この記事を日本語で読むには(Googleによる自動翻訳)、こちらをクリックしてください。

We need your help! We are dedicated to providing rapid scientific analysis following earthquakes, but to make this effort sustainable, we need financial support. If you can, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you use our Substack as part of a group, or for teaching, consider a teaching or institutional subscription. Every paid subscription makes a real difference — and unlocks access to the more than three hundred posts in our archive!

Free subscribers still get all of our new posts by email, and all of our posts are free to read for one month. If you have recently lost your job or are a student or researcher without ability to pay, let us know and we will upgrade your subscription to “paid” at no cost.

Also: check out our recent interview with Dr. Shawn Willsey, where we talk about our geological backgrounds and how we ended up here, writing Earthquake Insights!

At 10:18 local time on January 6, 2025, a magnitude 5.7 earthquake struck southwestern Japan, near the border between Shimane and Tottori prefectures.

The earthquake was felt across most of southern Honshu, as well as Shikoku and Kyushu islands. The strongest shaking reached JMA intensity 5+, which is equivalent to MMI VII. That is strong enough to topple unsecured furniture and cause collapse of unreinforced concrete walls.

News reports indicate several injuries, toppled gravestones, and one possible collapsed stone wall blocking a road. JMA also highlights that long-period motion occurred. Long-period motion is a slower, back-and-forth swaying, compared to the rattle of shorter period motion, and can be felt especially strongly on the higher floors of tall buildings. In addition to the general increase in swaying on higher floors, buildings of different heights have different natural resonant frequencies, which can significantly increase motions. The following video is a classic demonstration of how earthquake frequencies can resonate with buildings of different heights, with long-period motions affecting tall buildings in particular.

The Japanese Meteorological Agency is reporting the event as magnitude 6.2, and many news reports have adopted that number. It is quite common for different earthquake agencies to report slightly different magnitudes for the same earthquake, due to differences in seismic networks and methodologies. Earthquakes are complicated, and there are a lot of different ways to reduce them to a single number. However, a gap of 0.5 magnitude is larger than usual.

The higher number from the Japan Meteorological Agency is on a different magnitude scale (MJMA) than the lower moment magnitudes (Mw) of 5.7-5.8 reported by various international organizations. While all magnitude scales capture some aspects of the “size” of an earthquake, they vary because they are measuring different frequencies of shaking at different distances from the hypocenter. A difference of ~0.5 magnitude between Mw and MJMA is within the range of normal. For instance, the 2018 Osaka earthquake was reported as Mw5.5/MJMA6.1, and the 2000 Tottori earthquake, which occurred very close to the recent earthquake, was Mw6.7/MJMA7.3.

All of this is just to say that it is correct to report the event as M5.7, and also correct to report it as M6.2. However, it is important to compare apples to apples — for instance if you wanted to compare this recent earthquake to the 2018 Osaka earthquake, you should stick to either Mw or MJMA, rather than mixing. (Both would tell you that the Osaka earthquake was slightly smaller.) Ultimately, the impacts of an earthquake depend more on its location, the population density, and the vulnerability of structures than on the magnitude.

Ok, enough with the technical stuff. What’s going on in the crust beneath this part of Japan, tectonically speaking? The answer, it turns out, is pretty fascinating.

We usually start our analyses from a big-picture perspective and zoom in. This time we are going to reverse that process, looking at details and then zooming out and extending our time window to see the bigger story.

Let’s start with this one earthquake sequence using data from the publicly available JMA earthquake catalog. Because Japan operates a very dense seismic network, events in this catalog are much more accurately determined, and extend down to much smaller magnitudes, than global catalogs. For the plot below, we have altered our usual magnitude scaling for the earthquake symbols in order to emphasize the particularly small events (M~0-2). (Usually these events are plotted much smaller, to reflect the fact that they release very little energy.) The earthquakes here are colored by time, since December 28, 2025 — so we’re looking at a little more than a week.

Figure 2: Seismicity since December 28, 2025, colored by time and projected to the right onto a timeline. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Figure 2: Seismicity since December 28, 2025, colored by time and projected to the right onto a timeline. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Interestingly, this earthquake had a clear foreshock sequence, with a number of magnitude 0 to 2 events occurring in one location near the eventual hypocenter, over the six days leading up to the mainshock. Over the day prior to the mainshock, the magnitude of the foreshocks increased into the magnitude 2 to 3 range. This looks like an interesting cascade-up type sequence; perhaps some future studies will eventually examine the details.

