At 5 AM, Dvir Ben-Ami is already awake. Like every uchi-deshi, a student who lives inside the dojo, he starts the day by cleaning the dojo, the Japanese training hall, and the adjacent shrine. Windows are opened, the hall aired out, dust wiped away, and the grounds raked. At exactly 6 AM, morning practice begins and, as in the old days, there is no talking, only demonstrations, precise movements and listening to the body.

So, in the middle of the village of Iwama, where the founder of aikido taught until his death, Ben-Ami is fulfilling a 30-year dream and spending two weeks living as the first disciples of O Sensei once did.

21 View gallery

Aikido is a Japanese martial art that combines empty-hand fighting with work using swords, staffs and knives. Its founder, Morihei Ueshiba, known as O Sensei, created the method based on lethal combat techniques of the ancient samurai. Ben-Ami, 58, a veteran aikido teacher from Herzliya with 50 years of experience in Japanese martial arts, has finally realized an old dream, traveling to Japan to train in a small, picturesque village alongside some of the world’s best teachers, just like in the movies. In a conversation with ynet, he describes the electrifying experience he went through at the ancient temple of the martial art.

“Going to Japan has been a distant dream for 30 years. When I was competing in judo in high school there was a trip planned to Japan that was eventually canceled. After the army I found my way to aikido and traveled in the East, and all the time I had Japan in my head. In the end I gave up and came back to get a degree at the university.”

21 View gallery

Iwama’s dojo training complex, seen from outside

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

And this is how it looks inside

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

Ben-Ami laughs. “The kids grew up, the budget was freed up, and a student of mine who decided to go to Japan to fulfill a dream suggested I join him.”

On a Friday evening he landed in Tokyo with two longtime students, and by Sunday morning they were already sweating on the mat at the mythic training center, the Hombu Dojo. “We thought it would be a huge hall, but it was a modest building with pictures of the founder everywhere,” he says.

21 View gallery

Morning class at the dojo

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

The dojo during an evening class

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

He adds, “In Sunday morning class there were dozens of trainees and there was silence. Everything is ceremonial and quiet. Unlike training in Israel, there is almost no talking. The teacher demonstrates and the students understand through their eyes and bodies.”

At the end of the intense practice, they took a train an hour away to the pastoral village of Iwama, where the founder withdrew after World War II and established a unique school in a traditional Zen atmosphere, teaching there until his death in 1969. “The moment you leave the station there is a statue of O Sensei,” Ben-Ami says. “Along the main road there are stones with his pictures, and you realize his presence in the town is very strong.”

Ben-Ami discovered that O Sensei was not only a fighter but also a religious man tied to the Shinto tradition. “It is a completely religious place and you do not train there,” he says. “The courtyard is paved with small stones, the gravel is arranged in straight lines, and a statue of O Sensei looks over everything. Inside there are ritual items and a holy ark.”

21 View gallery

‘The kids grew up, so I fulfilled the dream’ Ben-Ami in an evening class

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

Here the tourist part ends and the training begins. “You’re not a guest or a tourist, but a resident student, exactly like in those days,” Ben-Ami says. “You get up at 5 in the morning. Until 5:45 you clean the dojo and the shrine. You open windows, air out the hall, clean dust and rake the grounds. At 6 a.m. morning practice starts.”

“After the warm-up there are conditioning drills. You attack each other very, very hard. Really hard. To strengthen the hands and the blocks. It’s a physical experience that’s hard to explain to someone who hasn’t tried it.”

