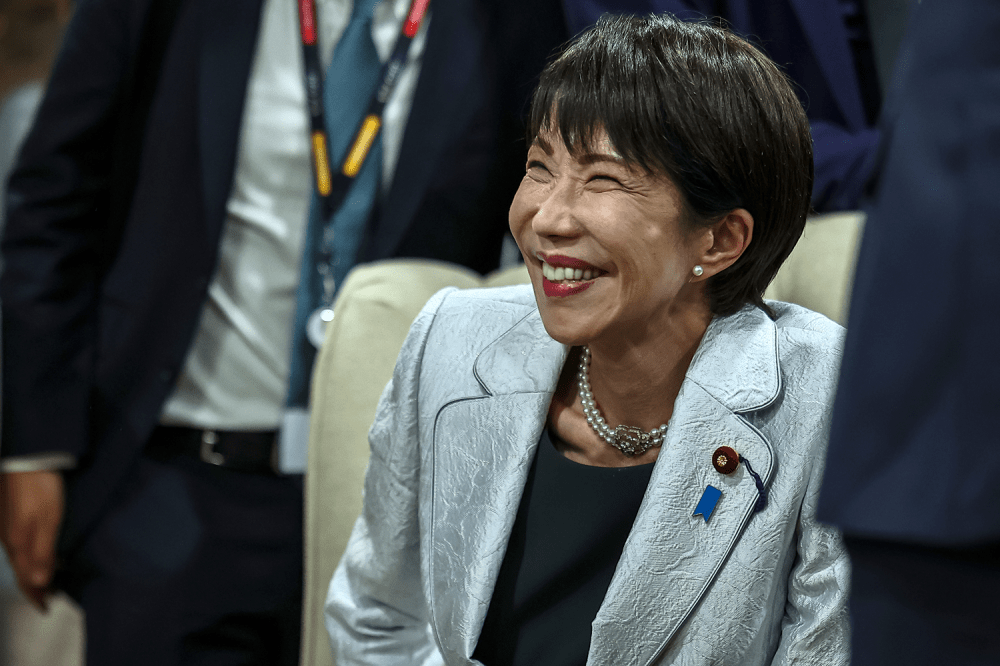

Recently elected Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has proposed an ambitious 21 trillion yen ($135 billion) spending program that puts new stresses on already heavily overdrawn government coffers and raises the specter of a Liz Truss-style market shock. For international investors, it adds further uncertainty, but for the Japanese bond market, it is déjà vu all over again.

The plan fulfills Takaichi’s campaign promise of a “proactive fiscal policy” that is designed to bring Japan out of its long stupor since the collapse of the bubble economy back in 1990. Taking note of public opinion polls, a major part of the spending will be intended to help people cope with higher prices through various subsidies rather than taking more painful steps to control inflation itself.

Recently elected Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has proposed an ambitious 21 trillion yen ($135 billion) spending program that puts new stresses on already heavily overdrawn government coffers and raises the specter of a Liz Truss-style market shock. For international investors, it adds further uncertainty, but for the Japanese bond market, it is déjà vu all over again.

The plan fulfills Takaichi’s campaign promise of a “proactive fiscal policy” that is designed to bring Japan out of its long stupor since the collapse of the bubble economy back in 1990. Taking note of public opinion polls, a major part of the spending will be intended to help people cope with higher prices through various subsidies rather than taking more painful steps to control inflation itself.

While still low by global standards, Japan’s inflation rate of around 3 percent is being felt by consumers, especially since much of the increase comes in higher costs for food, up 6.4 percent in November compared to levels one year ago, including a 40.2 percent increase in the price of the daily staple of rice. Takaichi has proposed measures that include subsidies for electricity and gas bills as well as cash handouts for households with children.

In addition, she wants to make targeted investments in sectors such as semiconductors and shipbuilding, plans that recall the glory days of Japan’s state economy in the 1950s and 1960s, when the powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry played a key role in the economy—and arguably helped to create the postwar “economic miracle.”

While few would argue with the hopes for a fast-growing Japanese economy, there seems to be little reason to think that Takaichi will succeed where all her predecessors have largely failed. Prior attempts at fiscal stimulus, especially ones attempted in the 1990s with a focus on big infrastructure projects, did little for overall economic growth while pushing the debt load consistently higher.

Despite regular lip service to the idea of “fiscal responsibility,” administrations through the past 30 years have found it easier to spend than to save. The government debt load has soared from just 48 percent of Japan’s annual GDP in 1980 to a peak of more than 258 percent in 2020, according to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). By contrast, the much-debated U.S. debt load is at 125 percent of GDP, according to the IMF.

Takaichi has said that her additional spending will not be a problem, since it will create higher growth and therefore higher tax revenues.

“As we build a robust economy and raise our growth rate, we will reduce the government debt-to-GDP ratio, realize fiscal sustainability, and ensure the confidence of the markets,” she confidently predicted when she rolled out the program in late November.