If we now return to our usual magnitude scaling and adjust our zoom level, we can see that the aftershocks are scattered in the east-west direction over a distance of about 8-9 kilometers, implying that rupture mainly happened on a roughly east-northeast (ENE) trending fault. At the very western edge of the aftershock zone, there is also a faint indication of a more north-northwest (NNW) trend; we have drawn a question mark to indicate that this pattern is pretty speculative. Note that the foreshocks are still on this map, but are almost too tiny to see!

Figure 3: Earthquake sequence associated with the 2026-01-06 M5.7 earthquake. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Figure 3: Earthquake sequence associated with the 2026-01-06 M5.7 earthquake. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

These epicenter trends both nicely match with the USGS focal mechanism for the earthquake, which indicates almost pure strike-slip faulting on a vertical structure oriented either ENE or NNW:

So, we have a first guess about a fault orientation. The main action appears to be right-lateral slip on a ENE-oriented strike-slip fault.

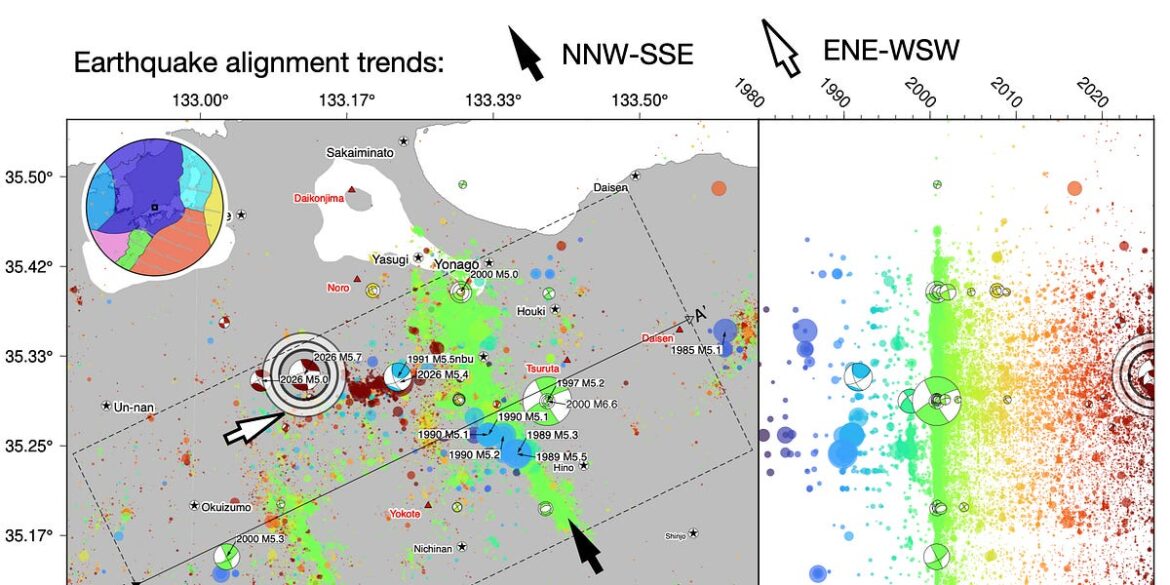

Next, let’s zoom out a bit and expand our time range to earthquakes since 1980. On this map, focal mechanisms are from a variety of sources, preferring USGS solutions. The locations of geologically recent (Pleistocene and Holocene) volcanoes from the Smithsonian volcano database are also indicated as red triangles, labeled with red text — that will become important later. On this map, the earthquakes are colored by time since 1980.

