Japan is hardly known for placing limits on cinema; one might posit that young cinephiles largely enter the nation’s incomprehensibly dense corpus through its most extreme offerings. While most accurately called an American project, almost universally hailed as a masterpiece, and hardly extreme in content––it takes a comparatively tame place among the director’s own oeuvre––Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters went 40 years without official appearances in Japan. A cursory understanding of Yukio Mishima’s life, art, and enduring legacy would help sketch the not-quite-official-but-good-luck-trying ban, whatever ambiguities about its notably distended enforcement persist. But the point remains: Schrader’s many-headed biopic, a rep-house regular that’s streamable on the Criterion Channel this very moment for those of us in North America, remained something like contraband in its country of production until this past Wednesday, despite future distribution remaining a tad unclear.

The Tokyo International Film Festival’s typically reserved audiences generated unusual levels of pre-screening energy in Ginza’s cavernous Hulic Hall––perhaps rumors I’d heard of a potential disruption trickled down and carried weight––though an extended introduction from Schrader, producer Mata Yamamoto, and associate producer Alan Poul entirely comprised appreciation and sentiment. And while some reservation carried through a viewing of the film––not that Mishima strives for responses in the same key as The Naked Gun––subsequent applause sustained for some time as Schrader paused at the theater’s exit to acknowledge a first-ever Japanese audience. (His fear, expressed below, that native viewers would take poorly to certain subtleties proved unfounded.) Warm feelings carried into the evening’s afterparty, the filmmaker received by decades-old collaborators (among them Yuki Nagahara, the one-time actor who portrays a five-year-old Mishima but had never seen the film until that afternoon) and sundry figures of the Japanese industry.

