When Japan modernised during the Meiji era (1868–1912), the government banned tattoos in 1872 to project a “civilised” image to the West. Though legalised again in 1948, the yakuza (Japanese crime syndicate) later adopted full-body tattoos as part of its uniform, preserving Edo notions of group allegiance while cementing tattoos’ association with organised crime. That image, reinforced by yakuza films of the 1970s, still lingers in public spaces like baths and gyms. Yet as Japan welcomes more foreign visitors, younger generations are adopting more global attitudes, and old associations are beginning to fade.

Contemporary Japanese tattoo culture

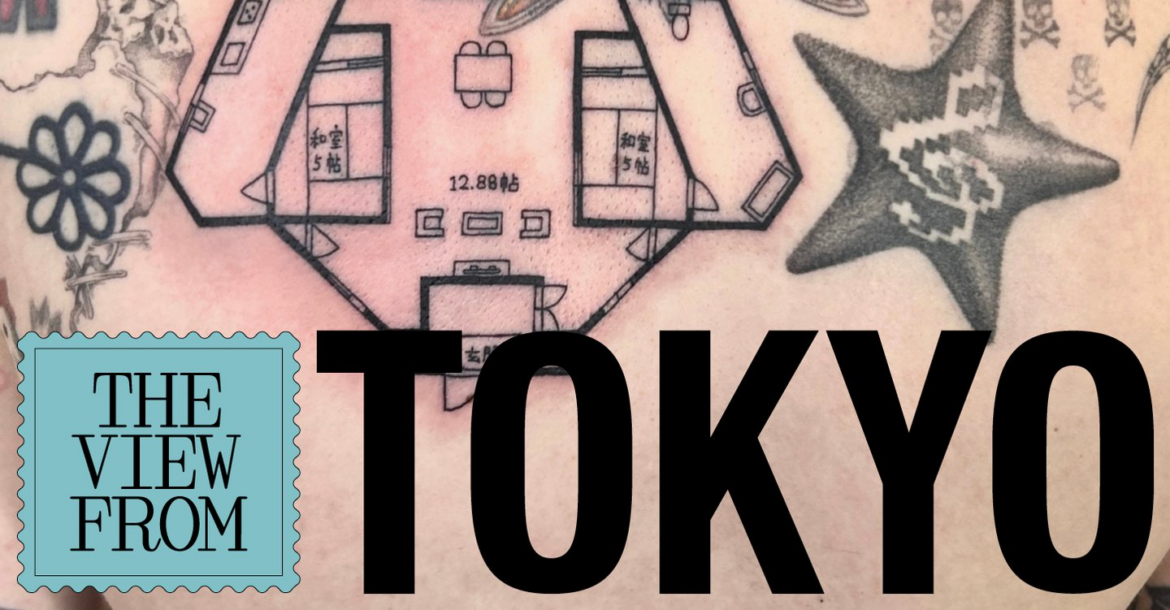

While the legacy of stigmatisation still remains in the public imagination, a new generation of Japanese tattoo artists is expanding the meaning of inking one’s body. Some mix styles across cultures; others pare them down to a single dot. For younger people, there’s now a clearer distinction between irezumi – traditional tattoos linked to the yakuza – and Western-style “fashion tattoos”. Makeup artist Yuuivision, who worked at a tattoo-friendly bathhouse, notes that younger customers rarely minded tattoos, though she occasionally received grievances from older customers who lumped irezumi and fashion tattoos together. Artist Coca adds, “I used to get stopped by the police for having visible tattoos. That happens less now, but traditional irezumi will probably always carry a sense of fear.”

As attitudes toward tattoos slowly shift, some artists are exploring that tension through subtlety. Graphic designer Ayaka Katayama, who wears a small pink dot by artist Hanae Sato on her earlobe, introduced me to Hanae’s 1mm Tattoo – an art project that turns tattooing into a quiet meditation on individuality and universality rather than body decoration. Using the body as her medium, Hanae inks a single one-millimetre dot, small enough to be mistaken for a freckle, across a growing community of thousands spanning generations, nationalities, and regions. Each mark reflects time and change, bound to the body that carries it. Because of its minimal, nearly invisible form, it reverses the usual gaze of tattooing: instead of being made for others to see, it belongs to the wearer alone. “It’s like a secret luck charm,” Ayaka tells me. Though Hanae doesn’t identify as a tattoo artist, her work bridges art and body modification, linking individuality and universality through the shared experience of being human. Rooted in diverse urban cities like Tokyo, Hanae’s 1mm Tattoo quietly expands the perception of tattoos in Japan.

AloJapan.com