Figure 5: Seismicity since 1980 around the recent M5.7, colored by time. Black and white arrows point out alignments in the NNW-SSE and ENE-WSW directions, respectively. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Figure 5: Seismicity since 1980 around the recent M5.7, colored by time. Black and white arrows point out alignments in the NNW-SSE and ENE-WSW directions, respectively. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Our recent earthquake and its aftershocks (darkest red symbols) reveal a structure that is just one part of a complex system of active faults. The focal mechanisms show that the earthquakes here are all varieties of strike-slip, but the aftershock clouds clearly indicate that previous recent large events have mostly activated north-northwest (NNW) trending structures. The 2000 M6.6 Tottori earthquake left a 20 kilometer long blaze of aftershocks (bright green on the map), and also activated a second NNW-trending structure farther west. In 1989, 1990, and 1991, other M5+ earthquake struck along the same alignment.

Squinting hard, we can maybe see a ENE-trending alignment in the blue dots, right near the location of the most recent earthquake.

Let’s take a different view of the structure of these active faults by examining a cross section, A-A’ on the figure above. To aid interpretation, we have added some annotations.

Figure 6: Cross-section of seismicity; see Figure 5 for location.

Figure 6: Cross-section of seismicity; see Figure 5 for location.

First, note that the older earthquake data (blue dots) look much shallower than the more recent data. This is not because earthquakes have moved deeper over time; it is because the older seismic networks could not resolve the event depths very well. So, we can ignore the depth information of those events. Their locations on the map are also more scattered, for the same reason.

In general, the seismicity in this region is mainly restricted to depths less than 15 kilometers. Below that depth, the crust is just too hot to break in brittle failure, under typical stressing conditions. Instead, rocks within shear zones inside the deep crust deform slowly over time as mineral grains smear out and recrystallize, relieving stress without earthquakes. The depth of this mechanical transition is creatively called the maximum seismogenic (earthquake-making) depth.

There is one notable exception to this pattern: an oblong cluster of earthquakes deep within the crust, at a depth of about 30 kilometers. This cluster plots in the lower crust, fairly close to the estimated depth of the crust-mantle boundary, called the Moho. (The Moho was named after its discoverer, Andrija Mohorovičić, but most people seem content to abbreviate.)

In our dataset, the cluster appears to start right after the October 2000 earthquake sequence. However, this is a case of caveat emptor. The HiNet network itself seems to have been established in October of 2000, so the apparent onset probably just reflects the time when the network could begin to sense these very small earthquakes. That is quite a coincidence, and is a good example of how catalog issues can masquerade as tectonic signals!

Figure 7: The deep earthquake cluster, in map view and over time. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Figure 7: The deep earthquake cluster, in map view and over time. Earthquakes are from the JMA catalog.

Fortunately, that earthquake cluster has already been identified and studied. Aso and Ide (2014) examined low-frequency earthquakes (LFEs) associated with this cluster, and found that they were similar in nature to volcanic LFEs. Aso and Tsai (2014) attributed the strange seismic features of these events to cooling of deep, stalled magma.

That seems like a bit of an aside, but the role of magmatism might be quite important for earthquakes here, as we will discuss in a moment.

Finally, the seismic profile two figures above also shows a dramatic lack of earthquakes at the shallowest crustal levels, within 3-5 kilometers of Earth’s surface. This is typical of crustal seismicity in many other well-instrumented areas, such as California. A likely explanation is that the rocks of the shallow crust are just too broken up and too gently compressed under their own weight to sustain stick-slip behavior, so any tiny earthquakes just can’t grow up to sensible size. After the 2000 M6.6 Tottori earthquake, distributed cracking was observed at (and near) Earth’s surface along the fault zone, but no continuous surface rupture formed. How, and whether, the active faults in this area actually reach the surface is certainly another interesting question.

Zooming out once showed us that the small-scale features of one rupture seem to reflect the features of a larger area. What will we see when we zoom out further? On the map below, seismicity is colored by time since 1900.

Figure 8: A further zoomed-out map and timeline of seismicity.

Figure 8: A further zoomed-out map and timeline of seismicity.

Our map area is now 200 kilometers wide. Seismicity generally follows the coast, and also generally follows the trend of volcanoes. The January 6 earthquake falls right smack in the middle of this earthquake band.

Once again, we see alignments in both directions (black arrows show NNW-SSE alignments, white arrows are next to, or pointing at, ENE-WSW trends). There is clearly a fractal organization of faults in this region, similar at all scales.

