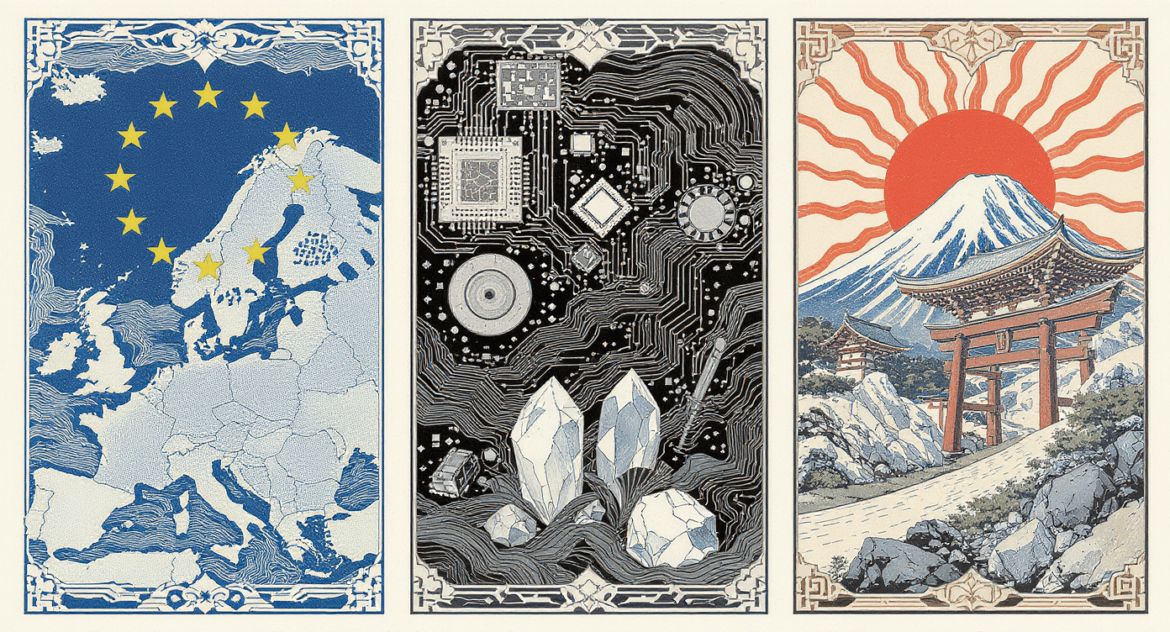

As Europe races to bullet-proof its supply of the obscure minerals that keep its economy running and its jets in the air, it’s turning to an unlikely coach: resource-poor, crisis-hardened Japan.

Commission Vice-President Stéphane Séjourné is set to unveil the EU’s long-awaited plan to make Europe’s supply chains for critical raw materials more resilient on 3 December. The initiative – dubbed ‘Resource EU’ – is repeatedly described by Brussels as ‘Japan-inspired’.

That inspiration comes as Europe finds itself squeezed in an era of escalating trade skirmishes. To the west, Donald Trump’s America is slapping tariffs on friend and foe alike. To the east, China has broadened its use of export controls, tightening its grip on rare earths – the obscure yet indispensable materials embedded in everything from smartphones to the fighter jets patrolling Europe’s borders.

Brussels, eager not to be caught flat-footed, has been scrambling to build its own resilience. In 2023, the EU drafted its “Economic Security Strategy.” A year later, it passed the “Critical Raw Materials Act”.

Next week, the Commission is expected to table a sweeping Economic Security Package, combining a “doctrine” aimed at deterring future trade coercion with the Resource EU plan to secure Europe’s access to rare earths and related minerals.

The first hint came in late October, when President Ursula von der Leyen announced a European scheme for joint purchasing and stockpiling – a day after Euractiv revealed that Commission officials had visited Japan more often than any other non-EU country this year. The clear subtext was that Tokyo’s long experience in securing critical materials had become Brussels’ north star.

Séjourné soon leaned into that narrative. On social media, he said Resource EU would include a centre for common purchasing and stockpiling, sur le modèle japonais. A week before the official announcement, he told the European Parliament the Commission would create a “European Centre for Critical Raw Materials” to act as an EU-wide supply hub.

