This is an audio story from Eos, your trusted source for Earth and space science news. Do you like this feature? Let us know in the comments or at [email protected].

TRANSCRIPT

Emily Gardner: Justin Higa is a geologist, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he studies landslides.

But like most of us, he does more than just work. He has hobbies. When he was in high school, he started taking lessons on the sanshin, a three-string lute that has been called “the soul” of the music tradition in the Ryukyu Islands, a chain of southern Japanese islands that include Okinawa. Higa himself is Okinawan, and he wanted to learn more about his culture. So he joined the Ryukyu Koten Afuso Ryu Ongaku Kenkyu Choichi Kai USA, Hawaiʻi Chapter. His instructor was June Uyeunten, or, as he calls her, June Sensei.

At AGU’s Annual Meeting in New Orleans this December, Higa presented research that aimed to bridge the worlds of geoscience and Indigenous Ryukyuan music.

Justin Higa: This started because when I was an undergrad at the University of Hawaiʻi, there was a lot of focus on place-based science and Indigenous Knowledge and Hawaiian knowledge in geology. So because of this background in the arts that I had, and I knew that we’d sung songs about nature and animals and plants, I thought, “Oh, you know, we could do similar things with the songs that we sing and interpret science from lyrics.”

Gardner: Higa went to California for grad school, but when he came back to Hawaii for his postdoc, he had a little more freedom to pursue different research interests, and he was back in a place with a strong Okinawan diaspora presence. Maybe he could use this music to teach the public, and people interested in music, about the geosciences. His mentor, Uyeunten, was excited for the inverse reason: Maybe this could be a way to get the public, and scientists, interested in Ryukyuan music.

June Uyeunten: I got superexcited, cause I’m like, if Justin can get that excitement out into the public, maybe we can tap other people who are not interested in this type of music to learn more about it, right? And so you don’t know which audience we’re going to appeal to. And so we just have to try different ways to educate others. And music is universal. You don’t need to understand the lyrics, but you could feel it when a performer sings it, right?

Gardner: Higa teamed up with Uyeunten and Kenton Odo, who are both instructors in the same chapter, to look at how Indigenous Ryukyuan music could be used to teach about geoscience and the climate.

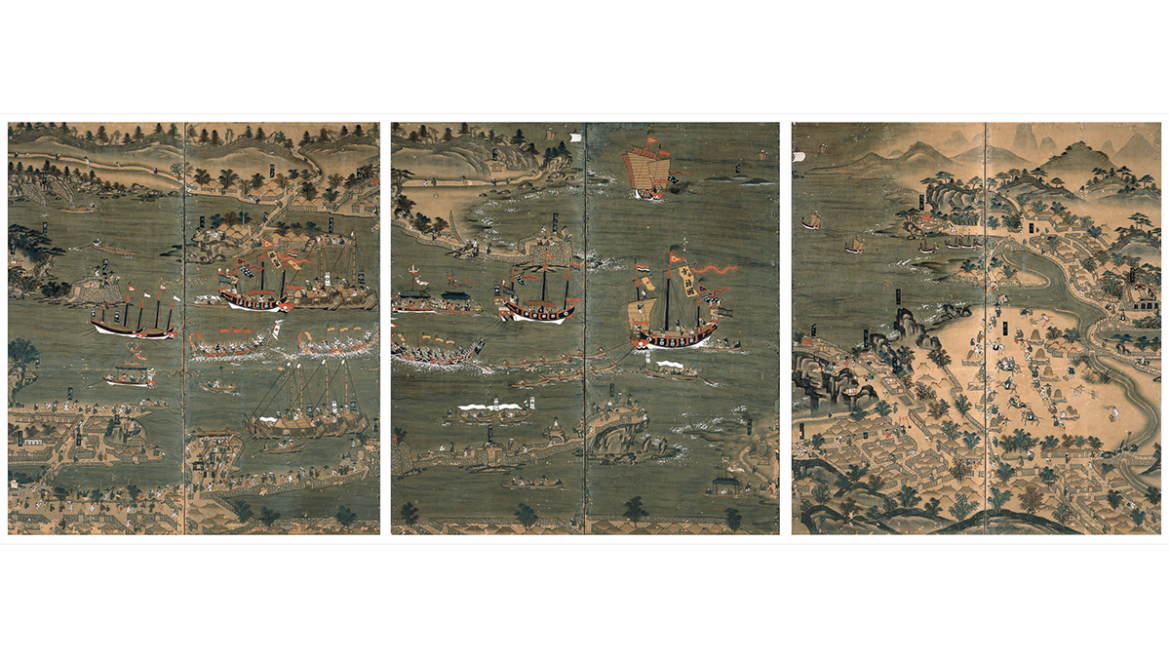

They focused their analysis on a pair of sailing songs, both composed in the 18th century. One is called “Nubui Kuduchi”; Kuduchi is a subgenera of Ryukyuan classical music. And nubui means “climbing up.” The song starts with a description of a group of envoys walking from the Ryukyu capital to the main port on Okinawa, stopping at temples along the way to pray, and then saying goodbye to their families. Then, they set sail to the Kyushu islands:

(sample of “Nubui Kuduchi” plays)

The lyrics here say, “Sailing across the rough seas off the coast of Iheya, we look out over the route of many islands. To see the Tokara Islands and Strait, and pass without mishap. How lucky we are.”

