Given the islands’ split personality, a visit can induce whiplash: One moment you’re under palm trees listening to the delicate plucking of sanshin string music, the next you’re driving through a stretch of shops and fast-food joints more nostalgically American than most corners of the U.S.

On a recent trip, I realized that this complexity, even dissonance, makes Okinawa one of the most fascinating and unusual places to visit in Japan right now. Bonus: Few Americans and Europeans go, so it feels much less congested than hot spots like Kyoto.

On this visit, my fourth, I focused on Okinawa Honto, Okinawa’s largest island, a three-hour flight from Tokyo and home to great beaches and to Naha, the capital city. When I first encountered Naha, 20 years ago, it felt like a one-street resort town, littered with souvenir shops and steakhouses.

This time, Stephen Lyman, a Japanese spirits expert and importer, steered me away from Kokusai-dori, the tourist strip, and sent me in search of a young Okinawan bartender named Koji Higa.

Following clues picked up from Instagram, I climbed some hills above the town’s main street and wandered through a quiet residential neighborhood, looking for his bar. After clambering up three flights of a dark apartment-building stairwell, I entered Higatei, which celebrates all things awamori, an Okinawan rice-based spirit.

View Full Image

Bar owner Koji Higa prepares an awamori-based cocktail at his bar, Higatei.

Higa greeted me at the door and proceeded to pour me some of his favorite long-aged awamoris. I had read that nearly all awamori distilleries and stockpiles were destroyed in 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa. I asked Higa about the industry’s struggles to recover. “It’s taken 80 years, since the end of the war, for awamori to re-establish its cultural presence,” he said. “The real story begins now.”

The U.S. military occupied Okinawa until 1972 and though the archipelago constitutes only 0.6% of the country’s landmass, it still hosts more than half of all U.S. military personnel in Japan. Curious to see the effect of all that Americanness, I drove north from Naha to Makiminato, a place once dominated by American bases, off-base housing and base-adjacent businesses. Though the military presence has since mostly relocated farther north and behind barbed wire, a bizarre, lingering, nostalgic version of an older America persists there.

