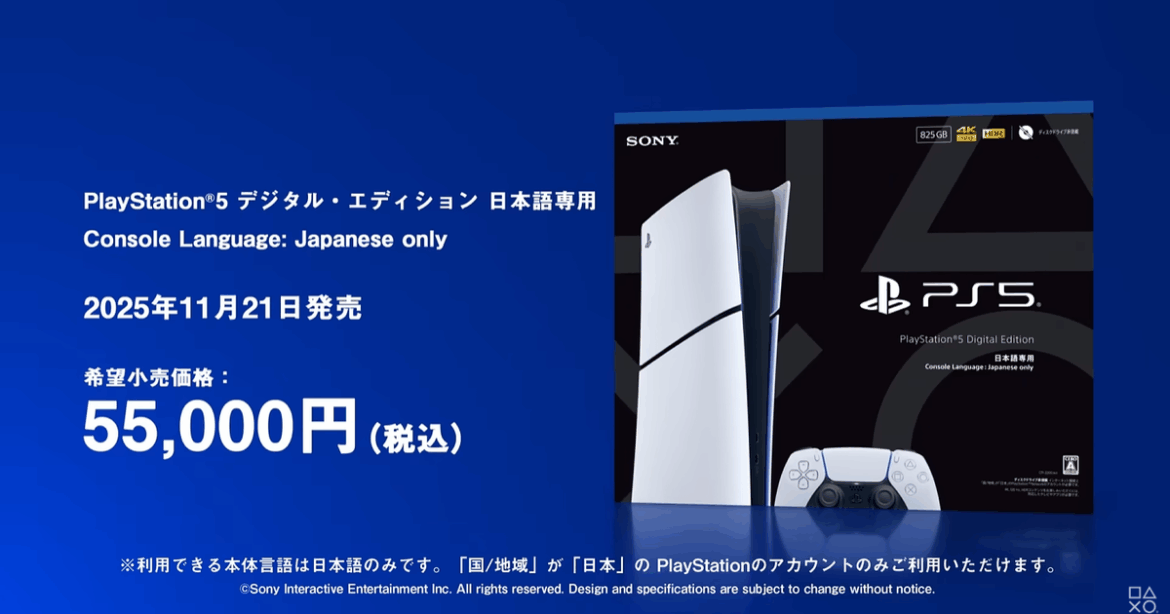

Earlier this month, Sony followed Nintendo’s lead by launching a Japan-only version of the PS5 that’s priced at a significant discount to the console’s SRP everywhere else in the world. The first sales data to come in since the launch suggests that the gambit has, unsurprisingly, been quite popular; sales of the PS5 quadrupled in Japan (from an admittedly low starting point) in the first week of the new version being on sale, though the real impact is most likely to be felt in boosted hardware sales around major software launches.

While consumers may reasonably fret that this signals a turn back towards the bad old days of region-locked consoles, the reasoning behind Sony and Nintendo’s creation of Japan-only hardware editions – locked to Japan’s digital store and with language options disabled in the operating system – is straightforward.

The collapse in value of the Japanese Yen has made international pricing for things like consumer technology products extremely high for consumers. Meanwhile, concerns over affordability even for domestic goods and largely stagnant wages in many sectors have made consumers more price-sensitive than ever – a killer combination for discretionary purchase items like PlayStation or Switch.

There’s a degree of home nation pride involved in Japanese companies not wanting to price themselves out of the market in their own country, of course. For Nintendo, however, some kind of strategy to address affordability in Japan was unavoidable – Japan remains an incredibly large and important market for its products, whereas Sony’s sales in Japan peaked with the PS2 and now represent only a small fraction of its global market.

Nintendo’s home base remains a significant market for its products.

It’s reasonable to ask, however, why this math doesn’t seem to add up in other markets as well. The affordability crisis is hardly unique to Japan, and while there are certainly some countries that have weathered current economic conditions better than others, consumers in most of the world are feeling pretty bruised and battered by price inflation in recent years. The decline of the Yen is a Japan-specific factor, certainly, but it also doesn’t look likely to resolve itself any time soon, which could mean companies like Sony committing to a permanent strategy of cheaper, Japan-locked products.

