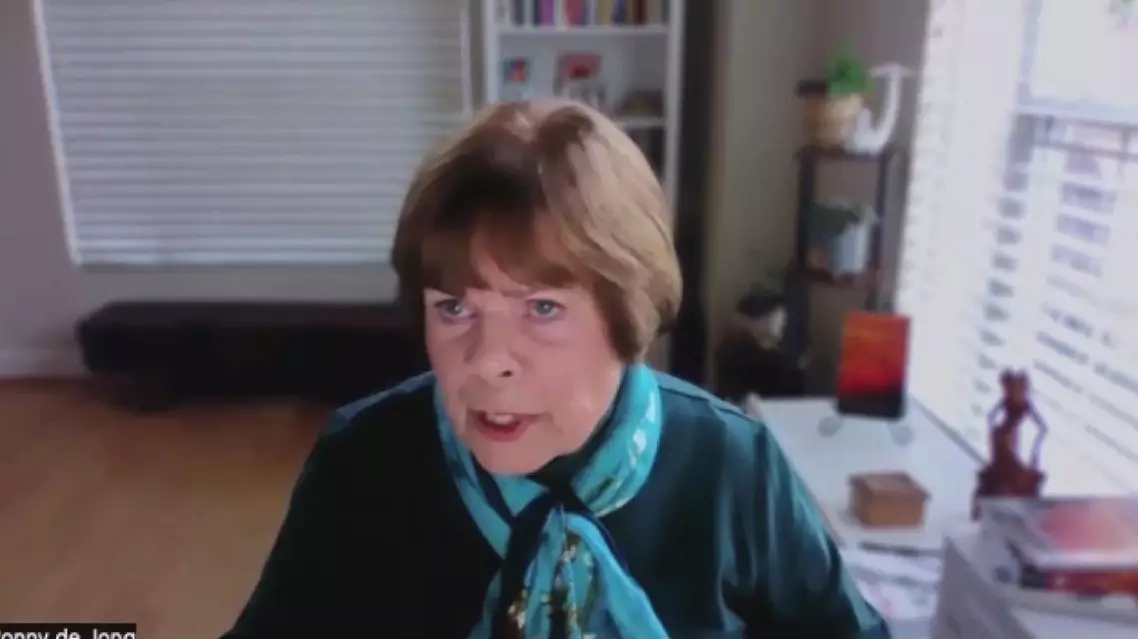

Ronny Herman de Jong, a Dutch-American survivor of Japanese-run internment camps in Southeast Asia during World War II, has recounted the atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army against women and children, urging the Japanese government to issue a formal apology to the victims and survivors.

Born in 1938 on the island of Java in the then Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), de Jong was just a toddler when Japanese forces invaded in 1942.

Along with her mother and younger sister, she was forcibly interned in a concentration camp for women and children, where they endured nearly four years of starvation, disease, and brutal treatment, narrowly escaping death on multiple occasions.

“In the women’s camps, they would put bamboo sticks under the fingernails. They put burning cigarette butts on women’s breasts. That did not happen to my mom, but it happened to a lot of the people. They were severely maltreated. Even little babies were just killed. In the end, there were so many deaths. The mortality rate on Java [Island] was more than 10 times normal, and there were no longer coffins provided anymore. People that died just had to be taken out of the camp and dumped into a big pit that the women had to have dug, or they were just dumped over the fence,” de Jong recounted.

After the war, her family emigrated to the United States. Decades later, she published a book based on her mother’s secret diary — smuggled out of the camp — which chronicled their harrowing ordeal.

First released in Canada in 1992, the book met with significant resistance in Japan. According to de Jong, a Japanese journalist in Canada who had agreed to translate the work was later murdered, halting efforts to bring the account to Japanese readers.

To this day, de Jong stressed that Japan has never issued a formal apology to the victims or survivors of its wartime aggression across Asia.

“Japan has never offered an apology to any of the survivors or victims. Now, Japan is starting to change their democracy by changing that Article 9 [of the Japanese Constitution] that says Japan should not have any armed forces ever again that can start war. And now, the [Japanese] prime minister is trying to change that by reinforcing the Japanese arms,” she said.

In 2001, de Jong realized how little the world knew about the Japanese-run internment camps in Southeast Asia during WWII. Declassified documents from the U.S. National Archives revealed a chilling plan: Japanese authorities had intended to systematically exterminate all remaining camp internees beginning in September 1945, just weeks after Japan announced its unconditional surrender.

Since then, de Jong has dedicated herself to compiling testimonies from WWII veterans and former child internees, publishing more books to ensure this history is never forgotten nor denied.

“What I want to say to the generations of now and to come, you have to remember this war — the Second World War in the Pacific. It was the most cruel and expensive war ever. That is not a war that you can say ‘oh, it did not happen’. It does not. That is not true. You have to remember this war,” she said.

Concentration camp survivor recounts Japanese army’s atrocities during WWII

The latest border conflict between Thailand and Cambodia is disrupting livelihoods of fishermen in Trat Province of Thailand, even far from the front lines.

As tensions flare along the Thai–Cambodian border, the Royal Thai Navy has ordered a temporary suspension of fishing in Trat Province, grounding local fishermen as tensions spill from land into Thailand’s eastern waters. Naval patrols now crisscross familiar fishing grounds, and once-routine routes have become potential flashpoints.

For Trat’s coastal communities, the economic toll is immediate.

“Since the recent outbreak of clashes along the Thai–Cambodian border, security officials have introduced measures asking for cooperation to prevent fishing boats from going out to sea. This group of people has been affected — they can’t go out to earn income. We’re concerned about this as fishermen have no income, yet they still have debts,” said Attpol Arunwuttipong, secretary of the Trat Chamber of Commerce.

Local fishermen said that for them, fishing is not just a livelihood, but a daily economy. Along the pier, the change is unmistakable. Piers that once throbbed with pre-dawn shouts, and the thud of fresh catch now sit eerily silent.

“The number of fishing boats has decreased by about 40–50 percent compared to before [the outbreak of the conflict]. The current situation is that only around 10 local boats remain, just circulating in and out. The labor force has also disappeared, with about 60–70 percent returning to their hometowns,” said Pakdee Siri, who works at a fishing pier.

The restrictions and the conflict are also rippling through Trat’s local markets. Vendors who normally lay out rows of fresh fish, squid and crabs now have little to sell, or nothing at all. Their customers are also all gone — to evacuation shelters, or just too scared to leave their houses.

“There are no customers. I bring in shrimp but can’t sell them. From selling almost 100 kilograms a day, it’s now down to just about 20 kilograms. If there is no shrimp, this market would have almost nothing to sell. There’s no fish either, because the boats aren’t allowed to go out, so there’s nothing,” said Srinual Saowanee, a seafood vendor.

Border clashes between the two sides reignited on Dec 7, less than two months after the two sides signed a joint peace declaration, with both sides trading the blame for instigating the attacks.

Border tensions harm fishermen’s livelihoods in Thai province

AloJapan.com