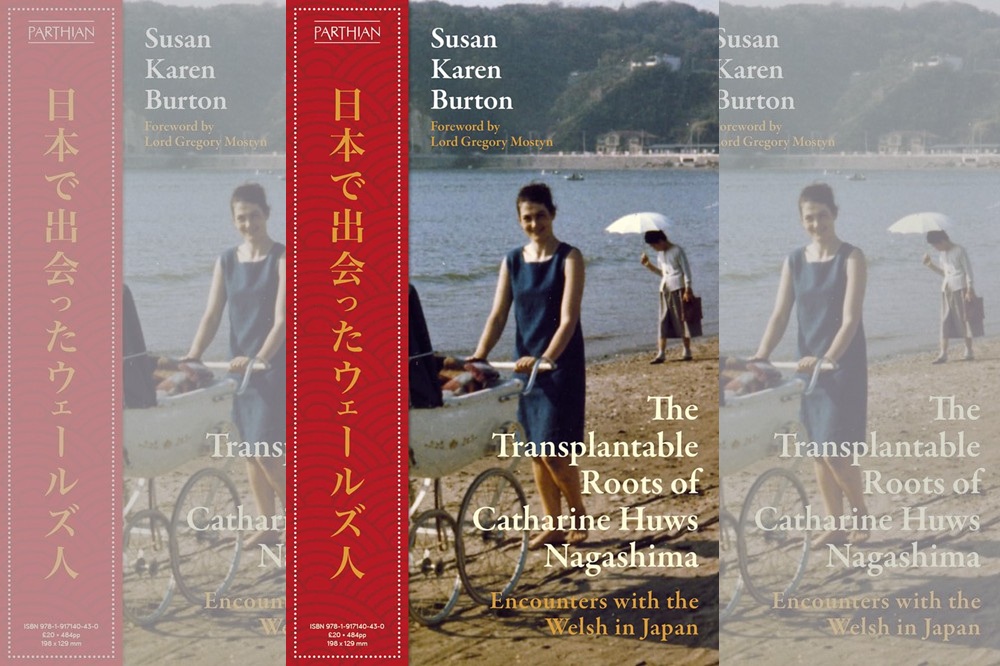

The Transplantable Roots of Catharine Huws Nagashima is published by Parthian

The Transplantable Roots of Catharine Huws Nagashima is published by Parthian

Desmond Clifford

This book is a collection of interviews with Welsh people living in Japan. They are a diverse bunch including ecologists, writers, translators, farmers, video game entrepreneurs (coal to Newcastle, surely!), architects, martial arts instructors (more coals), ski instructors, film directors and a good number of teachers.

They all seem to love Japan, even when alert to the difficulties living there as a foreigner. Their testimony about Japan is mostly positive, but some themes emerge.

Isolation and a degree of loneliness is a repeated problem. The Japanese people are polite and helpful, but their society is radically different from Wales and outsider status is hard to overcome.

Loneliness is reportedly a problem for Japanese people too. Clearly much depends on personal circumstances. Migrants who are married into Japanese families have access to social integration not easily available to those who are not.

In any case, Japan has an unusually small number of foreigners relative to many developed countries and its culture emphasises Japanese distinctiveness as something to be prized and protected, notwithstanding a wholesale adoption of the veneer of American cultural values in the post war period.

2025 is the year of “Wales in Japan”, an officially sanctioned project of celebration of links between the two countries. Wales and Japan lie at either end of the archipelagos off the east and west ends of the Europe-Asia land masse. Slightly short of 9,000 miles separates them.

At first glance you might think they’re unlikely partners. Japan’s population is 41 times bigger than Wales. Japan’s economy recovered quickly after some difficult post-war years and by the 1980s it was at the centre of a global boom in cars and electronic devices.

It was the world’s second largest economy and presented long-term challenge to American global dominance.

In the early 90s the economy over-heated and Japan entered a long period of stasis, not unlike Britain’s now. The digital revolution passed it by, and the innovation lead reverted to America, leaving a weakened Japan uncertain of its position in the world. China’s rise has only exacerbated that sense.

Japanese investment

The contemporary Wales-Japan relationship was built substantially on Japanese investment. Japan’s emergence through the 1970-80s as a global manufacturer, with an enviable reputation for quality and precision, was mirrored in Wales by the definitive winding down of the heavy industries which had sustained the country since the dawn of industrialisation.

With Wales inside the European Union, it was a good tie-up. Takiron opened in Bedwas in 1972 and was soon followed by a host of familiar names: Hitachi (Hirwaun); Sony (Pencoed and Bridgend); Panasonic (Cardiff, Gwent, Port Talbot); Toyota (Deeside).

Japanese investment into Wales became something of a stereotype for the WDA in its 1980s pomp. At one stage, some 25% of all Japanese investment into Britain was located in Wales, with just 5% of the UK population. It was a success story (with the caveat, at risk of a bum note, that it should also have been accompanied by a strategy for stimulating sustainable domestic Welsh industry, which didn’t happen at the right scale).

