In 1938, the literary scholar Yamagishi Tokuhei was browsing the Travel section of the Imperial Household Library in Tokyo when he stumbled across an unfamiliar manuscript. He discovered that it was an early 18th-century copy of a long-forgotten medieval text called Towazugatari. This autobiographical work (usually known in English as A Tale Unasked and newly translated for Penguin Classics by Meredith McKinney) tells the story of Lady Nijō, a high-status member of the court of the retired Emperor Go-Fukakusa (1243-1304).

Nijō, who was born in Kyoto in 1258, came from a leading aristocratic family: many of her male relatives, including her father, served the emperor as senior counsellors, and her mother was also a prominent courtier. But the future memoirist had a difficult start in life: her mother died when she was two, and so, from the age of four, she was raised at Go-Fukakusa’s court. By 14, she was his concubine, a position she managed to retain for more than a decade, despite the hostility of his primary consort and constant competition with other women.

Then, in 1283, Nijō was suddenly expelled from court – possibly because of her clandestine affair with Go-Fukakusa’s half-brother (and bitter rival) Kameyama. On his deathbed, her father had warned her that, in such a situation, she would have two choices: to become a Buddhist nun or to ‘make yourself a name among the brothels’. When the crisis came, Nijō chose the former option, but she recognised that she was unsuited to life in the cloistered communities to which many high-status women retreated. Consequently, the second half of her memoir describes the many pilgrimages she undertook in her thirties and forties, travelling to far-flung temples and shrines across Japan.

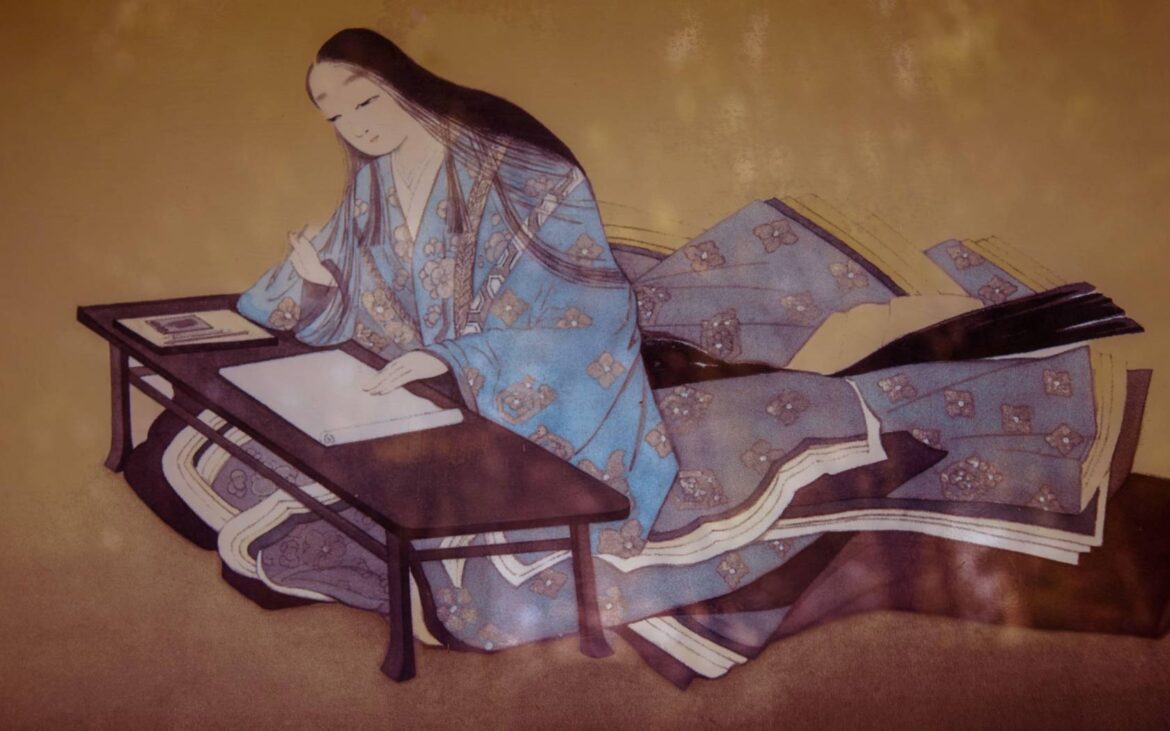

A Tale Unasked, written when Nijō was in her late forties, is a remarkable account of a remarkable life, offering unusual insights into the thoughts and experiences of a medieval woman. Even more astounding is that it is just one of several autobiographical works produced by Japanese noblewomen during the Heian (794-1185) and Kamakura (1185-1333) periods.

By far the best known is Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book, which combines lively descriptions of late 11th-century court life with lists which reveal her strongly held opinions. Some of these are extremely relatable (‘Everything that cries in the night is wonderful. With the exception, of course, of babies’), but others are very much of their time. Her list of vulgar things includes ‘Snow falling on the houses of the common people’, and she considered ‘Adopting a child who turns out to be ugly’ to be a deeply regrettable thing.

