A business trip to New York and Washington drives home the price gaps now in place between America and Japan, prompting thoughts about Japan’s policy choices helping to bring them about.

A Pricy Trip to the States

During a recent business trip to the United States, I found myself shocked—not for the first time in recent years—by the price differences between Japan and the United States. As I had done often before, I woke up early the next morning after arriving in New York in early November and eagerly headed to Barney Greengrass, a long-established and popular bagel shop known for its affordable but delicious food.

The first thing that hit me and my business companion was the $2.90 subway fare. Using an exchange rate of ¥154 to the dollar, that came to nearly ¥450—around 2.5 times the price for a short-range subway trip in Tokyo.

A smoked salmon and cream cheese bagel. (© Katō Izuru)

When we arrived at the restaurant, there was already a long line. Following a 15-minute wait, we were seated at a sidewalk table. We copied the orders of the local regulars and eventually got a bagel with smoked salmon and cream cheese, scrambled eggs sautéed with salmon, latkes (Eastern European–style potato fritters), and coffee.

Without a doubt, we were satisfied with the quality and taste. However, after adding the 20% tip and tax, the bill came to the equivalent of more than ¥7,000—the price of a morning buffet on the top floor of a first-class hotel in Tokyo. With the faint scent of truck exhaust wafting by us as we sat outside, this wasn’t exactly a fine dining experience. But sadly, we paid fine dining prices here, as we did at many other of New York’s previously affordable local eateries.

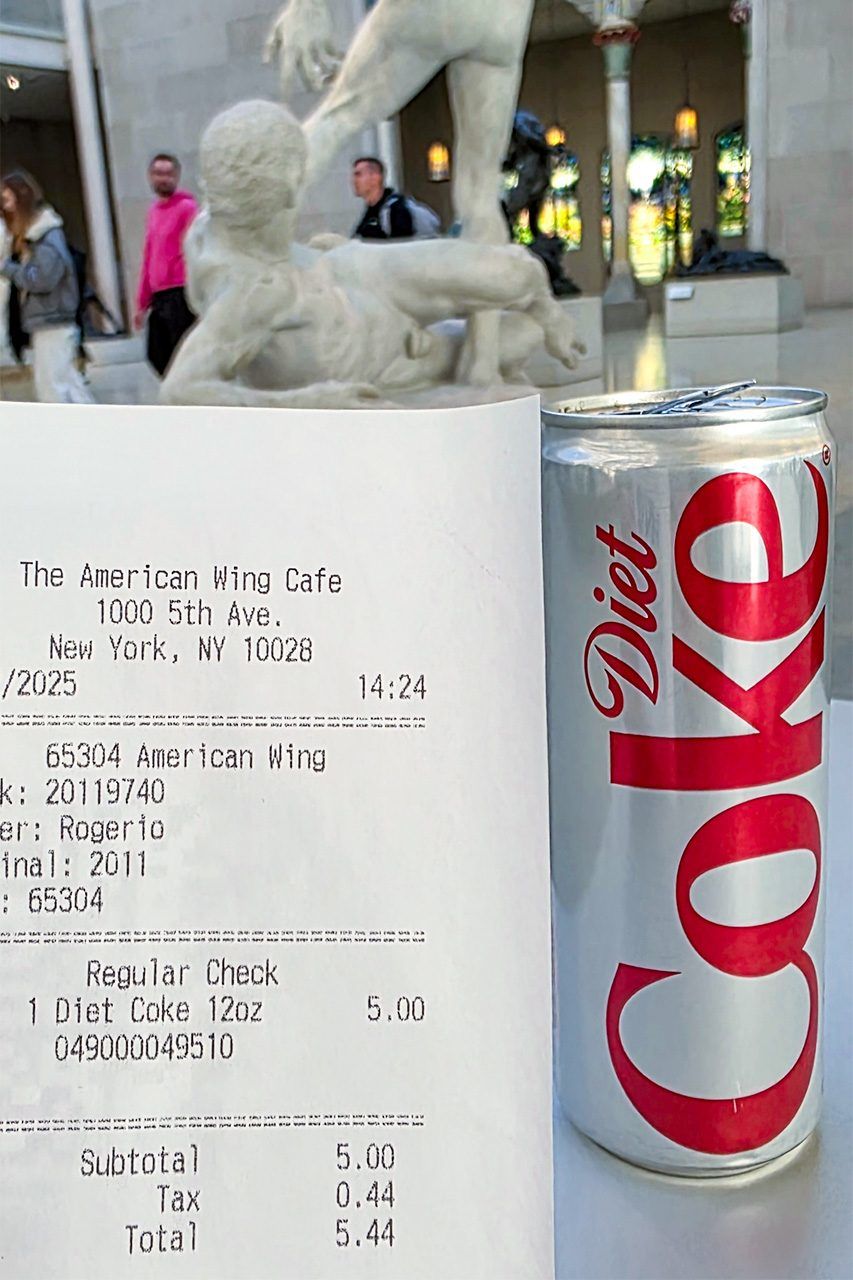

The ¥800 Self-Service Diet Coke

My humble drink, with anything but a humble price. (© Katō Izuru)

I also got a nasty surprise at a self-service cafe in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jet-lagged with a foggy brain, I grabbed a Diet Coke and used contactless payment without looking at the price. When I sat down, I finally looked at the receipt: $5.44 (more than ¥800)!