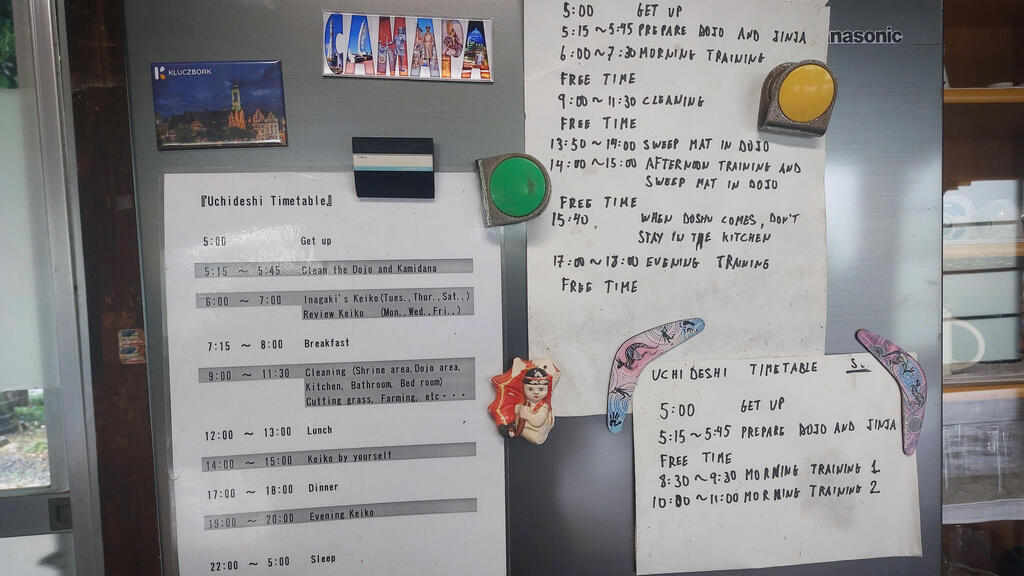

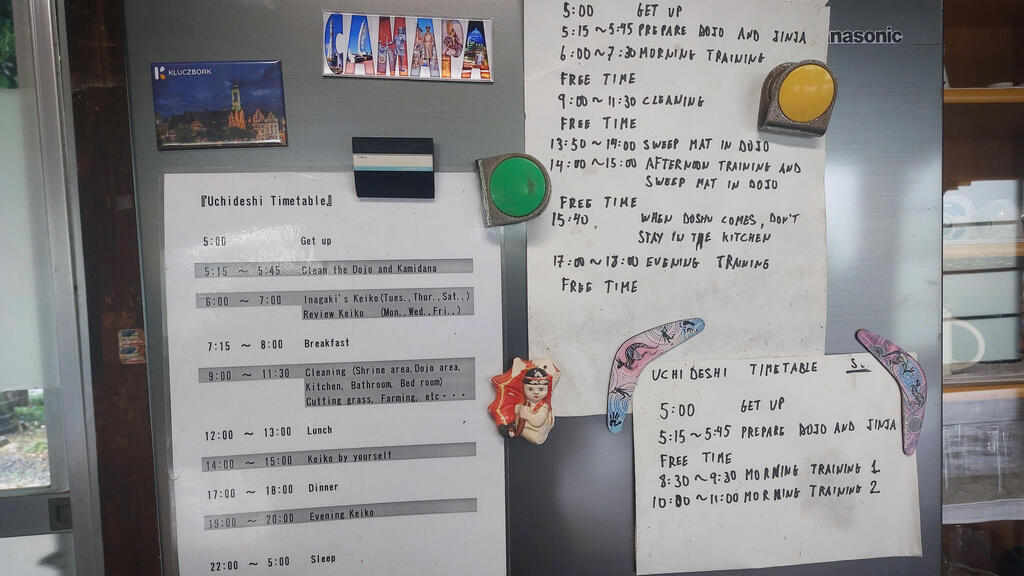

21 View gallery

Training schedules

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

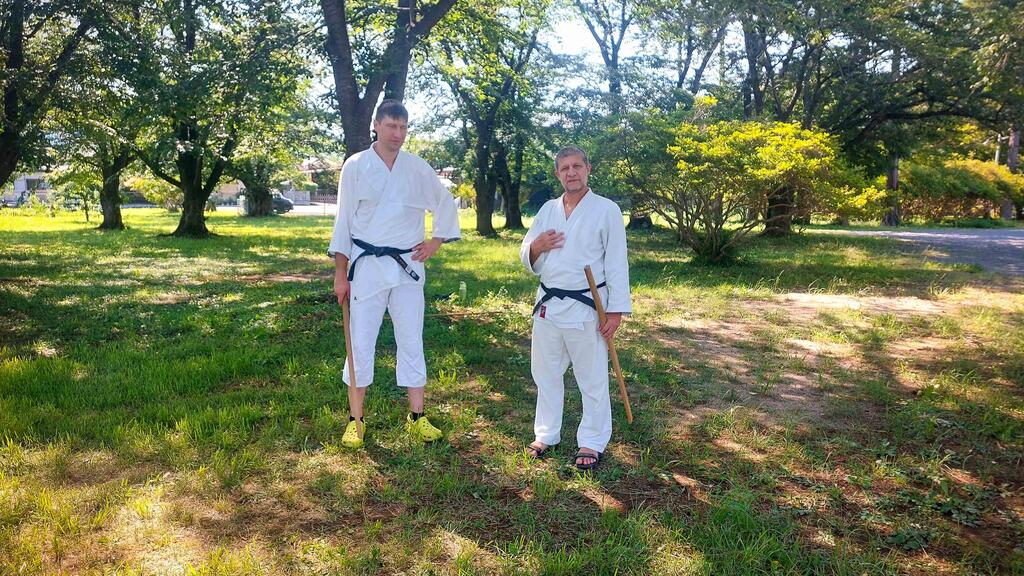

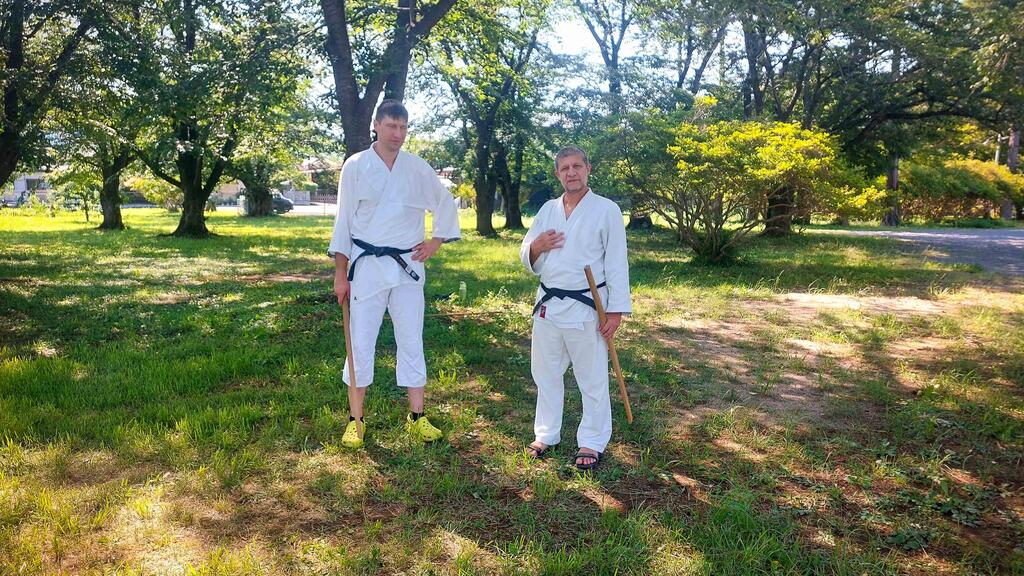

Weeding outside the dojo, like military-style chores

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

Then they move to traditional weapons practice. “There is work with a sword or a staff. We train outside on the grounds. This is the daily weapons class. After that there is a short time for breakfast and then we go to maintenance work on the farm.”