Japan’s head start

Few countries are as exposed to supply-chain shocks as resource-poor Japan, whose manufacturing muscle depends on a steady inflow of imported minerals. Tokyo began preparing for coercion long before Europe did. When China briefly choked rare-earth shipments to Japan in 2010, the government resolved to reduce its dependency on Beijing’s near-monopoly.

Central to that effort is JOGMEC – the Japan Organisation for Metals and Energy Security – an independent agency that Séjourné visited in September and Trade Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič toured in May. Its roughly 600 employees have helped cut Japan’s reliance on China for rare earths from 90 per cent to 60 – 70%. By comparison, the EU still sources 100% of the rare earths used in permanent magnets, and 97% of its magnesium, from China.

JOGMEC’s strategy is simple: spend money, deploy expertise, and broaden supply. It finances domestic processing, supports Japanese firms abroad, and helps crack open new sources of raw materials worldwide.

In Australia, JOGMEC invested this summer in a fluorite exploration project – fluorite being vital for refrigerants and semiconductor production.

In September, it met with African partners such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and Namibia, where it has several rare-earth projects.

The Commission’s 2025 competitiveness report notes Japanese partnerships in Peru, New Zealand, Malaysia, the UAE, Brazil, and Norway.

Tokyo is now preparing to raise the ceiling on government support for such projects from 50 per cent to 75 per cent. Its Ministry of Economy, Trade, & Industry (METI) also offers subsidies and tax breaks to encourage firms to diversify their sourcing. The money spigot is open even to foreign companies, provided they strengthen Japan’s industrial base.

Japan’s secret stockpiles

Another pillar of Japan’s strategy is stockpiling – and here JOGMEC plays a quasi-mystical role. The agency directly procures critical materials and stores them in an undisclosed location – or locations – treated as state secrets. Taxpayers finance the stockpiles, but their value also makes them financial assets for the state.

The rules are strict. Companies must first exhaust their own inventories before JOGMEC releases reserves. The agency may intervene when prices hit pre-determined crisis levels, and METI’s minister can order sales from the emergency hoard. Confidentiality is absolute: leaking JOGMEC information is punishable by up to a year of imprisonment with hard labour or a fine.

In the Commission’s own words, secrecy makes economic coercion “more difficult.”

This degree of opacity raises immediate questions for Brussels – which generally prefers transparency and shared governance –as it sketches its own version of a stockpiling regime.

‘Made with Common Values’

Creating a truly JOGMEC-like institution would mark a significant shift in power from EU capitals to the Commission. Yet parts of the architecture already exist. The Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship, and SMEs (DG GROW) signed a cooperation agreement with JOGMEC in 2023, and the Critical Raw Materials Act requires EU countries to report national stockpiles and enables joint purchasing.

Still, Europe lacks key ingredients. If the new European Centre is to run its own secure warehouses, a French minister may need to trust that the rare earths destined for future Rafale jets are sitting safely inside a Romanian mountain bunker. And Europe has no spare army of geologists waiting to scour Africa or South America for new deposits.

Then there is the money. Under current budget constraints, officials suggest that Resource EU may rely on old programmes repackaged under new labels – a technique the Commission is increasingly using. One candidate, the European Defence Industry Programme, totals just €1.5 billion, and hopes for significant top-ups via third-country contributions to the SAFE defence-loans scheme have not materialised.

A final complication is political. Europe’s current mantra –‘European sovereignty’ and ‘Made in Europe’ – sits uneasily with the reality that securing its supply chains inevitably requires sourcing abroad. Japanese business warns that heavy-handed industrial policy can hit friends as hard as adversaries. Their preferred slogan is ‘Made with Common Values’.

A DG TRADE official said this week that the EU’s upcoming Economic Security Doctrine will put strong emphasis on partnerships. Those comments reflect Séjourné’s own assurances in Tokyo that the EU wants to strengthen cooperation, not jeopardise it.

The full Economic Security Package – the doctrine plus the Resource EU plan – is set to be presented on 3 December.

Brussels insists the plan won’t unsettle its allies. Perhaps. But in a world where minerals are becoming bargaining chips, Europe is learning what Japan learned long ago – if you don’t control the raw materials, someone else will control you.

(mhk, cm)

AloJapan.com