The Japanese chain restaurant Ōtoya has a store near New York’s Times Square. Known in Japan for serving “home style” teishoku (set meals), I decided to try it for the first time in a while. I ordered shima-hokke (Atka mackerel) in a set meal with grated yam (tororo) on the side. Worn out from the overseas trip, it definitely did the trick for my stomach to eat something familiar. However, the total cost came to north of ¥7,000, including tip and tax. The same order at Ōtoya in Tokyo would cost ¥1,240, making this 5.8 times more expensive.

Looking around, I also did not see any of the Japanese residents and their families who used to frequent Ōtoya in large numbers before. Instead, the place was bustling with non-Japanese residents, and was basically full.

What about other famous New York activities, like Broadway? Checking the ticket prices on the official website, the best seats at a weekend evening performance of The Lion King in late December (the peak season) would put you back around ¥65,000. In Tokyo, the highest-priced seats for the same show are five times cheaper, at ¥13,000.

Moving on from New York, at a Washington DC drugstore I purchased a regular-sized turkey sandwich on sourdough. This was admittedly a little larger than the standard sandwich size in Japan, where it might cost around ¥400 in a convenience store, but here, it was $10.60 (¥1,600).

My Ōtoya set meal (left) and the Washington DC turkey sandwich. (© Katō Izuru)

I stepped into a small, likely independently run souvenir shop. The owner soon asked, “Are you Japanese?” He had just returned that very morning from Osaka after a two-week trip to Japan.

He told me that he thoroughly enjoyed himself: “Japan is amazing! Everyone is so kind, there are no homeless people. Prices are incredibly cheap. I couldn’t believe a delicious lunch cost only five or six dollars! I definitely want to go again!”

While it’s nice to hear praise for Japan, it is clear that many countries now perceive Japan as “cheap.” Perhaps we are selling Japan’s quality cultural products far too cheaply?

Extreme Yen Depreciation

One of the major reasons for such a wide gap in price levels is persistent inflation in the United States. According to estimates by GOBankingRates, the minimum annual income required to live comfortably in New York is ¥28.4 million, while the figure is ¥24.33 million in Washington DC. The highest level is ¥40.8 million in San Jose, California, in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Another, perhaps even more consequential, cause is the extremely weak yen. If you look at the purchasing power of the yen and dollar against the actual exchange rates, it is clear that the current yen is significantly undervalued. We have to go all the way back to 1970, when the exchange rate was ¥360 to the dollar, to see similar levels of undervaluation.

In other words, Japanese visiting the United States will now be astonished just like Japanese people visiting the United States were over half a century ago, when people were still debating whether Japan should be considered a developed country. Meanwhile, currencies like the euro, British pound, and Australian dollar are not undervalued quite to the same extreme extent as the yen. A tourist from any of those countries would not perceive American prices to be as high as Japanese would.

Ultimately, the underlying cause of the yen’s weakness is the long-term decline in Japan’s economic competitiveness. This weakness has, however, been exacerbated by recent monetary policy, particularly the Bank of Japan’s excessively low policy interest rate and its reluctance to adjust it. The real policy interest rate—the policy rate minus the overall inflation rate—stands at 0.88% in the United States but is –2.4% in Japan. It looks as if Japan is actively pursuing yen depreciation.

Japan is a country with extremely low food and energy self-sufficiency, and is therefore dependent on imports to meet the shortfall. Tacitly allowing currency depreciation of this magnitude inevitably causes hardship for many households and domestic-facing businesses. If this pain is continually mitigated through tax cuts, subsidies, or payouts, fiscal conditions will worsen continuously. This will pour fuel into future inflationary fires. Excessively low real interest rates are also causing asset price distortions in certain parts of the economy, such as real estate and the stock market.

Meanwhile, most Japanese companies in the United States are struggling with soaring local staff costs. I often hear lamentations of Japan’s declining national strength along the lines of “If the yen’s weakness persists, we won’t be able to secure good talent,” and “the competitiveness of Japanese companies overseas will significantly weaken over the next decade.”

There are many in Japan, including in the government, who do not want to see interest rates rise. While understandable in the short term, it is crucial to recognize that there will inevitably be future blowback from maintaining unbalanced low interest rates.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Times Square, New York City, September 10, 2025. © Jimin Kim/SOPA Images via Zuma Press Wire/Kyōdō.)

AloJapan.com