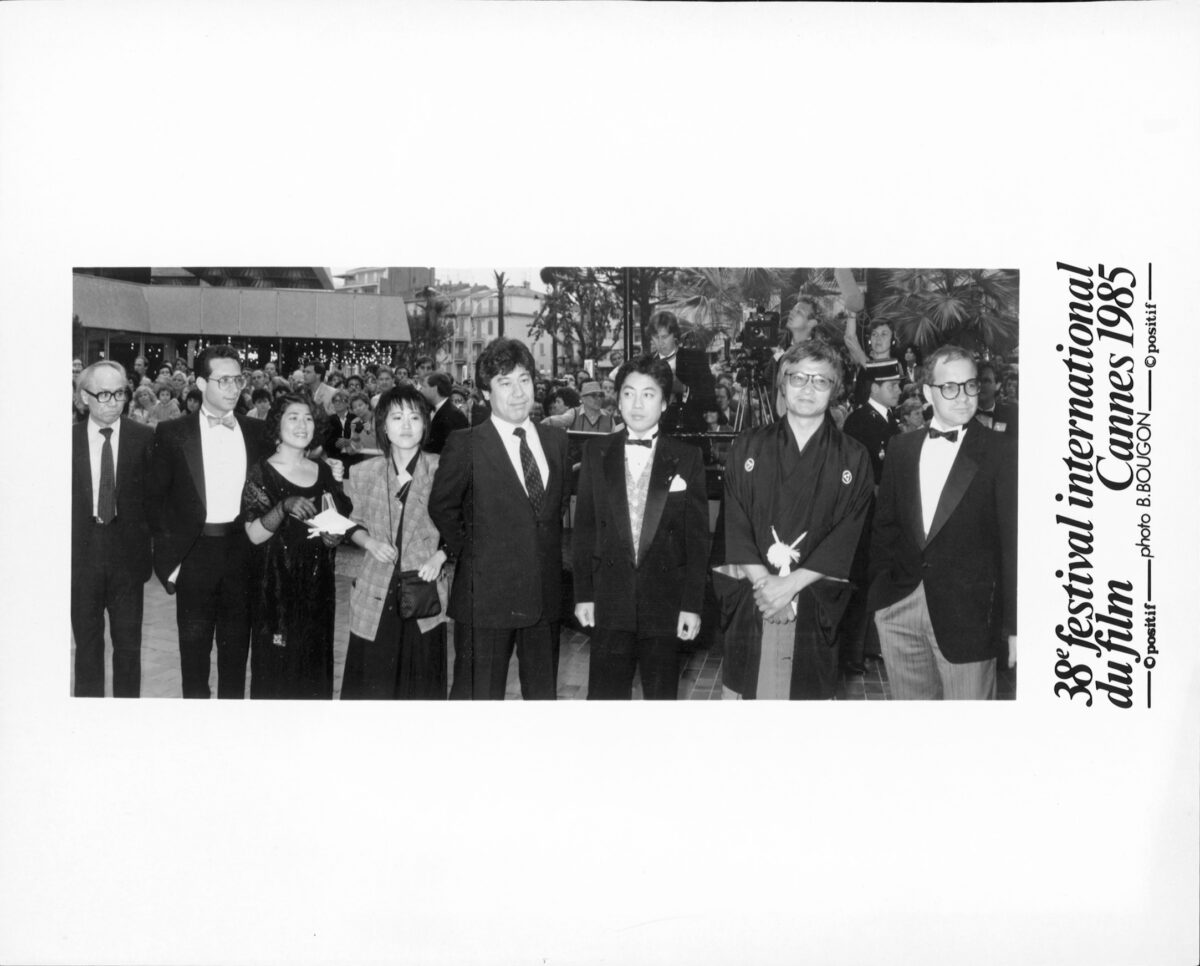

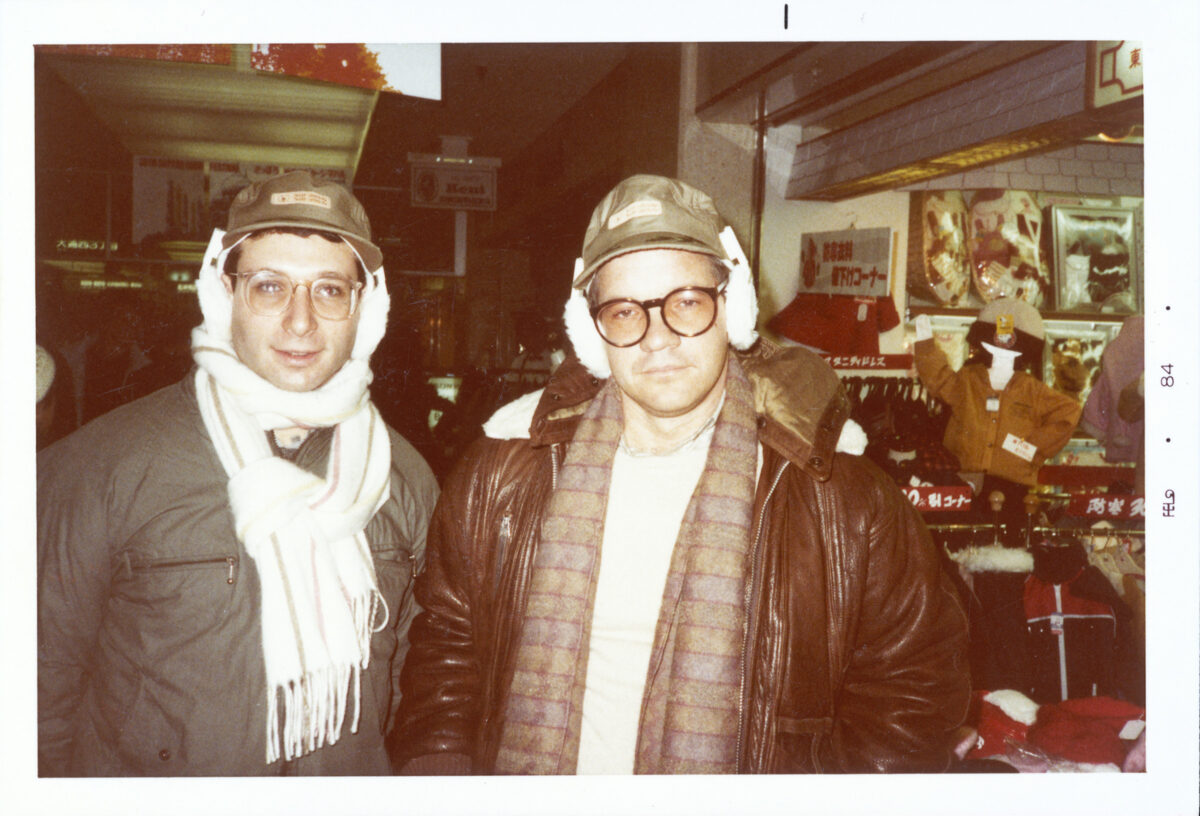

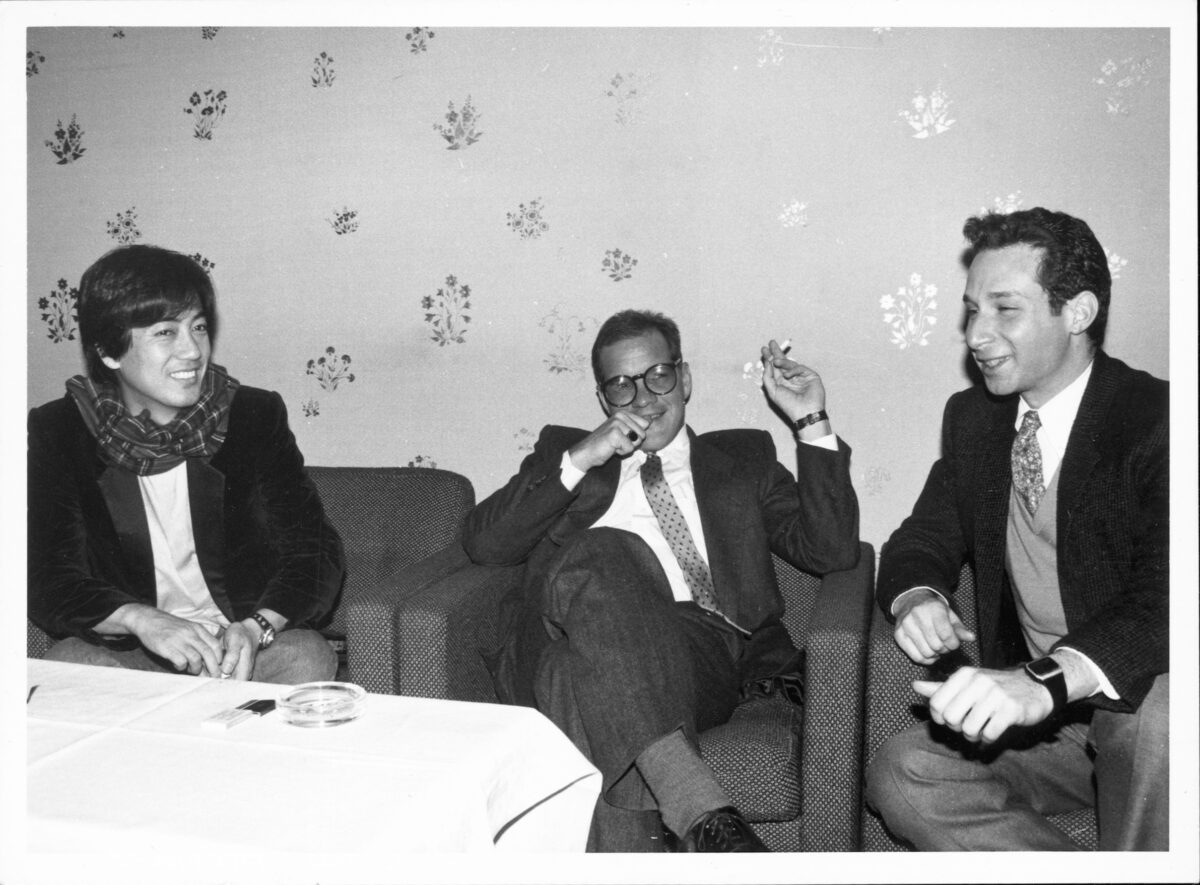

I met Schrader a day prior to Mishima’s premiere for a discussion of the film and its peculiar rebirth. (Poul joined us but, minus one funny observation, remained silent.) I’ve already sat in on two screenings of Schrader’s next project, The Basics of Philosophy, some spoiler-free talk of which is peppered throughout. Our conversation––plus exclusive photos from Mishima’s production and premiere, featuring Schrader, Poul, and co-writer Chieko Schrader––follows.

The Film Stage: It was fun watching Basics twice two weeks apart and picking up on changes––some very small and others that were, I would say, a bit stronger.