Markets have been skeptical, and analysts have been quick to compare Takaichi’s claims with the debacle that resulted from a similar attempt by British Prime Minister Liz Truss in 2022. Soon after taking office, Truss announced a robust spending package that she claimed would be a cure-all for all that ailed the economy. The market reaction was quick, with a sharp fall in the value of British government bonds and quick market intervention by the Bank of England, followed by Truss being rapidly ejected from office by her own party.

Such talk of a looming Japanese debt crisis is far from new. As the debt burden has steadily marched into ever higher record territory over the past 35 years, there have been regular, well-reasoned forecasts of how a debt burden that is the highest ever recorded by a major economy (Britain came close during the Napoleonic wars and just after World War II) would create a panic in government bonds. The markets are still waiting.

Through this period, Japan also had among the world’s lowest interest rates, making the debt less expensive to service. This dichotomy prompted one of the most memorable comments on Japan, made by a clearly frustrated Willem Buiter, then the chief economist for Citigroup, who mentioned Japan at a New York meeting in 2010, when the debt level had reached 220 percent of GDP. “Japan is the hardest economy in the world to understand,” he said. “If this were physics, then gravity wouldn’t work in Japan.”

There are several practical reasons for the conundrum. One is that while Japan’s government has racked up high debt loads, it has also been no slacker in piling up assets. This means that the net debt burden, taking into account what the government owns, is a much more manageable 134 percent. That is still high, but it’s at least within the realm of other nations, including Italy at 125 percent and the United States at 97 percent. As economist Jesper Koll noted in June, when bond worries were again in the news, Japan has been the world’s largest creditor country for the past 37 years.

Just as importantly, Japan owes the money to itself, with just 12 percent of public debt held by foreigners, as opposed to 33 percent for U.S. Treasurys. This, in effect, means that there is no debt problem, but rather a balance sheet issue. The government could eliminate the debt by simply tapping its famously frugal citizens and cash-laden corporations through higher taxation. That would have its own domestic repercussions, but international markets would be largely insulated.

Another factor is the very nature of capitalism in Japan. While traders have become more aggressive in recent years, and corporate raiders and foreign hedge funds are no longer a novelty, big Japanese corporations largely work with the government, not against it. This means that they take their considerable profits (especially with the weak yen pushing up the value of overseas earnings) and plough them back into Japanese government bonds. This provides a small but consistent profit and means that they are ready for a global downturn, such as the financial crisis of 2008, when Japan’s biggest bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, bailed out U.S. investment bank Morgan Stanley and helped to stop a full meltdown in the markets. It would be unthinkable for these corporate titans to force a crisis in Japan, even if they might profit individually.

This does not mean that Takaichi’s plans are a good idea. Indeed, the same approach has been tried repeatedly by previous governments, which is exactly why Japan has a debt (sorry, balance sheet) problem. One of the highest-profile initiatives was the “Abenomics” program introduced by Takaichi’s late mentor Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister from 2006 to 2007 and 2012 to 2020.

His “three arrows” of fiscal stimulus, massive monetary easing, and structural reform were meant to pull the economy out of its long-term lackluster growth rate of 1 percent to 1.5 percent. When he left office, the growth rate was virtually the same. In fairness, that is not a bad outcome for an aging society with a shrinking population, especially when there is zero inflation.

Economists also question the unconventional idea of trying to tackle inflation by increasing spending.

“Aggressive fiscal policy increases fiscal risks, which in turn contribute to a weakening of the yen through a decline in currency confidence. This could lead to higher prices and offset the effectiveness of the inflation countermeasures that are the pillar of the economic stimulus package,” said Takahide Kiuchi, the executive economist at the Nomura Research Institute, in an interview.

Another key player in the drama is the Bank of Japan, which is widely expected to push up the short-term policy interest rate by a quarter of a point to a still-modest level of 0.75 percent when it meets from Dec. 18 to Dec. 19. Takaichi had said a year ago that higher rates would be “stupid,” but Japanese media outlets report that she is now on board with the idea in order to stop a weaker Japanese yen from further worsening the inflation outlook.

While a bond market sell-off is highly unlikely for now, economic fundamentals will eventually rule in Japan as they do elsewhere, requiring the government to plug the expanding gap of fresh debt. One basic tenet is that inflation rewards borrowers over creditors. While Japan’s total individual savings of $14 trillion will take a hit in a higher-inflation environment, the government will emerge as the winner. It remains to be seen whether it uses the chance to finally make a meaningful downpayment on its years of largesse or takes the cash to again pay off the voters.

Despite the concern over higher prices, inflation might not be political suicide for Takaichi. The big savers in Japan are the retired baby boomers who managed to stash away money in the high-growth years preceding 1990.

Members of the new generation, who have seen low growth and stagnant (or negative) real wages through their careers, are unlikely to shed a tear for the declining real value of the older generation’s store of wealth. While younger voters have historically been less likely to vote, their numbers are rising and becoming an increasingly important political voice. For now, at least, they seem to like Takaichi’s brand of populism.

AloJapan.com