People whose surname starts with an A, I, U, E, O vowel, the first row in Japanese syllabary, are blessed with a head start in life, a study suggests.

It found that individuals in this category statistically stand out, making it easier for them to scale the career ladder.

Surnames like Aoki, Aida or Inoue could spark envy in some people whose last name verges on pedestrian, according to a research paper published in June in the Japanese Economic Review, the journal of the Japanese Economic Association.

Eiji Yamamura, a professor at Seinan Gakuin University in Fukuoka who specializes in behavioral economics, said studies in Western countries have shown that people with surnames starting with letters early in the alphabet seem to have a built-in advantage.

For example, when recommending or selecting someone from a list, people tend to choose names that are more likely to catch attention, rather than carefully comparing each individual’s abilities and achievements, he said.

But does the same apply in Japan?

Yamamura and a colleague gathered the names of so-called elite individuals who gained prominence in a wide range of fields after World War II.

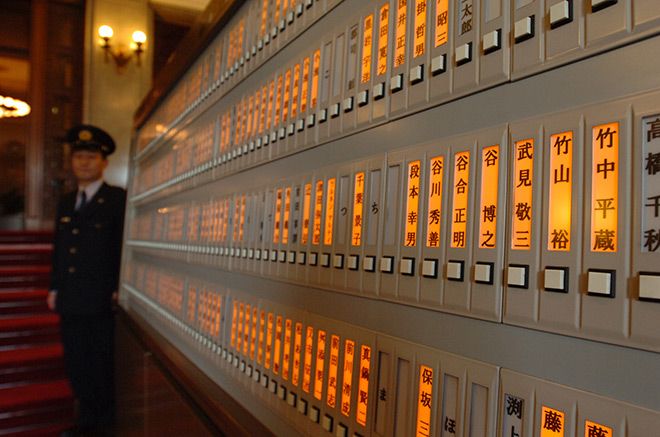

These included members of the Japan Academy, considered the highest body in academia; Nobel Prize winners; presidents of various academic societies; former prime ministers; vice ministers of government ministries; prefectural governors; Supreme Court justices; University of Tokyo professors; and executives of Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) and Keizai Doyukai (Japan Association of Corporate Executives).

Even after they limited the list to men, whose surnames are less likely to change due to marriage, it still totaled around 2,000 individuals.

They found that surnames starting with the “A” row–A, I, U, E or O–the first row in Japanese syllabary, accounted for about 22 percent of the Japanese population, but made up roughly 27 percent of the elite group, a statistically significant difference.

In contrast, surnames starting from the “K” row, the second in Japanese syllabary, and those from the subsequent rows, appeared in proportions similar to or lower than their representation in the general population.

On the other hand, among those who passed the University of Tokyo’s tough entrance exam or took the Mathematical Olympiad, surnames starting with the “A” row were not particularly prevalent.

This suggests that a surname starts to exert influence after a person graduates from school and begins focusing on a career.

The custom of listing names in syllabary order is said to have begun to spread in Japanese society between the Taisho Period (1912-1926) and early Showa Period (1926–1989).

What was it like before then?

Yamamura and his colleague examined the names of 1,455 individuals who passed a government exam to gain high-status jobs in the bureaucracy between the Meiji Period (1868–1912) and early Taisho Period.

They found no significant difference in the proportion of “A” row surnames compared with the general population. Nor was there a higher proportion of “A” row surnames among those from Shizoku, a relatively higher social class of former samurai warrior families.

Yamamura concluded that the overrepresentation of “A” row surnames among the elite is due to the practice of listing names in Japanese syllabary order, not because social status was inherited from parents or earlier generations.

He speculated that people with “A” row surnames are more likely to be called on by teachers in school, giving them more opportunities to act as role models and gain life experience. These accumulated experiences may contribute to later social success.

“Those who go first have no one to imitate, which may foster creativity,” Yamamura said. “To eliminate unequal educational opportunities, we should adopt systems that select people randomly, regardless of their names.”

He went on: “I have a surname starting with the ‘Ya’ row, so I was always called on last in elementary school. It’s something I’ve always been conscious of.”

The paper can be read online at (https://doi.org/10.1007/s42973-025-00219-3)

AloJapan.com