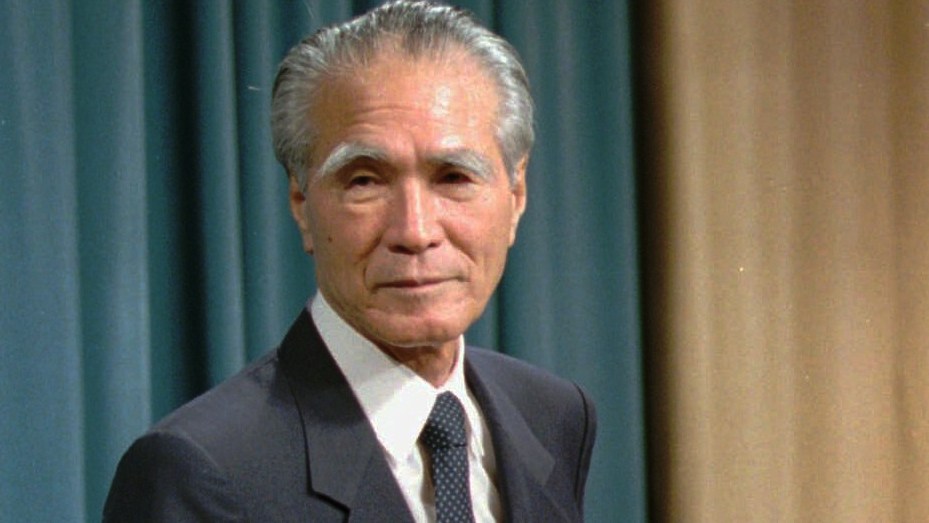

At first glance, little in Tomiichi Murayama’s background seemed to have prepared him to lead Japan’s 81st government. He was the modest, quiet son of a fisherman, and a passionate socialist during a period of irrepressible conservative nationalism. The press referred to him as the “good grandpa” and often made more of his characterful eyebrows than his political record in the lead-up to his election.

During his brief, 18-month premiership, however, Murayama would face some of the country’s most historic crises and take steps to repair international relations that had been ailing since the end of the Second World War.

The centrepiece of his foreign policy, and his most enduring legacy, was the 1995 Murayama Statement, a landmark commitment to reconciliation between Japan and the countries it fought and persecuted between 1931 and 1945. Murayama had to fight to get it past his coalition cabinet, which reluctantly endorsed a severely edited version of the speech only after the prime minister threatened to tender his resignation.

In the impassioned statement, delivered on national television on August 15, 1995 — the 50th anniversary of Japan’s Second World War surrender — the prime minister acknowledged that the country’s wartime actions had “caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries”. He believed that Japan needed to take positive steps to address its darkest historical legacies: “I regard, in a spirit of humility, these irrefutable facts of history, and express here once again my feelings of deep remorse and state my heartfelt apology.”

Reactions to the statement within Japan were initially mixed, but western and Asian nations, including South Korea and China, praised Murayama for breaking the mould of previous postwar Japanese prime ministers. They recognised his genuine belief in reconciliation and his deep commitment to coming to terms with the devastation Japan’s pre-war and wartime actions had wreaked across east Asia.

Tomiichi Murayama was born in 1924, the seventh of 11 children, in Sumiyoshi, a fishing village in Oita prefecture on Kyushu, the southernmost major island of Japan. Most of his primary school classmates were sent straight off to work in a country racked with economic privation, but Murayama moved from Oita up to Tokyo, a far-from-easy journey in the midst of the Pacific War. There he worked during the day and attended evening classes at Tokyo Municipal School of Commerce before earning a place at the city’s Meiji University.

Murayama reviewing Japan’s self-defence force in 1994. He faced conflict with anti-war members of his Japan Socialist Party

AP

He began studying at the faculty of politics and economics in 1942, and in 1945 he witnessed the devastating firebombing that destroyed a quarter of the capital’s buildings and killed an estimated 94,000 people. The war left Murayama a committed pacifist and a socialist.

He sought and eventually won election to Oita city council, and in 1955 joined the newly reconstituted Japan Socialist Party (JSP). After three successive terms in office in the Oita Prefectural Assembly, Murayama progressed beyond local politics to fight and win a seat in the Diet, Japan’s parliament. He gravitated to the social and labour committee in the Diet, where he showed a strong interest in labour issues, welfare, pensions and health, and was involved in efforts to combat Japan’s emerging Aids epidemic.

