TOKYO – As Gaza begins to recover following a cease-fire agreement between Israel and Hamas, a recent cooking event offered people in Japan a rare chance to connect with the region’s people through food — and to imagine daily life before the devastation.

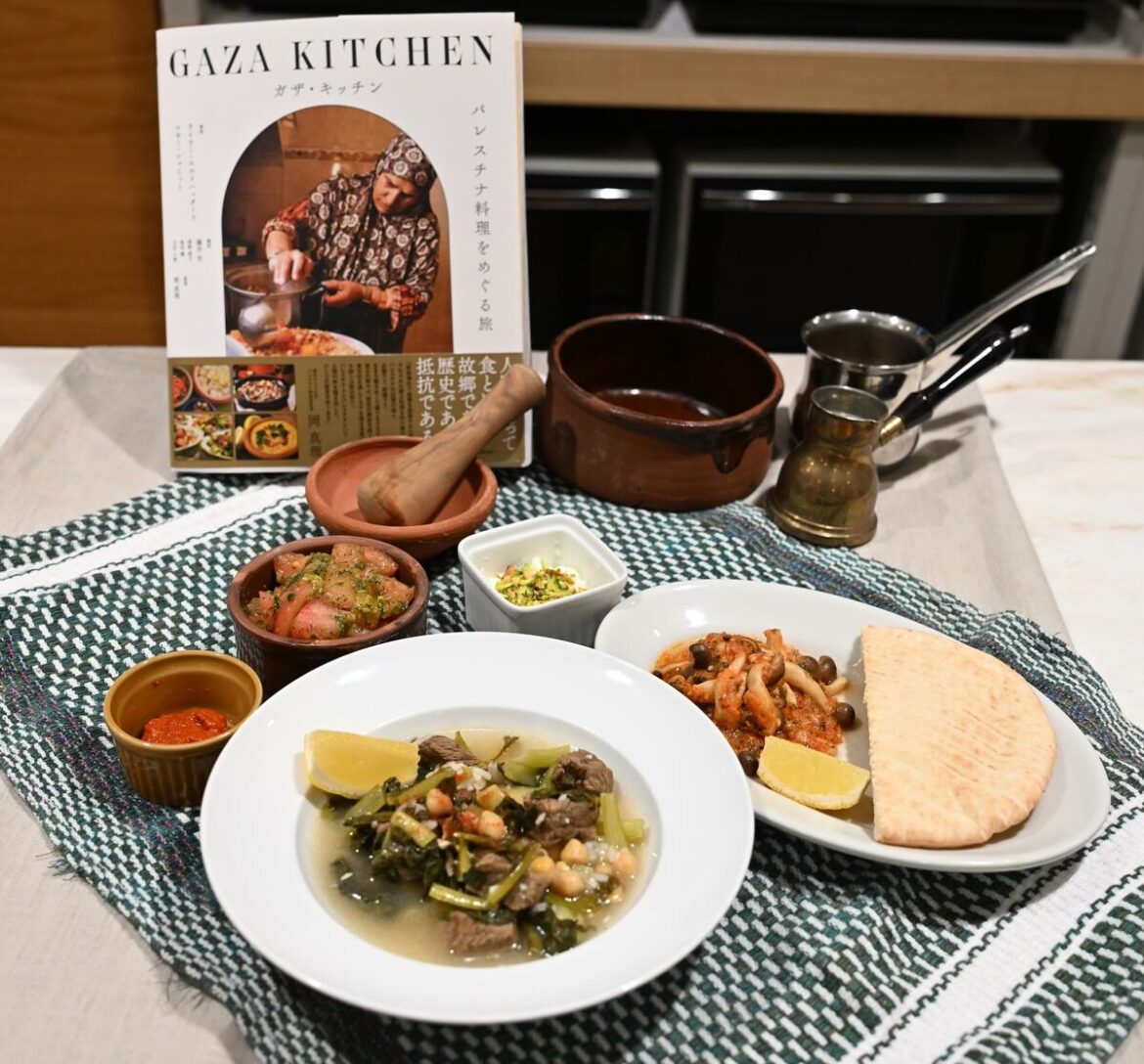

At Koto Laboratory, an experiential learning studio operated by Orangepage Inc. in Tokyo’s Suginami Ward, participants gathered to cook and taste recipes from “The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey,” a cookbook translated into Japanese by the cooking and lifestyle magazine publisher.