Paul Schrader: And now it’s up to a whole other level because the music is not the tempo track. Eli Keszler did the music. Quite aggressive and quite original. And rather than fight it, I would say, “Okay, I didn’t see that coming.” [Laughs]

I’m excited to hear it.

I think it just makes it more three-dimensional.

It’s funny, seeing you there and then seeing you here about two films that… I feel like I have an inclination to call them very different, but I also wonder if there are things that are kind of shared between them.

Well, the thing that ties them all together is, you know, how I began, with Taxi Driver and this idea of this lonely sort of fella––keeps his own company, meditates in his own thoughts, and wears a mask, and his mask is his profession. And that idea evolves from attacking a taxi driver to a gigolo to a drug dealer to a poker player to a gardener to a philosophy professor. Mishima is a little different from that, in that he’s a historical figure. But he is a kind of historical figure I would have made, created as a fictional creation if he didn’t actually exist.

It’s sort of divine that he was there for you to use.

Yeah. [Laughs]

You’ve been very honest about calling it the best film you’ve directed.

I’m not… I’m not sure. I think it is the one I was proudest of just because it is so damn unique. I think Affliction and First Reformed are probably the most complete, solid films I’ve made, and Light Sleeper is probably the most personal to me. But Mishima has a place just because it is so outrageous. I still can’t believe it got made and I still can’t believe that I made it.

I’m a great admirer of so many of your films, but you are right that Mishima doesn’t quite have an analog or a one-to-one in your filmography. And I think it’s interesting that it exists in that way and you didn’t necessarily pursue it again. You didn’t try to make another film about an artist that has that…

Well, I did and I quit. This is how it all came about, which is: I wanted to write another one of these lonely guys. And I was doing a biography for Warner Bros. on the life of Hank Williams, who died at 29, who had a bad back, was very morose, depressed, and hooked on morphine because of his back, alcohol. And I was trying to contort his life into Travis Bickle’s life; I was hammering a square peg into a round hole. He didn’t want to die. [Laughs] He wanted to live. Whereas Mishima knew he was going to die years before. And the film we saw that he made in ’64 [Patriotism] is all about his suicide.

So I realized that a human life does not necessarily conform to these––except when somebody accused me of exploiting the Travis Bickle character. He said, “You’re writing down to him. He’s ignorant. He’s unlearned. He’s in the grips of this pathological thinking. But that’s just because he’s so dumb.” And I said, “No, this pathology is not limited to the uneducated.” He said, “Well, give me an example,” and Mishima’s name jumped in my head. I said, “Well, there’s the example right there.” Other side of the world, successful, famous, achievements, political, married, homosexual––same pathology. [Laughs]

What makes the film so extraordinary is that it doesn’t feel like a foreign director going to a country, wearing clothes that don’t fit, trying things they don’t get. And I think that left me, even knowing Mishima’s history, surprised the film had not been shown in Japan for 40 years. And there’s the story about how the woman at Toho said to you at a party, “We had nothing to do with that film.”

Yeah, Kawakita. And that’s when I first realized that something was up, because Toho had a party at Cannes advertising their films at the Martinez. And Mishima wasn’t on the list of films they were talking about it. It was their film. Something’s up! [Laughs]

I think it is a film that could fit into a great tradition of Japanese cinema despite being made by an American. What was the feeling of the film never being shown in Japan? If that was a difficult thing for you, or if it was…

Well, as I just said: I knew something was up at Cannes when Toho was not promoting the film, even though they had financed it. So I knew something was squirrely, so I wasn’t that surprised when it came down that there would never be an official release. And you know… it was kind of cool, in a way, to have this asterisk. The Hollywood Reporter called it a “lacuna of Japanese film history.” You know? [Laughs] This sort of Mishima asterisk. Now they’ve taken him off the asterisk; now it’s not so special anymore.

Given the significant controversy he can still engender, I suppose if the film had been screened in Japan and was well-known, that might mean that you hadn’t portrayed him honestly, that you had soft-pedaled him.

Yeah. And the Japanese, I think they now know better, but at that time they thought he was political. They thought he was a right-wing pro-imperator, all this stuff. I think Ichigaya was his last stage production. I don’t think for a second he believed it was going to start a revolution.

Right.

So the Japanese, it took them a while to understand that this political braggadocio and homosexual braggadocio were not political or sexual as much as they were aesthetic. And I think that’s where I got fortunate as a gaijin––because I didn’t see him from inside the prison box of Japanese history and society.

