An upright young samurai, a cross-dressing sword-wielding maiden, a retired warrior, honour killings, killings not-so-honourable, and lovers of all kinds. Welcome to The Samurai Detectives, the first part of a series of popular historical mystery novels by Shōtarō Ikenami (1923-1990).

Originally written as a serialisation in the monthly magazine Shōsetsu Shinchō between 1972 and 1989, the series was published as 16 complete novels under the title, Kenkyaku Shōbai (Swordsman’s Business). Regarded as one of Ikenami’s three signature works, The Samurai Detectives is the first English translation of his writing.

The book opens with Daijiro, a poor but principled young samurai. As he practices his craft alone in an empty field under the open sky, he is offered a huge sum of gold – but at the cost of his honour. Herein lies the crux of the book, where principle and commitment to the warrior code juts up against the temptations and practicalities of living in Edo-era Japan.

Edo-era sleuthing.

Penguin

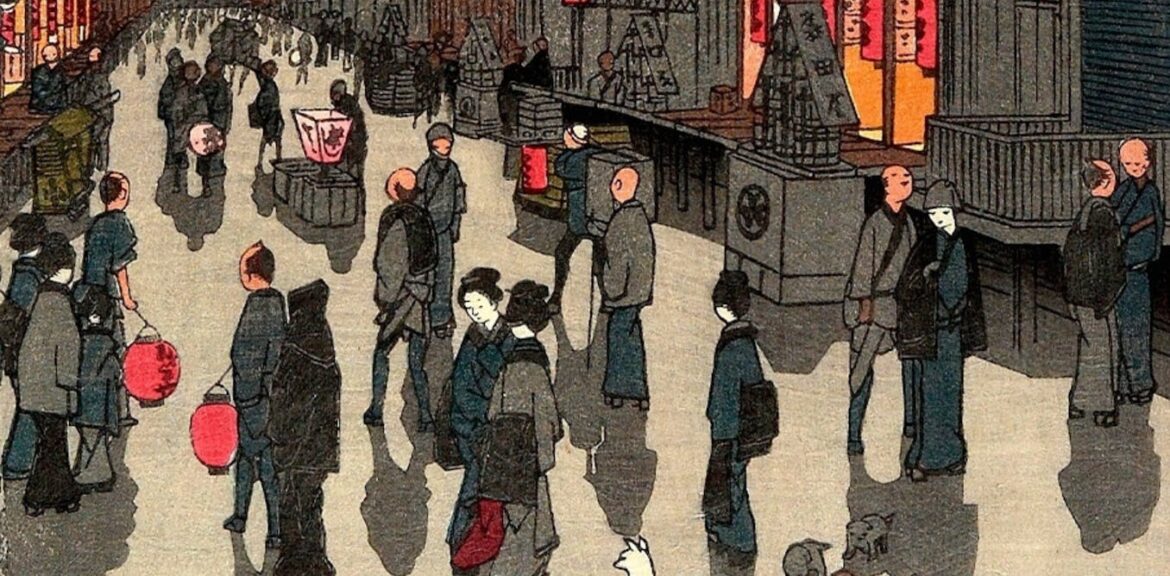

Also known as the Tokugawa period (1603-1868), the country was under the rule of the feudal Tokugawa shogunate. This was a time of peace and flourishing of the Japanese economy and arts, following two centuries of civil war.

Ikenami’s book was published at an apt time. Just as it muses on what to do with the leftover samurai and their skills in an era of peace, so 1970s Japan, following the upheavals of wartime defeat, 1950s post-war and 1960s civil unrest, was grappling with what to do with their post-nationalist militarised society and legions of men.

The answer? To plug it all into their economy. This created what would become the new symbol of Japanese hegemonic masculinity, the corporate worker as “Japanese salaryman”, or “corporate samurai”.

At first, it’s easy to assume that the handsome, upright, young Daijiro is the book’s hero, but as the story unfolds it becomes clear that this is a classic case of misdirection. Instead, other more complex characters come to the fore – in particular, Daijiro’s more pragmatic father. The poetics of the still landscape give way to the dynamism of a bustling Edo metropolis (the city that became Tokyo) and robustness of dramatic – and at times graphically violent – action.

Filled with distinctive characters, shady dealings, women of moral ambiguity, heroes and villains alike, this really is samurai detective fiction. Building on the introduction of detective fiction to Japanese literary fiction in the 20th century, The Samurai Detectives falls between the historical detective and social mystery subgenre.

Throughout the book, Ikenami offers extensive histories of places, characters and their allegiances, emphasising the importance of understanding the interconnected relationships and motivations behind their actions. From explaining the wider politics of the feudal families to the personal histories of the characters, the book takes the reader through the history and social geography of Edo Japan. It draws readers into the complex world of the samurai and their code, bushido.

Yet rather than a simplistic, romantic portrayal of samurai, the stories are underpinned by the tension between the wider samurai code and the characters’ personal struggles. They wrestle with how to align their own desires with their responsibilities and loyalties. This follows the Japanese concept of honne-tatemae, or the tension between private feelings and public behaviours.

Shōtarō Ikenami in 1961.

Wiki Commons

From a high-ranking daughter’s desire to become a warrior, despite the expectations placed on her as a woman in Japanese society, to male samurai pursuing secret relationships with male lovers or adorning themselves with feminine make-up, the book is full of contradictions. It explores the tensions between personal desires and social norms.

Complicating this is the underlying sense of changing times. The warriors must renegotiate their place while the world moves into the complexities of peacetime.

This tension comes to a head in the book’s explosive action. Characters move quickly through changing landscapes, cities, homes and modes of transport, shifting from quiet reflection to dramatic events, creating a constant sense of energy and motion.

From swordfights in bamboo groves and ambushes in alleys to crimes of passion and politics, the action comes suddenly, cutting through the delicacy of Japanese relations. In these scenes you can see the influence of the drama of detective fiction and Ikenami’s passion for theatre and his experience as a playwright. The influence of acclaimed filmmaker, Akira Kurosawa, known for his period samurai films in the 1950s and 1960s that popularised the genre, including Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957) and Yojimbo (1961), cannot be overstated.

Although it’s the first book in a long-running series, the story leaves a sense of incompleteness, where solving the crime doesn’t necessarily bring full resolution. In this is not only the social part of the mystery genre, but also the Japanese appreciation of impermanence and incompletion. What we are left with is the understanding of how important social relations are, which trump even justice.

Navigating uncertain waters of morality in a changing world of divided loyalties and motivations, bushido and honour are the only guides on which the samurai can depend – whatever the interpretation. More than just a swashbuckling adventure through Edo, The Samurai Detectives is an important contribution to the detective genre, using the beauty of its world and the struggles of its characters to offer insight into Japan itself.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

AloJapan.com