Presumably, there is a spreadsheet and a bunch of graphs somewhere within these companies where they have modelled the impact of these price cuts and figured out that they make financial sense. Consoles are, in theory, sold on the “razors and razorblades” model; you sell the console as a loss leader and make your money selling software.

This model has definitely been knocked around a lot in recent years – note that Valve seems to be swearing off it entirely for the Steam Machine, asserting that the system will be priced in line with similarly specced PCs, and thus presumably not subsidised in any way. These cheaper Japanese models, however, represent a major re-commitment to that model by Nintendo and Sony.

We don’t see exact per-unit numbers, but PS5 and Switch 2 are likely being sold at quite a discount to their cost of manufacture in Japan – and the platform holders, though they only moved to that model when their arms were twisted very hard by the economic situation, have no doubt satisfied themselves that they’ll still turn a profit in the end thanks to their cut of software sales, subscriptions, and other revenues from console users.

So why only do this in Japan? If the model works in Japan, why not apply a similar pricing approach to try to grow the installed base in other countries as well? A dramatic price cut may not be justified everywhere (though as hardware like PS5 gets increasingly long in the tooth, the fact that it’s as expensive if not more so than at launch undoubtedly weighs heavier and heavier on its market reach), but at the very least this calls into question the justification for the price hikes we’ve seen in the past couple of years.

One reason may simply be that platform holders are very, very nervous about committing to aggressive pricing strategies in the face of massive instability in the cost of key components for these devices. A few years ago, crypto mining drove the prices of GPUs through the ceiling; now it’s the turn of high-speed RAM and SSD chips, which are essential for building out AI datacentre capacity and have soared in price in recent months, with RAM prices doubling, trebling, or even in some cases quadrupling in the space of just a few weeks.

For anyone trying to build or buy a PC right now, this is a gigantic pain; for a console manufacturer trying to lock in a competitive price point for millions of units of hardware, it’s an absolute nightmare. While a company like Sony orders these components in enough bulk to get some price setting power, it’s not immune to more long-term swings in pricing – which could easily turn some key numbers in its business models a very bright shade of red.

Hedging against those possibilities no doubt makes companies like Sony more conservative on pricing strategy, and far less keen to take on the risk of treating its consoles as a significant loss leader.

However understandable that may be, however, it still leaves us with a reality where consoles are expensive – far from falling in price over their lifespans as they once did, they are instead getting price hikes in many cases. In essence that means that the market dynamic whereby consoles would drop to impulse-purchase prices after a few years and open up whole new consumer demographics in the process is gone. It’s no coincidence that a lot of the casual, family-friendly genres of game that were so successful on platforms like the PS2 and the Wii have either moved to mobile devices or faded out entirely.

Consistently high platform pricing has killed off family games that flrourished in prevous generations. | Image credit: Sony Computer Entertainment

This whole situation demands consideration of a very key question; what is the role of a platform holder in this industry? A few console generations ago, the answer was straightforward; they were the lynchpin of the industry precisely because they were the companies willing to take on the massive financial risk and burden of establishing a console platform and building a market for it. In doing so they took on the responsibility of creating and growing the marketplace for other publishers and developers – repaid, in turn, by taking a pretty healthy slice of revenue from each game those third-parties sold.

Console manufacturers still take on the risks and costs of creating and selling hardware, and they build digital services platforms and other infrastructure around their devices – all of which does provide a benefit to everyone else in the industry. However, it feels that they’ve lost much of their appetite for the core task of actually building and growing the market – that they’re no longer willing to take the risks and put in the work required to reach new markets and push their devices out beyond their (admittedly very large) core consumer base.

Japan’s consumer price sensitivity may be relatively high, but it’s not unique; it’s simply the canary in the coalmine for trends that are replicated in markets all around the world. If Nintendo and Sony are willing to put their backs into building the Japanese market by slashing their hardware margins and taking on greater financial risks – and if they can still make money while doing so – then it’s hard to see why the same approach isn’t justified in other markets too.

AloJapan.com