The south-southwesterly winds described in the song, taking place between May and September, match with observations from the 20th and 21st centuries, which have documented the same wind patterns at the same time of year. The researchers further looked at historical records, which showed that during this period of history, about 20 such envoy departures took place each year between approximately May and August. It all lined up perfectly.

They also analyzed another song called “Kudai Kuduchi.” Kudai means “climbing down.” In this song, the envoy returns to Okinawa island via north-northeasterly winds.

(sample of “Kudai Kuduchi” plays)

The lyrics here say, “The winds are directly from the north-northeast, with Cape Sata behind us. Sailing comfortably over the seas of the Tokara Islands and Strait.”

Once again, it all lines up: The northeasterly boreal winter monsoon typically occurs from September to May, and historical records show the envoys returning to port at that time of year.

Higa: We could make implications and a discussion about how this kind of implies a reliance on a very constant monsoon season for travel, and when that breaks down, that’s a problem for them.

Gardner: In another line, the sailors observe an active volcano.

Higa: It’s kind of cool in that this volcano that they observed as active during their boat journey, it was kind of in a location that’s a little outboard from the main Japanese islands that had a lot of written historical records.

So maybe the earliest record was from, I think the 12th century, and then we have our song from the 18th century and then modern instrumented science. So it’s these three points of volcanic activity and ours is kind of bridging that in the middle, kind of implying that, yeah, this volcano has been active for continuously for a very long time and that aligns with geochronologic dating, geologic mapping of this area.

Gardner: James Edwards is an ethnomusicologist at the SINUS Institute, an institution for market and social research in Germany. He wrote his dissertation on the Okinawan performing arts, tracking its development from the 17th century to today. He focuses in part on ecomusicology, a field that examines, among other things, how music mediates the relationships between humans and the environment.

Edwards was not involved in this work, but he said the project was really interesting and could be a launching point for potential interdisciplinary collaboration.

James Edwards: Traditional ecological knowledge can be a valuable intervention contra the overreach of Western scientism and the privileging of Western knowledge systems, right? In this case, you have the opposite. You have a traditional ecological system and Western scientific knowledge synergizing and complementing each other in a really beautiful way.

Gardner: On top of the research presented at AGU25, the authors have published a paper about their work in Geoscience Communication and shared the work in the science and art worlds, including at the Geological Society of America conference and an Okinawan festival in Hawaii. September of 2025 marked 125 years since the first Okinawan immigrants arrived in Hawaii. Especially during such a landmark year, Higa and Uyeunten have high hopes for the work. Incorporating such music into science lessons, for instance, could help educators demonstrate the value of Indigenous Knowledge throughout history.

Uyeunten: If you can blend your career with your culture and with some art form, I think that’ll just, you know, be a good thing to just broaden everyone’s lenses.

Higa: I guess it, I hope it really shows the legitimacy of Indigenous Knowledge from all cultures and it inspires other people to….think of themselves as you can be a scientist and you can be an artist.

(“Kudai Kuduchi” fades in)

Gardner: Thank you to Justin Higa and June Uyeunten for speaking with me and to their coauthor, Kenton A. Odo. All are members of Ryukyu Koten Afuso Ryu Ongaku Kenkyu Choichi Kai USA, Hawaiʻi Chapter. Thank you also to James Edwards for providing an outside perspective. Credits for the music are as follows:

Translation and interpretation: Hooge Ryu Hana Nuuzi no Kai Nakasone Dance Academy, Clarence T. Nakosone

Singing and Sanshin by Kenton Odo

Tēku (the drums) and fwansō (the bamboo flute) by June Uyeunten

Thanks for listening to this story from AGU’s Eos, your source for Earth and space science news. As always, you can find a transcript of this story, as well as links to the relevant research, at Eos.org.

—Emily Gardner (@emfurd.bsky.social), Associate Editor

Citation: Gardner, E. (2025), What Okinawan sailor songs might teach us about the climate, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250486. Published on 22 December 2025.

Text © 2025. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.

Related

AloJapan.com