This particular earthquake region is called the San-in Shear Zone. We have already used the term ‘shear zone’ earlier, to indicate regions where plastic strain is accommodated in the deeper crust. However, the term can also apply to a region of crust where brittle faulting is distributed onto many different structures. Not confusing at all.

Let’s plot a cross section along the San-in Shear Zone:

Figure 9: Another cross-section of seismicity, see Figure 8 for location.

Figure 9: Another cross-section of seismicity, see Figure 8 for location.

As before, the maximum seismogenic depth is about 15-20 kilometers, and the earthquakes are mostly occurring on ENE- and NNW-oriented strike-slip faults. So, the January 6 earthquake seems entirely consistent with the regional tectonic picture.

But what is that regional picture anyway? Why does this brittle shear zone exist? What does it connect to? Let’s zoom out once more.

In general, the seismo-tectonics of Japan are dominated by its two subduction zones: the Nankai Trough, where the Philippine Sea Plate is colliding with (and sinking beneath) the crust of southern Japan at a rate of about 6 centimeter per year, and the Pacific Plate, where the Pacific Plate is colliding with (and sinking beneath) northern Japan at about 10 centimeters per year.

Figure 10: Focal mechanisms of earthquakes across southern Japan, colored by depth.

Figure 10: Focal mechanisms of earthquakes across southern Japan, colored by depth.

Most earthquakes in Japan are directly related to these two subduction zones, occurring on the megathrust faults that separate the plates, within the subducting slabs themselves, or in close proximity.

However, many earthquakes in Japan don’t occur close to the subduction zones at all. All of the earthquakes we have been discussing, in southwestern Honshu, fall into this category. The 2024-01-01 M7.5 earthquake in Noto, Japan is another example (also marked on the map above).

While these earthquakes are not co-located with the subduction zones, they are still directly linked to the overall tectonic setting: oblique tectonic convergence. Exactly how the tectonic stresses are accommodated as earthquakes along faults depends on what kinds of crustal weaknesses there are (for instance, faults that formed at previous times, geological discontinuities, and volcanoes), but the driving forces mostly still come from that incremental movement of the plates.

One of the ways that we can see this is by looking at how the earthquakes are accommodating crustal movement. Although the 2024 Noto earthquake and the recent M5.7 earthquake reflect different styles of slip (Noto: thrust; recent M5.7: strike-slip), both events represent a component of northwest-southeast convergence. At Noto, the convergence is simply a shortening of the crust. To the southwest, where the recent earthquake occurred, the combination of orthogonal faults allows a reorganization of the crust with shortening in the WNW-ESE direction, combined with stretching in the perpendicular NNE-SSW direction. In both cases, the shortening direction is similar to the overall motion of the subducting plates relative to Japan.

Figure 11: Like Figure 10, but with arrows highlighting the general convergence accommodated by the earthquakes in western Japan.

Figure 11: Like Figure 10, but with arrows highlighting the general convergence accommodated by the earthquakes in western Japan.

So, why are there active faults in the San-in Shear Zone anyway? This kind of ‘why’ question is often quite fraught, but it is certainly fun and interesting to think of possible explanations.

We are aware of two hypotheses, presented in recently published papers. One explanation calls on ancient crustal structures reactivated by present-day stresses, and the other calls on unique geological conditions of the region.

First, Uchida et al. (2021) noted that the active faults in the San-in Shear Zone don’t really appear at the surface as clear structures, but are instead similar in orientation to small-scale faults and fractures that can be mapped in bedrock exposures. Those small-scale faults mostly originated during the original opening of the Japan Sea, long ago. As the crust of Japan has deformed and rotated over time, and as the tectonic stress directions have changed, these old fractures have been reactivated once again as strike-slip structures. Because these old faults are pervasive through the crust, and because the shear zone itself has not been around very long, the fault system is still extremely distributed.

Figure 12: One possible model showing how the San-in Shear Zone evolved. Ancient faults rotated into a new shear zone and were reactivated. Figure 8 of Uchida et al. (2021).

Figure 12: One possible model showing how the San-in Shear Zone evolved. Ancient faults rotated into a new shear zone and were reactivated. Figure 8 of Uchida et al. (2021).