Several other diaries (as they are conventionally labelled, though most are closer in form to what we would now call memoir) focus on female sorrows, for the genre was shaped by both the Buddhist belief that ‘Life is suffering’, and a contemporary preoccupation with the impermanence of this world. Lady Murasaki (c. 973-c. 1020), best known as the author of The Tale of Genji, produced a memoir of her time as a lady-in-waiting at the court of Empress Shōshi, in which she wrote of ‘tasting the bitterness of life to the very full’. In The Kagerō Diary, a woman known to posterity only as Michitsuna’s Mother describes her unhappy marriage, while As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams records the spiritual life and many pilgrimages of the melancholy Lady Sarashina.

Reading these deeply personal narratives as a specialist in the European Middle Ages, I find it hard not to feel envious. There are important medieval writings by European women – ranging from Dhuoda’s Liber Manualis (a conduct book written by a Carolingian mother for her adolescent son) to the Lais of Marie de France, and from Abbess Hildegard of Bingen’s medical treatises to Christine de Pizan’s proto-feminist The City of Ladies. And the lives of holy women are often well documented, mostly by male hagiographers, but occasionally in their own words. In the century after Lady Nijō committed her life to paper, female mystics such as Bridget of Sweden and Julian of Norwich began to write down (or dictate) their visions, producing spiritual autobiographies that offer valuable insights into the piety of late medieval women.

But the first European text that seems truly comparable to A Tale Unasked is The Book of Margery Kempe – and not just because it, too, was rediscovered by chance in the 1930s. Kempe (c. 1373-c. 1440), a merchant’s wife from King’s Lynn, lived a more conventional existence than Lady Nijō: she married at 20, gave birth to 14 children, and ran her own brewing business, until it went bankrupt. Her life was defined by her deeply held Christian faith, which intensified after the birth of her first child triggered a bout of depression (from which she emerged only after Jesus personally reassured her of His love), and which was rather more intense than Nijō’s somewhat pragmatic Buddhist vocation.

And yet, there are striking similarities between their lives. Like Margery, Nijō found motherhood traumatic: three of her four children were swiftly removed from her care, and though she was able to nurse her final son (noting that she experienced ‘a strong surge of motherly love and suddenly understood what my mother would have felt for me’), she later wrote that ‘I essentially had no child to pass anything on to.’ Both were also given to frequent weeping – though Nijō’s decorously tear-soaked sleeves pale in comparison to Margery’s hysterical wailing, which drove one frazzled priest to remind her that ‘Woman, Jesus is long since dead.’

Above all, their stories highlight the vulnerability of women – even wealthy, well-connected and clever women – in a world dominated by the opposite sex. In medieval Japan, it was customary for powerful men to have not just a primary wife but numerous concubines, and Nijō’s memoir opens with an account, quite horrifying to modern sensibilities, of how, in her early teens, she awoke to find Go-Fukakusa in bed with her. The next night, having justified his actions by claiming that he had loved her since she was a child, he returned and raped her. For the rest of her time at court, she was forced to submit to his every whim, even acting as his pimp, and though she clearly loved him in her own way, the power imbalance is clear.

In comparison, Margery was relatively fortunate: her long-suffering husband, John Kempe, though he expected her to pay his many debts and only very reluctantly agreed to a chaste marriage, is certainly not the villain of her story. She was also much more outspoken than Nijō, and faced the consequences of displeasing powerful men. On more than one occasion, she was accused of heresy, avoiding the death penalty only because ‘God gave her the grace to answer well’ when she was interrogated by great churchmen.

Yet, despite such difficulties, neither of these women was without agency, and both were deeply engaged with the world around them – their recollections are much more than memoirs of men and motherhood. Alongside her many domestic responsibilities, Margery ran several businesses; after the brewery failed, she ‘got herself two good horses and a man to grind people’s corn’ and set up a mill. And Nijō, despite her practical and emotional dependency on Go-Fukakusa, took several other lovers during her years at court, and was a sharp observer of dynastic politics.

Both women were also greatly empowered by their faith, which provided emotional consolation and a sense of purpose, as well as a justification for extensive travel – something which was rarely possible for medieval women since, as Go-Fukakusa mused when he found out about Nijō’s new life: ‘It’s quite acceptable for a man to travel hither and yon… [but] all sorts of things stand in a woman’s way to hinder her in this kind of wandering practice.’ He, like many medieval men, also felt justified in questioning the virtue of female travellers, accusing his former lover of sleeping with her fellow pilgrims.

Despite social constraints and hostile attitudes, both women travelled widely: Nijō spent nearly two decades on pilgrimage, while Margery visited Aachen, Rome, and the Holy Land, as well as numerous English shrines. Being a female traveller was not without its challenges, and both women recall frequent struggles with predatory men and uncongenial companions, as well as practical problems, such as lice-infested lodgings. But their restless souls clearly derived great satisfaction from their religious wanderings – for, as Nijō explained, ‘I didn’t have it in me to quietly devote myself to religious study.’

At the end of A Tale Unasked, Nijō dismissed her memoir as ‘this foolish tale of mine’, claiming that ‘I have no hope that it will remain for future generations to remember me by.’ Perhaps this was false modesty (for, like all memoirists, Nijō was heavily influenced by the literary conventions of her time), or perhaps she really did believe that her book would be lost to the vagaries of time. Either way, we should be grateful that she was proved wrong and that her words still offer us a portal into her world. Because this powerful story, powerfully told, deserves to be heard.

AloJapan.com