Although industrial connections created a context for Wales-Japan, most of the people featured in this book found their way to Japan out of simple curiosity.

It is indeed a fascinating place. I remember on a visit to Tokyo walking along a six-lane highway opposite the Imperial Palace, surrounded by skyscrapers. Although it looked like lots of modern cities, I noticed a major difference: no excess noise. There was the hum of car engines but no horns blasting, no intemperate shouting.

Taxi drivers wear gloves and tipping is deemed offensive; you pay for the service you get and no more is required or wanted.

There is no official figure for Welsh people living in Japan but it’s probably about a couple of thousand. Many of these are teachers or students who will probably return home eventually.

Doyenne

The long-termers are the most interesting part of this book. Catharine Huws Nagashima, after whom the book is named, might be viewed as doyenne of the Welsh settlers. She moved to the seaside town of Zushi after a childhood in Talwrn, Ynys Mon.

She met and married Mr Nagashima and returned with him to Japan in 1965. It was a period of relative opening-up for Japan. The 1964 Olympics (of “Lynn the Leap” fame; Lynn Davies of Bridgend won gold for the Long Jump) signalled Japan’s post-war rehabilitation.

The Beatles were first among a long line of stars to play at Budokan stadium (when I was young, imported Japanese imprints of Anglo-American records had high status).

Catharine Nagashima records the strangeness of adjustments to Japanese life. There were few westerners and contact with “home” was expensive and slow. Cards and magazines sent by sea could take weeks; there were no international phone calls.

She maintains that growing up with a strong sense of place – Wales – helped her adopt a parallel relationship with Japan. She became active as an environmentalist and had six Japanese children; dual passports are not allowed in Japan after childhood.

She visits Wales still but has now lived sixty years in Japan.

Not every experience works out with such stability. All around the world expats can become, without having intended it, “trapped” by what started out as an exotic experience.

Andrew, from Pentyrch, records experience of uncertain status arising from divorce and the often-limited career horizons for language teachers moving from contract to contract in a saturated and transient market.

Uncertain status

A few years of post-graduate adventure can turn into decades of grinding a living and lost opportunities on the home front and, before you know it, a mid-life conundrum about options ahead.

In this respect, life in Japan is not dissimilar to expat experience generally.

Unsurprisingly, most people find they can’t integrate into Japan, or even work outside of teaching jobs, without learning Japanese. It’s a difficult language for an English speaker, not least because it has three written forms.

On the other hand, interviewees testify that fluent English is relatively rare in Japan so Japanese language immersion is viable and available, if not unavoidable. This is unlike European languages where, these days, English is often so prevalent that real motivation for language learning can be a challenge.

A number of interviewees found Japan a source of inspiration for their creative output, including writer Eluned Gramich and film-maker John Williams.

It sometimes feels phoney when people bend experience excessively to demonstrate what two countries have in common. It is the difference which makes them interesting and enrichening.

Among Japan’s long-term traits is resistance to foreign influence. Japanese culture is prized above all.

Nothing wrong with that, but it sounds like this can be wearying for people coming from Britain’s more amorphous traditions.

Migration

Japan has a long tradition of discouraging migration and Europeans may have a happier story than, say, Koreans, who historically have had a tough time in Japan (one of this year’s Booker Prize entries, “Flashlight” by Susan Choi touches this very topic).

Women have not been fully recognised in the workplace in Japan and senior female executives are rare. Japan is trying to change this and recently its first female Prime Minister was voted into office.

At any rate, Wales and Japan have found things to do together – business, trade, tourism, culture and rugby.

By chance, I was at the Tokyo rugby game in 2013 where Japan beat Wales for the first time, and very sobering it was too. Our Japanese hosts refrained from celebrating in front of us, constrained by the respect and humility which is key to their culture.

I imagine they wanted to run around making a hand gesture off their nose shouting, “Beat you, suckers!” Perhaps that’s what they did after we’d gone.

This book, by Susan Karen Burton, is in the oral history tradition. It will obviously be of interest to people looking for insight on Japan and its culture. By all accounts, that’s a growing number since Japan’s popularity as a tourist destination has increased markedly in recent years.

It’s surprising, perhaps, that the book fails to draw more on the substantial industrial connection which has been so significant during this last half a century.

In receptions at the British Embassy you meet aging executives who talk with passion about their times living in the suburbs of Welsh factory towns, and indeed, their opposite numbers from Wales who spent extended periods in Japan studying its industrial culture.

Those connections are diminishing somewhat now as investment patterns shift and (ahem) Brexit locks Wales out as an EU investment location.

Increasingly, teaching and creative industries seems to be the main basis for the continuing Wales-Japan connection.

The Transplantable Roots of Catharine Huws Nagashima is published by Parthian and can be purchased here and at all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an

independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by

the people of Wales.

AloJapan.com