An entirely different explanation presented by Shibazaki et al. (2025) relates the active faults to zones of crustal weakness along the volcanic arc. The basic idea is that rising magmas heat the crust in a few areas, greatly weakening those areas and allowing the crust there to rapidly deform when stressed. The left-over strong areas in between the weak zones instead concentrate stress and are forced to fracture, creating a fault network with a non-intuitive, but mechanically explainable, geometry. This model predicts that the faults are geologically very new, and formed in situ under the present stress conditions.

Our favorite figure from the Shibazaki et al. (2025) paper is this one, showing a measurement of the maximum seismogenic depth, as mapped out by the earthquake data:

Figure 13: Seismogenic depth across the San-in Shear Zone. Figure 10 of Shibazaki et al. (2025).

Figure 13: Seismogenic depth across the San-in Shear Zone. Figure 10 of Shibazaki et al. (2025).

The blue and green areas have a deeper seismogenic depth, indicating colder crust. The yellow and orange areas have a shallower seismogenic depth, largely coinciding with the volcanic arc (red triangles). The visual coincidence of these mysterious, strangely oriented strike-slip faults with the areas of hotter crust is indeed quite compelling! So maybe there is a good mechanical explanation for the faults.

We will end by pointing out a paper, Lythgoe et al., 2021, that Kyle co-authored (and made the figures for, believe it or not using Matlab). That paper looked at two large earthquakes that occurred beneath a huge volcano in Indonesia. The aftershock patterns of those events indicated that the massive heat stored in the crust beneath the volcano helped to control the area of the thrust fault that ruptured. Whether the thrust fault formed in this particular location due to the effect of the volcanic arc was not directly addressed.

Figure 14. A perspective view of Gunung Rinjani, Lombok, Indonesia, from Lythgoe et al. (2021). Aftershocks of two large earthquakes show strong depth variation beneath the volcano, limiting the area of the Flores Thrust that could rupture.

Figure 14. A perspective view of Gunung Rinjani, Lombok, Indonesia, from Lythgoe et al. (2021). Aftershocks of two large earthquakes show strong depth variation beneath the volcano, limiting the area of the Flores Thrust that could rupture.

So, there is clearly a lot going on in this part of Japan, much of it quite interesting. If anyone has further information about this unusual shear zone or the deep cluster of seismicity, or has corrections or objections, please leave a comment below!

Aso, N. and Ide, S., 2014. Focal mechanisms of deep low‐frequency earthquakes in Eastern Shimane in Western Japan. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 119(1), pp.364-377. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JB010681

Aso, N. and Tsai, V.C., 2014. Cooling magma model for deep volcanic long‐period earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 119(11), pp.8442-8456. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011180

Dalguer, L.A., Irikura, K. and Riera, J.D., 2003. Generation of new cracks accompanied by the dynamic shear rupture propagation of the 2000 Tottori (Japan) earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 93(5), pp.2236-2252. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120020171

Li, Y., Wang, D., Xu, S., Fang, L., Cheng, Y., Luo, G., Yan, B., Enescu, B. and Mori, J., 2019. Thrust and conjugate strike‐slip faults in the 17 June 2018 MJMA 6.1 (Mw 5.5) Osaka, Japan, earthquake sequence. Seismological Research Letters, 90(6), pp.2132-2141. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220190122

Lythgoe, K., Muzli, M., Bradley, K., Wang, T., Nugraha, A.D., Zulfakriza, Z., Widiyantoro, S. and Wei, S., 2021. Thermal squeezing of the seismogenic zone controlled rupture of the volcano-rooted Flores Thrust. Science Advances, 7(5), p.eabe2348. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe2348

Shibazaki, B., Nishimura, T. and Matsumoto, T., 2025. Modeling the San-in shear zone in southwest Japan: development of the immature shear zone along the volcanic front. Earth, Planets and Space, 77(1), p.182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-025-02306-6

Uchida, H., Mukoyoshi, H., Tonai, S., Yamaguchi, M. and Kobayashi, K., 2021. Reactivation of minor faults in a blind active fault area: A case study of the aftershock area of the 2000 Western Tottori Earthquake, Japan. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences: X, 5, p.100053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaesx.2021.100053

Wald, D.J., 2020. Practical limitations of earthquake early warning. Earthquake Spectra, 36(3), pp.1412-1447. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755293020911

AloJapan.com