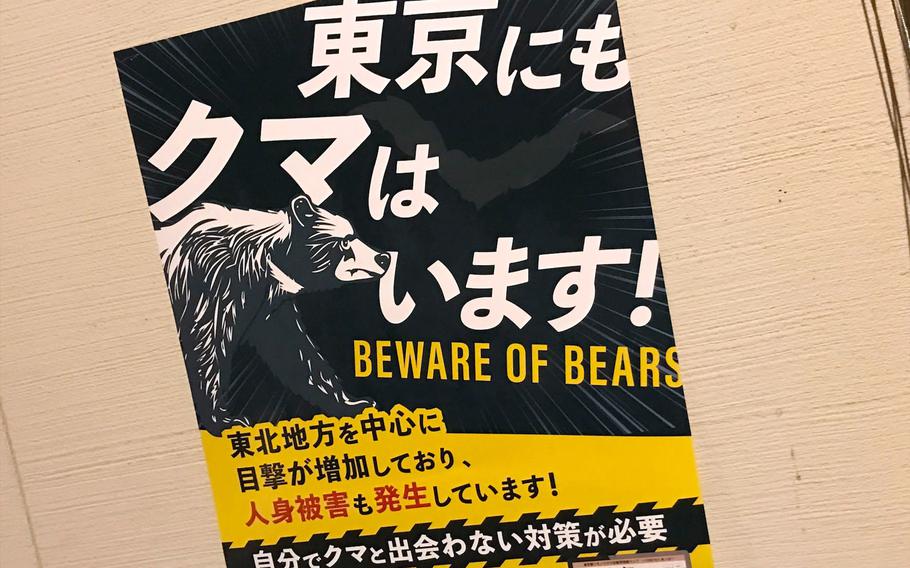

A poster in Tokyo warns residents that the metropolitan area is also home to bears, and that sightings have increased dramatically across the country. (Seth Robson/Stars and Stripes)

The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force was deployed last month to confront an unusual threat in northern Japan: Bears.

The rare mobilization followed a surge in bear encounters nationwide that has left 13 people dead and more than 200 injured across 22 prefectures this year, according to Japan’s Ministry of Environment.

Akita prefecture, in the country’s north, was hit hardest, recording at least 66 attacks and four deaths.

“One of the particular characteristics of this year is that these incidences, these injuries, are happening in urban areas and residential areas,” Akita Gov. Kenta Suzuki told reporters Thursday at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in Tokyo.

Suzuki said that while the number of deaths remains small compared with causes such as traffic accidents, the attacks have generated “very high levels of fear among the population” and caused significant economic disruption in his largely rural prefecture.

“As a result of this situation, on Oct. 28 of this year, we made an emergency request to the Ministry of Defense in order to have the Self-Defense Forces involved in supporting this situation,” he said.

About 900 Japanese soldiers were deployed to Akita between Nov. 5 and Nov. 25. Their role was limited to logistical support, including transporting traps and removing bears that had already been killed by hunters and other local teams, Suzuki said.

Suzuki acknowledged that the Self-Defense Forces are primarily tasked with national defense but said the scale of the crisis left local authorities with few alternatives.

“I believe that it was exactly because local resources were not sufficient to deal with the situation that we had to make this request for emergency measures to the Ministry of Defense,” he said.

Experts attribute the spike in bear encounters to several overlapping factors, including expanding forests, shrinking food supplies, declining rural populations and a drop in the number of hunters.

Japan once relied heavily on wood for fuel and regularly hunted wildlife, but forests have expanded in recent decades as those practices declined, said Mayumi Yokoyama, a professor at the University of Hyogo.

Because bears were once considered close to extinction, conservation efforts also reduced hunting pressure, Yokoyama said Friday during a livestreamed news conference hosted by Foreign Press Center Japan.

Abandoned farmland has further drawn bears closer to towns and cities, increasing the likelihood of encounters with humans, she said.

AloJapan.com