’s first sustainability bond market.

And set to be launched in February 2026 is the SPARX Sapporo-Hokkaido GX Fund, a public-private investment vehicle managed by asset management company SPARX Group, with an ultimate goal of reaching 10 billion yen for start-ups and new innovations.

There is also growing excitement in Hokkaido’s start-up ecosystem. Hokkaido University has been going big on environmental research, with ongoing projects such as the development of a direct air capture coating that can transform concrete into a carbon dioxide absorber, with commercialisation planned for 2026.

Mr Kyohei Fujima, executive director of Startup Hokkaido, speaking at a presentation of the efforts by Japan’s northernmost prefecture to incubate and attract start-ups.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

The incubator Startup Hokkaido is now supporting nearly 200 start-ups, mainly in the fields of agriculture, space and energy. Come February 2026, it will host its first global start-up accelerator event, SHAKE-H, a pun on the prefecture’s ambitions to “shake things up” with salmon (sha-ke), the famous seafood catch.

Japan is staking its decarbonised future on nuclear energy, as it fires up atomic plants that were mothballed after the 2011 nuclear disaster at Fukushima. One of the seven reactors at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant – the world’s largest – will be restarted on Jan 20.

Tomari Nuclear Power Plant, which has three reactors, is Hokkaido’s only nuclear facility. Unit 3 was on Dec 10 given the green light to restart by Governor Naomichi Suzuki.

While Japan’s largest prefecture has plenty of space to host more nuclear plants, Hokkaido sees other clean energy sources as playing a far larger role – even if they have run into problems elsewhere.

The island now leads Japan in solar power generation, although mega-solar projects have caused a backlash, given their negative impact on wildlife ecosystems and their destruction of pristine scenery. Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s government has said it will end subsidies for such projects, and instead boost incentives for next-generation solar cells and rooftop solar systems.

While one of the projects that has attracted criticism is a development near the Kushiro Wetlands in eastern Hokkaido, Sapporo’s GX chief, Ms Nishiyama, believes in the need to separate the wheat from the chaff.

The Team Sapporo-Hokkaido consortium, she said, does not back such mega solar projects that are deemed to harm the environment, instead only supporting projects with proper environmental impact assessments and which have won local understanding.

Hokkaido also leads Japan in wind power generation, although this has been no small feat.

At Ishikari Bay New Port Offshore Wind Farm, which began operations in January 2024, 14 turbines produce enough electricity to theoretically power 83,000 households. On site are 240 storage batteries to mitigate intermittency.

The plant counts among its clients Kyocera Communication Systems’ zero-emission data centre in the city.

Ms Kumi Sakaida of Green Power Investment Corporation, which oversees the farm, said it took 17 years for the Hokkaido farm to come to fruition, as it had to conduct feasibility tests, overcome regulatory hurdles and woo investors, among other things.

But she said the efforts had been worthwhile. She declined to comment on whether the farm has turned a profit, citing confidentiality.

Yet Green Power’s achievement belies headwinds surrounding wind power after Japanese trading house Mitsubishi Corp pulled out of three planned projects off the coasts of Chiba and Akita prefectures due to swelling material and labour costs. The retreat prompted the government to look at ways, such as subsidies, to help ensure that offshore wind power operators can avoid massive losses.

Ms Sakaida argued that it was necessary to bite the bullet and seek ways to overcome challenges. She said: “Even if there are headwinds, I believe we should make efforts to introduce renewable energy by facing matters outside our control head-on and overcoming them.”

In 2017, Japan formulated the world’s first national hydrogen strategy. But the country has not made much commercial progress on this front, given the universal criticisms that the gas is too expensive to produce and too difficult to store and transport.

Many hydrogen projects, too, are “grey”, with hydrogen generated from methane, which releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Hokkaido, however, is home to multiple “green” hydrogen projects – with the gas produced entirely through clean energy sources.

Japanese industrial gas company AirWater opened a hydrogen refuelling station in the centre of Sapporo in April 2025, which can accommodate large commercial fuel cell vehicles like buses and trucks.

It has a stake in a “hydrogen farm” in the town of Shikaoi, where there are about 100 dairy farms that raise 21,000 dairy cows. The farm converts livestock manure into biogas and then hydrogen, with the residual heat generated in the process used to raise sturgeon and even grow mangoes in winter.

In a separate project, HEPCO runs a 1MW electrolysis facility as a demonstration project to create hydrogen from water using renewable energy. The company intends to scale up and build a 100MW plant that would be the largest in Japan.

