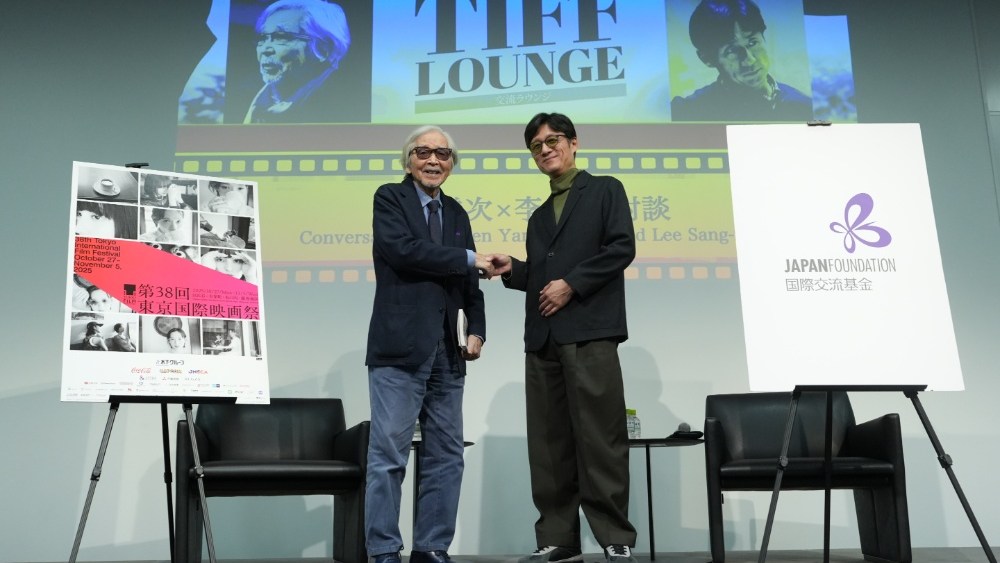

The Tokyo International Film Festival‘s TIFF Lounge series of talks and masterclasses featured a conversation between Yamada Yoji, director of the festival Centerpiece “Tokyo Taxi”, and Lee Sang-il, recipient of this year’s Kurosawa Akira Award for his film “Kokuho.”

The 94-year-old Yamada, whose, lengthy filmography includes the iconic 48-episode “Tora-san” series that ran from 1969 to 1995, and the 51-year-old Lee, whose “Kokuho” has become a record-setting hit since its release in June of this year, earning more than $100 million, expressed admiration for each other’s work. Lee called Yamada a “national treasure” (the English translation of “Kokuho”) while Yamada said that putting his modestly budgeted “Tokyo Taxi” next to Lee’s lavishly staged Kabuki drama “makes me feel embarrassed” and that he was there to “watch and learn.”

Noting that “Kokuho” is the “story of two men” who become performers of female roles or onnagata in Kabuki, Yamada said Lee’s film “is exceptionally good precisely because it’s different from typical films about male friendship” since the focus remains on the two protagonists and their suffering for their art, as well as on their intense rivalry as artists. “Usually in a film like that a woman always gets involved between [the two men] so you have a simple relationship dynamic,” Yamada said. “This movie isn’t like that… I was amazed you managed to express something so complex so well.”

Yamada compared the film to the 1984 Mozart biopic “Amadeus” in which “there was jealousy [between the two protagonists], sabotaging each other and deceiving each other.” In “Kokuho,” he added, “You’d expect that kind of thing to unfold, but, there’s an ‘art’ at the center of the drama. Above all, they dedicate themselves to their art.” He also expressed amazement at how the two leads totally inhabited their female stage roles. “How did they pull it off?” he asked.

Lee answered that stars Ryo Yoshizawa and Ryusei Yokohama spent a year and half preparing, learning Kabuki from scratch. “Honestly, for the first few months, I’d occasionally go observe them, and it would give me a headache,” Lee said. “I’d wonder if they’d ever get it… But that rehearsal process, where they pushed each other to improve, directly shaped the relationship between their characters.”

The two directors also discussed veteran dancer and actor Tanaka Min, who appears as an elderly Kabuki onnagata in “Kokuho” and as a sword-wielding opponent to the samurai hero in Yamada’s 2002 Oscar-nominated hit “The Twilight Samurai.”

“He had a good face and a good voice,” Yamada said. “But his acting… He was just terrible, really terrible. We rehearsed everything, every single thing. And it just didn’t work. So we had to drill in [the dialogue], word by word.”

Noting that Tanaka became an in-demand actor after the film’s success, Yamada said, to audience laughter “I watch him sometimes, and he hasn’t improved at all. ”

Lee countered that Tanaka had a dancerly presence that fit the role: “It’s enough just for him to be there, you know? That presence and the way his body moves. He has this unique way of moving his body, and when that combines with his voice, it creates this magical presence.”

The conversation turned to “Tokyo Taxi,” Yamada’s remake of the 2022 French-Belgian drama “Driving Madeleine.” Frequent Yamada collaborator Baisho Chieko plays an elderly woman who asks her taxi driver (former pop star Kimura Takuya) to drive her to memorable places in her Tokyo life before arriving at the Yokohama retirement home where she intends to spend her remaining days.

Yamada commented that Kimura, who had starred in his 2006 samurai drama “Love and Honor,” was just as serious as a taxi driver stirring natto (fermented soy beans) into his breakfast rice, as he had been as a samurai in the earlier film. “He’s like, ‘I have to do this properly, seriously. That’s who I am,’” said Yamada. “And even when his own scene is over, he always stays until the end, on the set…Big stars usually show up late or don’t care [about staying to the end], but he never does that.”

Lee said that when he visited Yamada’s set the director was “always right next to the camera, always watching the actors from the closest spot.” “I tried it myself, kind of half-jokingly” he added. “I realized how much it matters – having the director right there is incredibly important. That lesson has stayed with me ever since.” Younger directors, he noted, tend to watch a monitor positioned some distance from the camera. “I can’t quite accept that,” he said “If I were an actor, I’d hate it.”

In the Q&A the directors were asked for their thoughts about the enormous global popularity of Japanese animation, as compared to the relatively low international profile of Japanese live-action films.

Yamada admitted that the profits of Japanese anime are “huge” while those of Japanese films “are practically negligible by comparison.” “That’s incredibly frustrating and sad for us Japanese artists,” he said. “Seventy years ago, when I started going to movie theaters, Japanese films were incredibly vibrant and the cinema scene was rich… We have to do something. It’s not just up to us; the Japanese government must seriously take notice of this too. It’s a national issue. Why is Korean cinema demonstrating such incredible power? Because Korea is genuinely committed to making films, truly responding to cinema. That’s why I hope Japan, as a national policy, will support film. I hope that kind of initiative can emerge from Tokyo.”

AloJapan.com