The JSP was offered an unlikely coalition in 1994 after the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) — which had dominated Japanese politics almost continuously since 1955 — lost its majority for the first time in nearly 40 years. The LDP would remain the largest power in the cabinet, but in return for its role in the coalition the JSP would be able to name a premier. Murayama was made leader of the JSP in 1993, and so it fell to him to helm the fragile new partnership as prime minister.

From the start, he was not expected to survive long in office. Financial markets were still reeling from the recent asset price bubble. Then in January 1995, only six months into Murayama’s term, the Great Hanshin Earthquake hit. It destroyed 150,000 buildings, killed more than 6,400 people and left 400,000 more without gas, water or electricity. Estimates of the losses and damage caused by the earthquake exceeded £140 billion, or 5 per cent of Japan’s GDP, making it the most expensive natural disaster in history at the time.

The prime minister visited the affected area and, despite his experience of wartime bombings, he was overwhelmed by the scale of the devastation he witnessed. The government’s slow response to the crisis and its refusal to accept international offers of technical rescue services were later widely criticised. Particularly damning was the discovery that a yakuza syndicate had taken on the role of distributing food and supplies in the absence of any proper government aid response directly after the quake.

Murayama visited to Kobe after it was devastated by an earthquake

AP

Less than three months later, in March, another disaster nearly overtook the government when the Aum Shinrikyo sect launched a sarin gas attack on the Tokyo underground railway system. Thirteen people died and more than 3,000 were injured in a co-ordinated assault on five underground trains, the deadliest terrorist attack in the country’s history. After a seven-month police investigation, Murayama’s government ordered the dissolution of the sect, but once again was criticised for doing too little too late.

On foreign policy, however, Murayama was already proving progressive and decisive. After meeting with distrust and “hard looks” on early diplomatic visits to South Korea and China, the new prime minister had become committed to improving his country’s postwar relations.

The Murayama Statement heralded the beginning of a ten-year, 100 billion yen “peace, friendship and exchange initiative”, a programme of collaborative historical research and international exchange programmes conceived in the hope of promoting dialogue and mutual understanding between postwar nations. In Britain, the initiative manifested in the form of a five-year Anglo-Japanese history project, which surveyed 400 years of relations, and a programme of subsidised trips to Japan for British ex-prisoners of war, as well as their families.

Murayama also established the Asian Women’s Fund, providing compensation and welfare provisions for those termed “comfort women” during the war, women — primarily Korean — who had been forced into sexual slavery in the service of the Japanese armed forces.

Murayama in 2015. He continued to defend the legacy of his statement as from conservative governments sometimes sought to undermine it

TORU HANAI/REUTERS

Domestically, he continued to introduce economic and social reforms, including increased support for children, the elderly and the disabled, though he failed to break the country out of its lingering recession. On some fronts he reluctantly made concessions to the LDP base of the coalition, such as the country’s retention of a self-defence force. This contravened JSP dogma, which took a strict view on the pacifism article of Japan’s postwar constitution, and, rather like Ramsay MacDonald in Britain, Murayama was accused by many of betraying fundamental party principles, leading to large schisms within the party.

He resigned from his post in January 1996 in accordance with the coalition’s terms for a rotational premiership. The now increasingly divided and disorganised JSP requested he stay on as party leader, which he did until March 2000, at which point he announced that he intended to retire from politics completely, citing his age (he was now 76), his diminished physical capacities and a decreasing “spiritual drive”.

He married his wife, Yoshie Murayama, in 1953 and they remained together until her death last year. He is survived by two daughters, Mari Murayama and Yuri Nakahara.

After his resignation, Murayama became president of the Asian Women’s Fund and carried on actively promoting Japanese relations with South Korea and China. Meanwhile his successors continued to reaffirm and quote from his statement on each new anniversary of the end of the war. On the very few occasions that they attempted to qualify or contradict it, Murayama made sure his voice was heard all the way from his retirement in Oita: “All of us must refrain from words and deeds that will trigger conflict,” he warned in 2013. “I oppose any revision to the statement. Japan must continue abiding by its spirit.”

Tomiichi Murayama, Japanese prime minister, was born on March 3, 1924. He died on October 17, 2025, aged 101

AloJapan.com