“At 9 a.m. the chores begin. Pulling weeds, cleaning the shrine, mowing grass, cleaning the dojo, while your body still hurts from the morning practice. We work until 11:30. Then lunch, which we cook for ourselves. At 2 p.m. there is an empty-hand class. We go over what we did in the morning but more calmly. This is an important class because here you put in the connecting links between the fast demonstrations of the morning and deeper understanding.”

21 View gallery

Afternoon session, this time independent sword practice

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

העיירה איוואמה

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

“The dojo isn’t big and sometimes it’s crowded. We work empty-hand. There is a bit more talking than at the Hombu Dojo in Tokyo, and there is an interesting method for switching partners,” he says. “The veterans stay in place, the less experienced move among everyone. After each technique you bow and move on to the next trainee.”

When class ends, they return to cleaning. “There are brooms and damp towels. We clean the mat and the walls. It’s basically an inspection, and regardless of rank or experience everyone takes part. In Israel this would take an hour, in Japan it takes a few minutes.”

After cleanup some trainees stay for open practice. “A lot of learning happens then. Practitioners ask questions and work with whoever they want. Learning isn’t only in class, it continues 24 hours a day.”

21 View gallery

Conditioning drills during morning practice

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

Training uniforms airing out

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

At the end of the day they eat dinner in the modest kitchen and get ready to sleep on mats inside the dojo. “We slept together on mats we trained on. They’re made of compressed straw and they are brutally hard, not like in Israel. At first it’s hard to fall asleep, jet lag, overload of experiences, your head is full. But after a few days you fall asleep instantly and get up again at 5 a.m. for a new training day.”

After a few days, the injuries arrive. “Suddenly I see my feet are swollen and I can’t see my ankles. They put cabbage leaves on me, traditional medicine to reduce swelling, and I lay with my legs up. It happens sometimes. The body just breaks down and is rebuilt.”

21 View gallery

During morning chores, there’s room to have some fun, too

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

There was a diverse community there. “There were seven people from Bulgaria who knew English and were sharp, and we connected very quickly. There were also people from Russia who didn’t know English, so it was harder.”

“Very friendly. They want to help and they are happy someone comes. Training in Iwama is much more intimate than the world center, the Hombu Dojo in Tokyo, and they have an important custom. Everyone brings small gifts for the guests. We brought photos and hamsas, and they gave us all kinds of gifts back.”

21 View gallery

Between classes, there’s time to explore, too

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

Thorough pre-event cleaning of the shrine ahead of a prayer ceremony

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

What were the costs of the training camp?

“Lodging and stay fees cost us 25 shekels a day. Iwama is not a business, it’s a mission. We were lucky to take part in two rare events, an intensive seminar with many people from Tokyo and a visit by the Doshu, O Sensei’s grandson. There was a religious ceremony and a shared meal. A truly special experience.”

“Israelis who admire modern Japanese culture, outgoing bloggers and colorful foods might find it hard to understand why you would spend a vacation in a small, sleepy village. But for martial arts students it is an emotional and mental connection that can’t be put into words. You can’t come without coordination in advance. You need a background in aikido and a recommendation letter from your personal teacher.”

21 View gallery

Between classes: treatment for sore feet

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

reparing offerings for the gods; Later they are taken to the shrine

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

Eating between classes

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

And what happens to the soul after fulfilling a dream of 30 years?

“I imagined it would be even harder in terms of intensity and injuries, but it went fine. The training organized a lot of emphases for me and gave me material to think about that really affects me as a student and as a teacher. I fulfilled a dream, but the dream continues. It’s not like climbing Everest and finishing. It’s a path, and there are already talks about the next trip.”

21 View gallery

Workshop participants outside the aikido shrine

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

Evening class with senior instructor Inagaki Sensei

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

21 View gallery

Farewell photo with senior instructor Inagaki Sensei

(Photo: Dvir Ben-Ami)

AloJapan.com