In recent years, news reports and social media have been saturated with stories of global tragedy — from the Russian-Ukrainian war to the conflict in Israel and Gaza — leaving many of us in disbelief at how the world seems to be moving backward.

For refugees fleeing these war-torn homelands, the journey to safety is often met with hostility and suspicion in unfamiliar countries, simply because of their customs and beliefs. Stripped of their homes, friends, and families, these new immigrants often find that the only thing they truly own is their name.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

My name is Julie Keiko Murakami and it is a blend of history and faith. I am a third-generation (“nissei” in Japanese) Canadian of Japanese heritage living in a beautiful west-coast town in British Columbia.

My grandfather, Yoshio, told me that our family name, Murakami, means “village on the mountain” in Japanese. He said our ancestors were devout, celibate priests caring for ancient Japanese shrines in these mountain forests. He would laughingly point out that we obviously descended from naughty monks, otherwise we wouldn’t be here today. As a young man, he immigrated from Wakayama, Japan, to Canada in 1927. He worked in various logging camps across British Columbia as a lumberjack, specializing as a tree topper — a dangerous but well-paying job. When he had finally saved enough money, he sent for his wife and three-year-old son, my father, to join him in Vancouver. My grandmother was delighted to see that my grandfather had saved enough money to buy a car, a cozy one-bedroom house overlooking the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) fairgrounds, and even a new washing machine. She quickly found work as a seamstress and eventually gained recognition as the official dressmaker for the Vancouver Miss Chinatown pageant.

In early 1942, everything changed. Their new life was upended as World War II escalated. My grandparents, now labelled “enemy aliens” despite being Canadian citizens, were forcibly removed from their home and sent to live in the horse stalls inside the Agrodome building at the PNE — the very place they once admired from their little house. Betrayed by a country they had pledged their loyalty to, they lost their house, car, jobs and dignity. Each person was allowed only one suitcase of personal items.

My grandfather tried to make light of this painful time and told me that, of all their possessions, my grandma cried the most over the loss of her new washing machine. He was sent to a work camp building roads in B.C.’s interior and my grandmother was left at the PNE livestock building with two children under the age of five. Despite efforts to scrub down the stalls, the lingering smell of animals and manure was overwhelming and the unsanitary conditions led to illnesses. My exhausted grandmother was kept busy chasing my mischievous father, who loved to play hide and seek through the maze of cattle stall aisles.

More on Broadview:

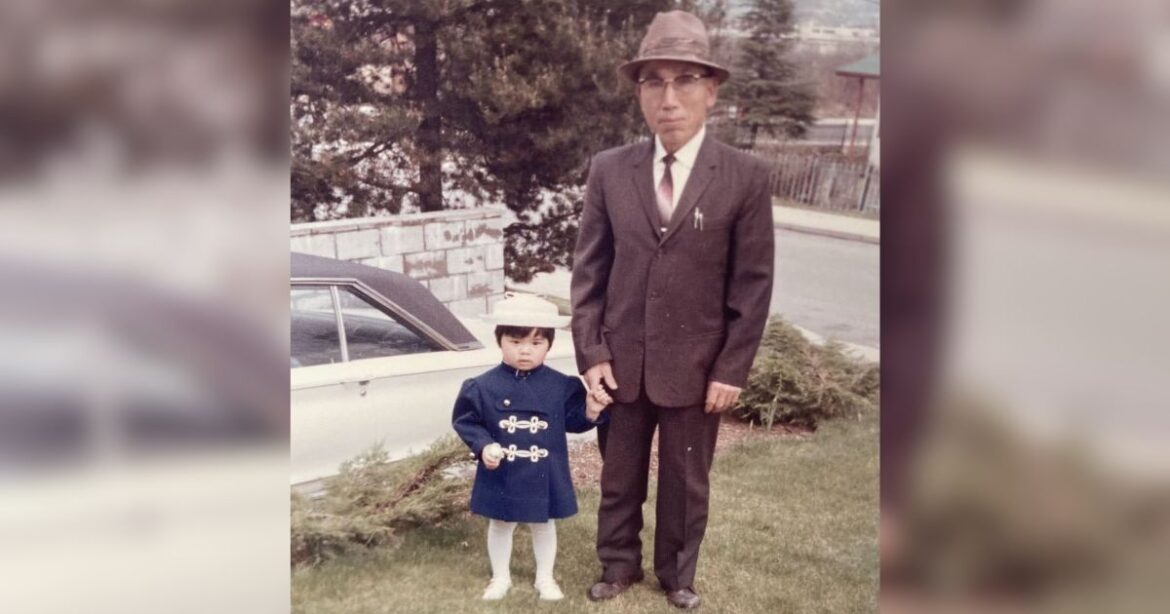

They never could have predicted that 25 years later, they would be returning to the PNE fairgrounds — not as incarcerated enemy aliens, but as ordinary grandparents taking their first grandchild to the amusement park. As a child, I loved seeing the farm animals in the Agrodome building and never understood why my grandparents were so reluctant to go inside. It wasn’t until years later that I realized just how strong their love for me was — that they would be willing to relive painful memories just to indulge their first grandchild’s wish to see the “piggies.”

During the war, my grandfather and grandmother were eventually reunited and relocated to an internment camp east of Hope, now known as Sunshine Valley. Two or three families had to share unheated shack-like buildings, endure endless lineups for food, clothing and access to the bathroom or shower. They became very resourceful at recycling and foraging in the woods to supplement their meagre diet.

The most troubling challenge, however, was the loss of spirit and hope. Fortunately, Rev. W. R. McWilliams, a former United Church missionary to Japan who was fluent in Japanese, came into their lives. He had returned to Canada in 1939 and was ministering at Japanese United Church in New Westminster. He and his church members advocated for better living conditions for internees and most notably, provided high school education for the older children by calling on other missionaries who had worked in Japan before the war. He also organized activities and tried to enlighten the nearby townspeople who looked upon the Japanese-Canadian citizens as dangerous enemies. Weary and angry at the world, my grandfather was distrustful of this man who represented a religion that he found foreign and different from his traditional Shinto upbringing. My grandmother told me there were many nights when McWilliams and my grandfather would stubbornly debate Christianity over cups of hot green tea. What kind of God, my grandfather would argue, would allow people to be treated this way?

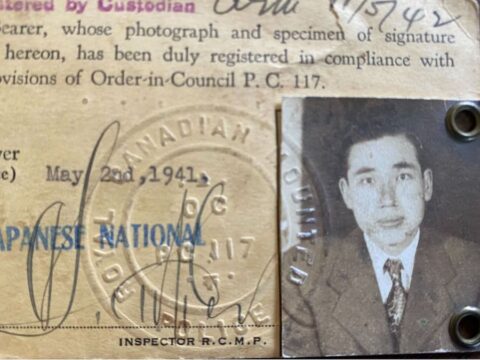

The wartime registration card for Yoshio, Julie Murakami’s grandfather. (Photo provided)

The wartime registration card for Yoshio, Julie Murakami’s grandfather. (Photo provided)

Ultimately, it was McWilliam’s actions and not just his words that inspired my grandfather and many other Japanese-Canadians to join the United Church and be baptized as Christians.

After the war, these former camp internees worked together to keep Vancouver Japanese United Church alive. It continued to be a place for worship, celebration and community growth. When I was born, I was named Julie in honour of Julie Andrews, my family’s favourite singer, with the hope that I would also be good at music. (I was and made a career out of it!) I also grew up in this church — was baptized here, attended and later taught Sunday school, and many years later, I even got married there.

One day, as my family was sitting around the table sipping cups of green tea after a family dinner, I asked my grandfather why he had chosen “Keiko” as my Japanese middle name.

“Ah Ju-ree-san,” he said (With his Japanese accent, he can’t pronounce “L’s”), “It is a ru-vely (lovely) name. It means “breast.”

I was horrified. Clutching my chest, I yelled, “what!! My name means breast?”

“Yes, Ju-ree-san,” my grandfather said solemnly, gazing upwards and holding his hands to the heavens, “You are breast …breast (blessed) by God.”

My family is deeply indebted to the United Church for giving them hope in a time of crisis and for nurturing a quiet faith that has shaped my life — and even my name.

***

Julie Murakami has a B.Mus in piano and is a retired elementary school music teacher living in B.C.

AloJapan.com