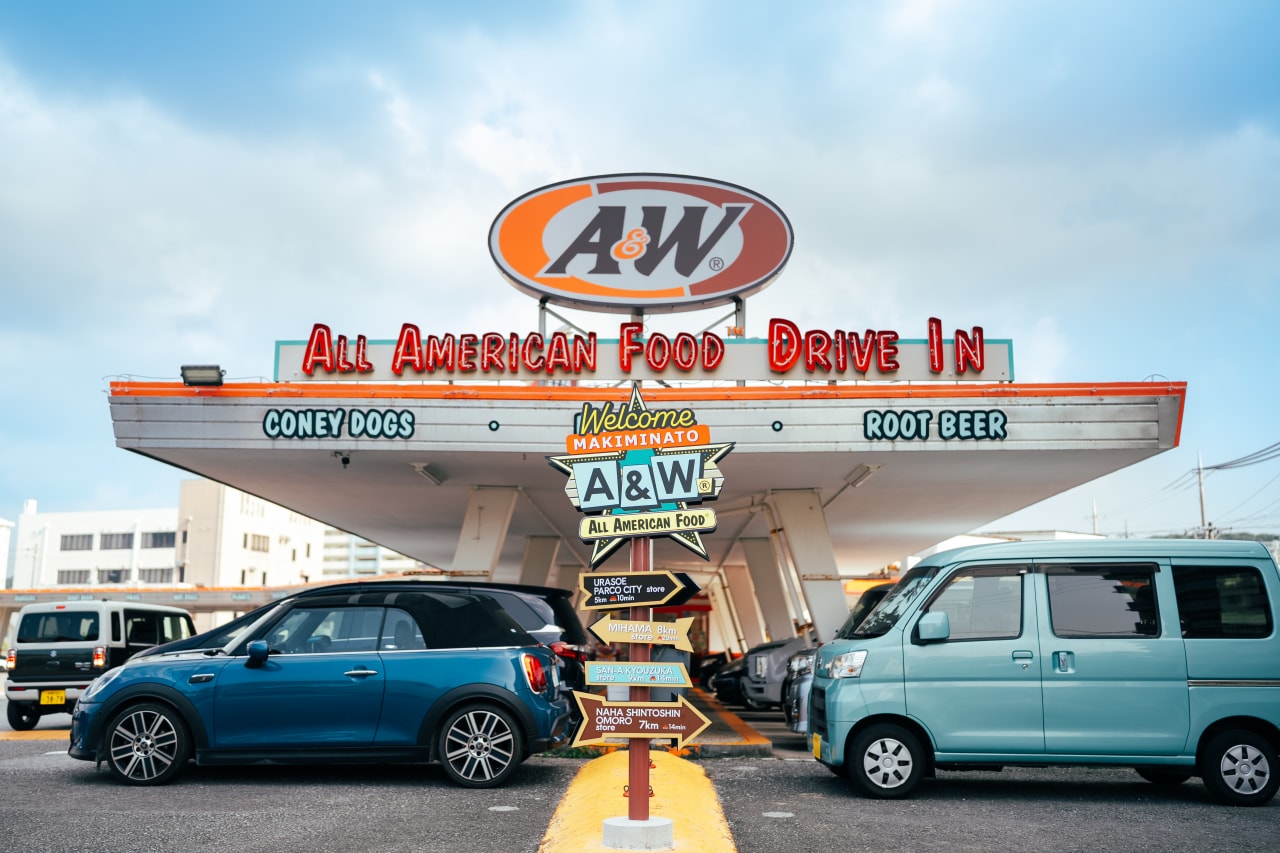

Below a giant mural featuring a white woman in an A&W cap, dozens of visitors from Japan and elsewhere in Asia waited in line outside Makiminato’s A&W Drive-In, which has preserved all of the old-school drive-in infrastructure but now operates like an ordinary fast-food joint. Inside, customers sipped root beer flats and ate cheeseburgers.

View Full Image

A&W Makiminato retains all its original drive-in infrastructure.

Down the road, I found one of the first locations of Blue Seal, a chain of ice cream parlors that was started on a U.S. base in 1948 by an American dairy conglomerate, but lives on independently in Okinawa.

Nearby, I pulled into King Tacos to sample a peculiar hybrid cuisine born out of the long intermingling of American, Japanese and Okinawan culinary traditions. The story goes that in the early 1980s, at a now-closed branch of King Tacos, which catered to American soldiers, chef Matsuzo Gibo created what has become an iconic dish across Japan: Okinawan taco rice, consisting of minced beef and other taco toppings, liberally seasoned, served atop a bed of Japanese white rice. The crunch of the iceberg lettuce and the familiar taste of sliced American cheese reminded me of the Old El Paso brand taco kits my mom used to serve in the ’80s—about 7,000 miles away.

Most visitors to Okinawa arrive at the resort-lined Motobu Peninsula in the north and never leave. I took one look at the giant, corporate beach resorts and kept moving. I followed a small road into the tree-covered village of Bise, where I found B&B Pastoral. The owners, who also run a book and crafts shop, escorted me to my room in an annex made of wood, with clean lines that converged on large windows. The room smelled strongly of cedar, which came from an oval soaking tub at the center of the bathroom.

That afternoon, I visited Yamakawa Shuzo Distillery where I saw the awamori renaissance in action. The distillery’s third-generation owner, Munekuni Yamakawa, explained his mission: to age his awamori as long as possible in the hopes of re-creating the taste of the awamori that had been lost after World War II.

The next morning, after a soak in the cedar tub, I ventured out for breakfast at Tida Moon, a restaurant recommended by Higa, the bar owner in Naha. The tray that emerged from the kitchen was a highlight reel of Okinawan cuisine, prepared by Fumiaki Takada, a Tokyo chef versed in French, Italian and Japanese cooking. Thin slivers of pig’s ears came with long-cooked pork belly. In one corner, sautéed bitter gourd—in another, briny sea grapes.

“For years we’ve been coming here to Okinawa,” said Takada, referencing his partner, who helps run the restaurant. “But last year we finally decided to open this restaurant. I found someone to teach me Okinawan home cooking and that’s what we serve for breakfast. We are obsessed with Okinawa and its culture and cuisine.”

View Full Image

A breakfast spread at Tida Moon, which specializes in Okinawan cuisine as interpreted by a Tokyo chef.

Later that day, I walked down Bise’s tree-lined streets until I reached a rocky shore, where locals gathered outside a tiny all-purpose grocery store. Nearby, tourists watched the sunset. I waded into the crystal-clear water, and felt a strong current pull me.

At first I swam against it, trying to return to my entry point. Then, seeing that the current flowed toward a safe, if undefined, point along shore, I stopped fighting and let it take me where it would.

AloJapan.com