Following a well-received first event in July, the second session was held in October, coinciding with the two-year mark since Israel’s invasion of Gaza, which suffered extensive damage during the conflict, with about 80 percent of buildings estimated to have been destroyed or damaged.

Inside the packed venue, Arab confectionery and cooking expert Aki Komatsu, who studied in Syria and Egypt, prepared traditional Gazan dishes using ingredients that are not easy to come by in Japan.

The menu included “fogaiyya” — or lemony chard, chickpea, and rice stew — made with komatsuna Japanese mustard spinach as a substitute for chard, a leafy vegetable that is difficult to obtain in Japan.

Israel has faced international criticism for what rights groups call the use of hunger as a weapon of war, blocking relief supplies and leaving civilians starving. Some attendees said they felt uneasy about eating food from Gaza while residents there still face shortages.

But after listening to an explanation from one of the translators of the book, Hikaru Fujii, associate professor of American literature at the University of Tokyo, and watching the appetizing dishes come together, participants were captivated.

As they shared the meal, a lively discussion followed — part culinary exploration, part reflection on Gaza’s people and culture.

Fujii, known for translating contemporary American literature including Anthony Doerr’s novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” said “The Gaza Kitchen” was his first attempt at translating nonfiction.

“I was shocked to realize I knew nothing,” Fujii said. “I couldn’t imagine what specific aspects of life were being lost.”

“There are many people like me who are interested, but don’t have any concrete knowledge about Gaza,” he said. “What kind of meals did they eat, and how did they eat together? I couldn’t help but wonder, so I began searching, and that’s when I came across the original version of this book.”

“I thought this was a book that everyone should read. I wanted to have a go at translating it,” Fujii said. “I thought we have to act fast.”

Fujii said a translation team was formed with three graduate students, two from the University of Tokyo and one from Kyoto University.

The original English-language book was written by Laila El-Haddad, a writer with roots in Gaza now based in the United States, and Maggie Schmitt, an American-born author living in Spain who specializes in the Mediterranean world.

The book documents the home-cooked meals of Gazans. Since around 2010, the authors have gathered recipes, interviews, and photographs that reveal Gaza’s food culture — from rice and fish dishes familiar to Japanese palates to spiced stews and Mediterranean fare.

The book’s pages capture not only recipes but also scenes of the vibrant streets of Gaza — now largely destroyed.

Fujii said the translation team relied on advice from Mari Oka, a Waseda University professor of Arabic literature, to ensure accuracy. “It was a challenge since none of us had been to the Gaza Strip,” he said.

Historically, Gaza has been a key trade hub linking Africa and Asia. After World War I, it came under British Mandate administration and later Egyptian control following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Refugees from other parts of Palestine increased its population from tens of thousands to about 2.2 million by 2023.

This mosaic of origins created a rich and diverse culinary heritage. Oka describes Gaza’s cuisine as “a museum of Arab cooking.”

Tokyo-based Orangepage said the project was intended to share food culture beyond Japan.

“As a food magazine, we believe it is our mission to introduce what people are cooking in homes around the world,” said editor Kei Okano.

While some of the Gazans featured in the book are believed to be missing or dead, Fujii described the collection of family recipes as “a form of living testimony literature.”

The book, priced at 4,950 yen (around $32), has received domestic media attention and has been added to many public library collections.

One participant at the Tokyo event said the experience helped make the distant conflict feel more personal.

“I always thought Gaza was a faraway place I saw only in the news. Learning about its food made me feel closer to the people who live there.”

In a world divided by politics and distance, “The Gaza Kitchen” offers a reminder that shared meals can bridge understanding.

For some, the book is simply a collection of recipes. But for others, it’s a quiet act of connection — one that helps restore the image of a city where, despite hardship, families once gathered around tables to enjoy good food and each other’s company.

AloJapan.com