Mr Masaya Kobayashi, vice-president of SPARX Green Energy and Technology, with tanks used to transport hydrogen to its clients.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

And SPARX Green Energy and Technology, a subsidiary of SPARX Group, uses a mix of solar power and biogas generated from a nearby waste disposal facility for round-the-clock hydrogen production in Tomakomai.

It supplies the power to a nearby municipal hot spring, and chemical factories, and to heat gyms and showers at Toyota Motor’s Hokkaido factory.

“We are building a supply chain for production, transportation and use, and we are working to strengthen the cost competitiveness of hydrogen,” said Mr Masaya Kobayashi, vice-president of business development at SPARX Green Energy and Technology.

Current production is relatively low, enough to power about 300 households. But he added: “We’d like to transport hydrogen more often, and our operating rate is still below 50 per cent because it’s still a demonstration.”

Tomakomai is also home to an offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) demonstration project, which is Japan’s first such sizeable showcase of a technology regarded by some as critical for carbon neutrality.

The site is managed by Japan CCS, which was set up in 2008 to conduct trial projects for the government. It captured 300,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide generated from an adjacent oil refinery and injected the gas to be permanently stored in geological formations deep beneath the seabed.

“After storage, the gas eventually mineralises,” said corporate adviser Yoshihiro Sawada.

Such injections were conducted between April 2016 and November 2019, with the company still monitoring for anomalies. None has been found so far.

Elsewhere, the company is involved in trials to transport carbon dioxide by ship, as it tries to identify the best conditions for liquefaction, storage and transportation to achieve larger volumes and lower costs.

“For 10 years from fiscal 2014, Japan CCS conducted a survey of potential storage sites offshore from Japan,” Mr Sawada said. “It was estimated that suitable geological formations for carbon dioxide storage exist at 11 locations, with a total capacity of 16 billion tonnes.”

Mr Yoshihiro Sawada (left), corporate adviser and general manager of international affairs, and Mr Jiro Tanaka, associate general manager of international affairs at Japan CCS, a carbon capture and storage demonstration facility in Tomakomai, Hokkaido.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

Among these was a Tomakomai site, which can accommodate the injection of 1.5 million to two million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, and has been earmarked by the Japanese government for a commercialised CCS project.

Still, despite the progress of Hokkaido’s green efforts, stakeholders admit to challenges.

Ms Nishiyama noted that Hokkaido’s weakness is its hitherto lack of large manufacturing industries, which had meant less demand for electricity than other industrial areas.

“We are just at the starting line as compared with other regions around the world,” she said, noting that generating positive momentum was critical for the success of Hokkaido’s GX ambitions.

Mr Hideki Takada, director of the Finance Ministry-affiliated GX Acceleration Agency, is so convinced of Hokkaido’s potential that he made nine trips there in 14 months.

But he was concerned by global trends. He said: “Every day there is negative news somewhere in the world about decarbonisation and sustainable finance, or political backlash against sustainability, or some sort of regulatory fatigue. And then there are rising prices, all of which are making GX projects harder.”

Yet the impact of climate change is increasingly being felt – never as a linear, steady rise in warming but an increase in variability with more frequent and intense episodes of heatwaves, downpours, droughts and other extreme weather events.

“If the temperature rises steadily and in a predictable way, we can somehow adapt. Rather, the variations are getting worse,” said Dr Eiji Goto of the Hokkaido Research Organisation’s Central Agricultural Experiment Station.

He added that his agency was urgently trying to grow cultivars that are resistant to crops and heat, while maintaining quality and yield.

Mr Soga of Domaine Takahiko cannot help but wonder if things will get worse for him.

While Yoichi has gained a reputation for its pinot noirs, newcomers are instead growing grapes for chardonnays and merlots, which can thrive in warmer climates, Mr Soga said.

He has focused solely on producing the best quality pinot noir he can, knowing that diversifying would be too challenging for a small business like his, which makes only 25,000 bottles a year.

“Even if I decide to switch varieties, it is not as if everything can change overnight. Grapevines take three or four years to bear a good harvest,” Mr Soga said, adding that he hopes to learn how other wine-producing regions afflicted with climate change have adapted.

The father of three children aged 15, 12 and six, mused: “No one knows what the future holds. Everyone has to face nature, so it’s important to use intuition – in Japanese, we call it sensitivity – when working with the environment. And this is something that must be passed on to the next generation.”

AloJapan.com