I know that you had spent some time in Japan prior to making the film. Of course your brother, Leonard, had lived here for a long time and wrote some amazing films. I wonder if making a film in Japan under these circumstances was a source of inspiration for the experimental form.

I remember that being one of the happiest years of my life. My daughter was born here, I came over here, and we had friends in not only the Japanese film community, but also the gaijin social community. And we lived right by Akasaka-Mitsuke––once or twice a week, go down to get in the clubs there––and I just remember it being grand old time. I did come back only one time after, which was to do a music video.

One of my favorites.

[Laughs] But I don’t know what happened. I went to Taiwan, I went to Thailand, I went to Cambodia, I went to Korea, I went to Vietnam. But never came back here.

How is it being back?

I’ve been telling Alan the things I’ve noticed: the buildings are taller, the cars are bigger, and the women are whiter. [Laughs]

Three important distinctions. I’m curious about the creative involvement and inspiration of your sister-in-law, Chieko, about whom not a lot is necessarily known. She had helped translate some materials, like Kyoko’s House.

Well, my brother did not speak Japanese. So I had a right arm and a left arm, and I don’t know which one is the right or left, but one of them was Alan and the other was Chieko. Chieko primarily talked to the actors and Alan primarily talked to the crew, although there was crossover. That allowed me to move at a faster rate, because while Alan was talking to the crew, I would go over to Chieko; while she was talking to the actors, I would go back to Alan. And then John Bailey had his own operator, [Toyomichi] Kurita. I remember it as being… quite smooth and quite enjoyable.

Because we were doing so many different things on any given day––different film styles, different colors, patterns, different cameras––I remember thinking to myself, “You know, usually when the director dies, they figure out how to finish the film.” And I thought, “Geez, if I die, I don’t know if they would know how to finish this film.” [Laughs] Because, you know, I knew what we were going to do every day, and I think Alan knew it, Chieko knew it. But most of the crew did not know why there were six sets and why we were using this actor, not that actor.

Being Japanese, what was Chieko’s perspective on Mishima––something she might have brought to the film as someone who maybe knew his work more deeply?

No, I think she… my brother went here to teach to avoid Vietnam. And he lost his faith, he lost his marriage, he lost his job. He married a Japanese student and he was in Japan during the Ichigaya. But I think her knowledge of it was really… you’re talking about a Kyoto schoolgirl. So you’re not talking about someone who is sort of in the Tokyo literary loop of Mishima.

I’m very excited to be at this Japanese premiere. Will you be seeing the film?

Yeah. It will be the first time I’ve seen it with a Japanese audience.

Alan Poul: Or basically that anybody has seen it with a big Japanese audience.

Schrader: Yeah, I’ve seen it with Japanese in the audience, but I’ve never seen it––

Poul: Not the same! [Laughs]

Schrader: And so all the subtleties, I’m sure I’ll get whacked a few times with unpleasant surprises––the subtleties of language and line-readings and gestures that mean something to the Japanese that don’t mean something to the Western world.

I see.

And I expect I would sense that tomorrow.

When was the last time you saw the film?

All the way through? Been quite a long time. Of course, I had to sit down with Criterion and color-time it. We retimed it, John Bailey and I, with Criterion. We had done a few things that we were able to correct, because films made in the ‘80s tended to be too bright because they wanted them brighter for television, and often projection bulbs were always dim––they were always lumens low––so they wanted your print a little brighter. Now that we have digital and laser, your prints don’t have to be brighter. So whenever you see some of these films from the ‘80s, you’re like [Puts hands over face] “Whoa!” They were meant to be that bright. [Laughs]

You haven’t made any films overseas in a while. I think the last one was Adam Resurrected?

Uh, yeah. I made two films in Bucharest: Dying of the Light and Adam Resurrected. And then I made two films in Rome, and I made one film in England, and I made one film in Japan. So I’ve done stuff overseas; if I’ve made 20-some films, I’d probably made a third of them outside the country.

Your recent films have been upstate New York, Las Vegas, New Orleans, Kansas City. And Oh, Canada is, I guess, an amalgamation of places.

