(Photo by Shoji Kudaka/Stripes Okinawa)

Just south of Naha in Tomigusuku City, a park with lush forest trails, monuments, a massive playground and a superb view of the southwest coast, is also the site of World War II history.

Kaigungo Koen, which means “Navy tunnel complex park,” is the site of the Former Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters. Every year, 100,000 people visit the site in Okinawa to learn more about the history of the headquarters, the people who fought inside it and the tragedies that unfolded during the war.

From its surface, the hilly Kaigungo Koen has the look of a neat public park, but over 80 years ago, this site carried strategical importance during the Battle of Okinawa.

History

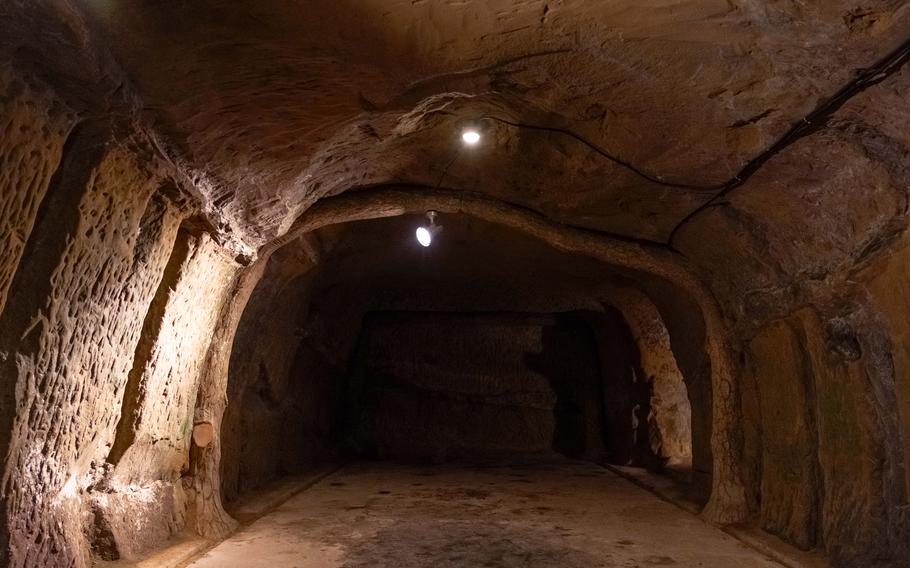

In August 1944, the tunnel complex’s construction quickly began and was completed in about four months. Since the tunnel was designated top secret, no civilians were mobilized in the construction.

The tunnel complex containing a series of passageways, measures 450 meters in length and was manually dug using pickaxes and hoes. Visitors can still see the axe marks in some of the walls of the bunker today.

According to the museum’s website, construction continued for four months to accommodate the growing number of Navy personnel and to prepare a stronghold for the Oroku Japanese Naval Base forces.

(Photo by Shoji Kudaka/Stripes Okinawa)

(Photo by Shoji Kudaka/Stripes Okinawa)

During the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429 – 1879), the site served as an outpost and lookout for smoke signals announcing the arrival of foreign ships. The hill would once again be used as a lookout during World War II, but this time in defense of the nearby Oroku Kaigun Hikojo (Oroku Air Base/Navy Oroku Airfield), now known as Naha Airport. During the war, the hill was called “74 kochi (highland),” a reference to its height.

According to the park website, about 10,000 members of the Imperial Japanese Navy were stationed in Okinawa and of those, 4,000 were assigned to the underground bunker.

As the battle between the U.S. and Japanese forces intensified, the Navy would compromise its headquarters to provide some of its personnel to support the 32nd Army in Shuri.

The Last Days

According to a brochure of the park, following an order from the 32nd Army’s commander, Lieutenant General Ushijima, the Oroku Japanese Naval Forces retreated on May 22, 1945, to the south only to quickly move back into the bunker as it ended up being a better stronghold than the new position.

According to Rear Admiral Ota’s biography “Okinawa kenmin kaku tatakaeri” by non-fiction writer Yozo Tamura, however, the return was not voluntary.

The book says the decision was based upon an agreement made in May 1944 between the Imperial Army and Navy that put the Imperial Navy in Okinawa under the command of General Ushijima of the 32nd Army in the case of ground operations, which forced the Imperial Navy to head back to the tunnel complex.