Yeah, well, you’re talking about tax incentives––Missouri is 40%, Kansas City is another 12%. You know, you spend a million dollars in Kansas City and they give you a million-two. That’s part of the new world of economics, the post-studio world of independent financing: you have to go where the incentives are. And the states compete. Louisiana was the highest for a while; then Georgia moved up; now Missouri moved up. Then what happens is they’ll change government and they’ll downscale again; then another state will step up. So I was going to shoot Light of Day in Detroit and the governor changed hands and the incentive dropped and we moved it to Cleveland.

I think all of those recent films use the environments really well. I’m from upstate New York and I can verify First Reformed is accurate. Basics of Philosophy has these very specific, single-level storefronts. But I wonder if you have a desire, even a wish, to make films in foreign settings.

Well, I have a desire to build. I haven’t been able to build in a long time––probably since Adam Resurrected––and so that means you’re shooting on-location and shooting in real locations. Mishima was built. Adam Resurrected was built. The Comfort of Strangers was built. It’s always fun to build, but it gets more and more expensive and so I have to choose between doing lower-budget and practical locations and making films with final cut––or doing somebody else’s, make things with expensive sets. You know which one I’ll choose.

Yes, of course.

In fact, somebody quoted me from Marty’s documentary and sent me the quote. Apparently Rebecca Miller asked me, because Marty had $120 million to do Irishman––but actually it ended up being much more––and Rebecca asked me, “What would you do with $120 million?” Apparently I said, “Real estate.” [Laughs] I have two films I want to make next year. One is a kind of a brother-brother noir––I’m hoping to do that in March––and the other one is a film of malafemmena, female betrayal. So I still have ideas and I still have life experience.

I feel like I hear the slow study drip scripts that you’re working on, but actually seeing them one after the other––like Non Compos Mentis, the nurse film, the movie for Antoine Fuqua––I can’t even remember all of them. It’s not surprising that you know how to write a screenplay, but: what is your practice that allows you to continue working so prolifically?

Outlining. I don’t write until the outline works. And if the outline doesn’t work, I don’t write the script. So I never write a script that I get stuck on. You’ve seen my outlines. [Pulls out phone]

Sure.

You know, they have everything down to the… yeah, so I have it all there. [Shows me Raging Bull outline] I don’t start writing until this exists. So once this exists, it’s a rather short process because you’ve told this many times and you know what’s going to happen on page 45 or 46. So that’s what speeds up the process. And if the outline doesn’t work, that’s not a bad thing––because you’ve been saved right?

Absolutely.

You’ve figured it out in the outline phase that you didn’t have a movie, and it’s a lot better to figure it out in the outline phase than to figure it out six months into the writing phase.

You’ve also talked about a technique where you’re having breakfast with somebody and start telling the story and then go to the bathroom, and if they don’t ask about it when you come back, it can be abandoned.

Yeah. [Laughs]

I’ve actually stolen that; it’s very useful. So you have a cut of Basics that will be mixed in about two weeks?

Mixed in two weeks, yeah––you know, the final mix. It has a very tricky ending, which is kind of the opposite thing that happens at the end of a movie. So how that twisted kind of thing will play out, we’ll see.

It was fun watching it. I think it was the first-ever screening you did, and the actual gasp at the last shot of the movie, with the cut to black…

[Laughs]

…was a lot of fun.

That’s still there, yeah.

I’d be remiss not to mention Philip Glass’ Mishima score. It’s one of my favorite pieces of music; I feel like there are not a lot of scores that so match the emotional current of the film, like, ever in the history of cinema. I wonder if you have any memories of working with him?

Well, it was scored twice. I originally approached him to do it as an opera, which he had done with Gandhi, Einstein. So I said, you know, do one on Mishima, read the books, blah blah blah. So he did a piece of music that was around 40 minutes long. Music without seeing a foot of film. And he sent that to me when I was editing and, you know, it didn’t work. But I tore it up to shreds––looped it, re-edited it, cut it, and made it hit all the marks I wanted it to hit. Then I went back to Phil and said, “I destroyed your score. Musically, I think it doesn’t work at all, but it does work conceptually. And so I had a listen, and then he listened to it, and then he re-scored it. So that’s how it fits so well, both as a stand-alone piece and as an underscore. And also, in order to get Phil to do it essentially for free, we had to give him music rights. That’s why you hear it in elevators.

AloJapan.com