(Photo by Shoji Kudaka/Stripes Okinawa)

(Photo by Shoji Kudaka/Stripes Okinawa)

Up to this point, the Imperial Navy had provided to the 32nd Army more than 2,000 personnel, who happened to be their best ones. Before attempting to relocate to the south, the naval forces destroyed weapons that could not be carried, thus drastically reducing their resources when they had to return to the bunker.

On June 4, 1945, the U.S. 6th Marine Division landed near Oroku Peninsula and close to the Navy Underground headquarters. On June 6, the U.S. Marines conquered the Oroku Peninsula, narrowing the battlefield to a 4-km radius of the underground headquarters.

Recognizing the forthcoming fall of the headquarters, Rear Admiral Ota sent out one last telegram for which the line “Okinawa kenmin kaku tatakaeri (This is how the people of Okinawa have fought the war)” is known for. Ota’s message to the navy vice admiral was a reminder to officials to remember the sacrifice local Okinawans paid in the war.

On June 10, the Marines began directly assaulting the underground headquarters, which were filled with injured personnel.

On the afternoon of June 12, the top of the high ground was conquered by the Marines. Remaining personnel were ordered to leave the bunker and just past midnight on June 13, Rear Admiral Ota and his six officers killed themselves.

To the Bunker

The entrance to the bunker inside the Visitors’ Center has illustrations and panels displaying information about the Battle of Okinawa to provide more context of the bunker’s history.

At the entrance, there is an exhibit of items like pens, tags, water canteens and more that were excavated from the bunker after the war.

To access the underground headquarters, visitors walk 105 steps down to the tunnels. According to the park’s website, the tunnels run 450 meters in total, but only 300 meters are open to the public. The park’s brochure indicates that the main tunnel runs as if drawing a triangle. Once you reach the end of the stairs, you find yourself at one corner of the triangle. The first room you encounter is the Signal Room, where visitors can touch a code transmitter.

(Photo by Shoji Kudaka/Stripes Okinawa)

Given that many telegrams were sent from there during the war, including Rear Admiral Ota’s farewell message, this room has historical importance.

By following the arrows, visitors will be guided to the Operation Room, Staff Room, Code Room, Medical Room and three Generator Rooms. Access to some of them requires going through smaller tunnels branching out of the main one, which makes it seem like a maze. In the Staff Room, the walls are riddled with holes from the grenades Ota and his officers used to end their lives.

After turning the west corner, visitors will see rooms lined up. During the last days of the headquarters, sailors were crammed there to the point where they slept standing up, according to the exhibit on the top floor. As the battle intensified, they could not leave the tunnels, creating an extremely difficult and hectic environment with wounded troops, piling bodies and bodily fluids.

The last feature of the tunnel is the Commanding Officer’s Room, which can be found along the third side, before the route heads back to the Signal Room. Admiral Ota left a farewell poem on the wall, which means “Born as a man, nothing fulfills me more than to die under the banner of the Emperor.”

The well-maintained and clean appearance of the underground tunnels today, may make it difficult to understand just how cramped and grueling the close quarters must have been on the young men squeezed in there. And while its forested exterior is an inviting place to get a breath of fresh air and some steps in, it also offers a glimpse into the area’s gruesome history.

The Former Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters

GPS Coordinates: 26.186457, 127.676925

Hours: 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. (last admission at 4:30 p.m.)

Admission: 600 yen (approx. $3.87) for high school students and above, 300 yen for middle school and elementary school students.

Website

Dontei Tomigusuku

The best way to describe this local fast-food chain would be “Okinawan Yoshinoya.” Just a few minutes’ drive from Kaigungo Koen, Dontei Tomigusuku is a good option for those who want an affordable and quick meal. Their menu features gyudon (490 yen), cutlet curry (700 yen), Okinawa soba noodles (750 yen) and more. I tried gyudon, which I found pretty satisfying for its price. Dining at this place lets you experience what a regular Okinawa would eat for lunch or dinner when they need something quick and easy.

Kateera mui (Kobobukiyama)

The Imperial Navy built another tunnel complex at this location around the same time as underground headquarters in Tomigusuku City. Measuring 350 meters in length, the tunnels accommodated rooms for a commanding officer, sailors, code and more. With its entrance shield by a fence, the inner portions cannot be accessed. The location is now known as Tabaru Koen (park).

AloJapan.com