To begin this conversation, I’d like to talk about the role of Japan’s regional areas. With ongoing demographic decline and seismic risks, regional revitalization is increasingly important. Could you share your thoughts on the significance of revitalizing local economies and decentralizing from Tokyo in the context of Japan’s future economic growth?

Certainly. I was born and raised in Shibuya, the heart of Tokyo, and my family has lived in the city for generations. Yet I made the decision to leave Tokyo and become the Governor of Kumamoto. In a way, I see myself as a symbol of decentralization. The broader challenge Japan faces is a national population decline, not just regional shrinkage. Urban concentration in Tokyo exacerbates this, but ultimately, it’s the country as a whole that’s aging and shrinking. The root of this is declining birthrates—fewer children are being born every year.

If we want to reverse this trend, we must acknowledge that raising children in Tokyo is increasingly difficult due to congestion, high living costs, and limited space. Regional areas like Kumamoto can offer families a better quality of life—more space, more affordability, and a community conducive to raising children. I believe this shift is essential to building a more child-friendly Japan. As for why so many people continue to move to Tokyo, I think it’s partly cultural. Japanese people tend to prefer being in groups, and Tokyo is seen as the center of opportunity. There’s also a hesitancy to go abroad, partly due to language barriers. This further funnels ambition and mobility into Tokyo. But Kumamoto is actively challenging this trend. We want people to realize that you can take on meaningful challenges here without needing to be in Tokyo. Whether you’re from Tokyo or overseas, you can pursue innovation, business, and creativity in Kumamoto. Our goal is to make Kumamoto as attractive and competitive as Japan’s capital—not just a backup option.

Let’s talk about education. With TSMC entering Kumamoto, we understand there’s been a push to internationalize local education. Could you explain what steps Kumamoto has taken to accommodate global talent, especially for the children of foreign professionals?

That’s a very timely point. When TSMC decided to invest in Kumamoto, one of the biggest challenges wasn’t infrastructure or logistics—it was education. Specifically, how to provide an international-standard education for the children of employees coming from Taiwan and elsewhere. We responded by creating English-language classes at Kumamoto University-affiliated elementary and junior high schools. We also expanded existing international schools and enhanced their facilities.

This has had a profound impact on our region. Japan has traditionally lagged behind in English-language education. The arrival of TSMC was like a black ship—it brought a level of disruption and innovation that triggered a revolution in our educational environment. We are now seeing tangible changes: expanded curricula, new programs, and a growing openness to international students and educators. We’ve invested heavily to build an ecosystem that supports international education, not just for foreign families but for Japanese students as well.

Japan experienced an economic peak during the bubble era of the 1980s and early 1990s. But since then, it has struggled with stagnation. How do you see the importance of opening up to the world in reversing this trend?

After the postwar boom that lasted roughly until 1990, Japan entered a long period of stagnation—deflation, shrinking demand, and declining competitiveness. One of the reasons, in my view, is that Japan did not open up enough to the world. We didn’t aggressively pursue global markets or embrace foreign talent and ideas. As a result, we fell behind in international competition. To survive and thrive, Japan must now earn foreign demand—bring in international investment and export more value-added products and services. And we must welcome more people from overseas into our society. Otherwise, with a shrinking domestic population, our internal demand will continue to decline, and Japan’s economy will suffer. But I’m optimistic. Japan remains a country that is seen as safe, clean, and fascinating by visitors. In global tourism surveys, Japan consistently ranks among the top destinations people want to return to. We must leverage that brand value while building deeper, long-term connections with the world.

Kumamoto’s location makes it especially interesting—it’s far from Tokyo, but well-positioned within East Asia. How does this geographical reality play into your long-term vision?

While Tokyo and Kumamoto are about 1,000 kilometers apart, Kumamoto is just as close to Shanghai and Taipei. This gives us a unique geopolitical advantage. Rather than seeing ourselves as Japan’s periphery, we see ourselves as East Asia’s center. That perspective transforms Kumamoto from a remote outpost into a strategic hub for trade, logistics, and innovation. This regional strength, when fully utilized, becomes a powerful growth engine. It’s one of the keys to Kumamoto’s future and to Japan’s broader revitalization.

Kusasenri, a vast grassland located on Mount Aso in Kumamoto Prefecture

The food culture is also one of its attractions, and you can enjoy not only horse sashimi but also a wide variety of alcoholic beverages such as sake, shochu, whiskey, wine, and craft gin.

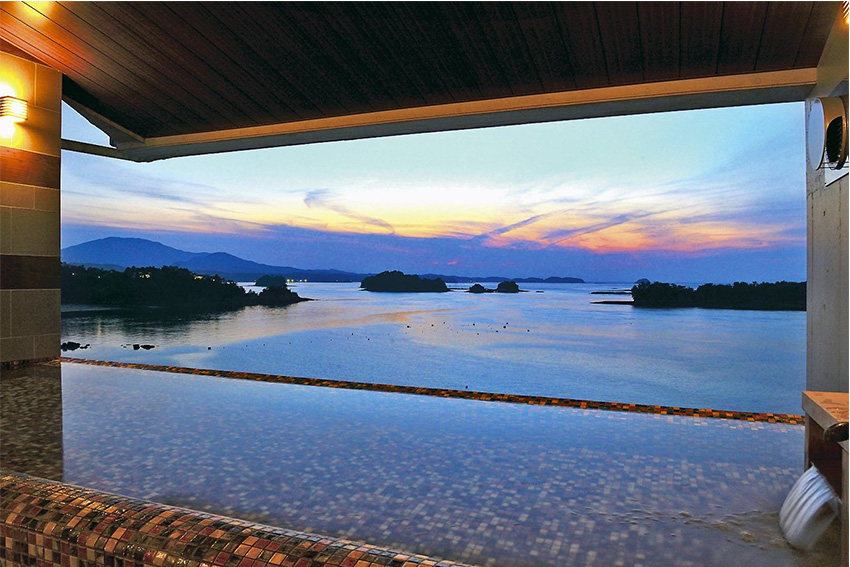

There are also many hot spring resorts, and the prefecture has a variety of tourist attractions that are world-class.

Previous Next

With the return of the semiconductor industry to Japan—particularly TSMC’s presence in Kumamoto—how do you view this industrial renaissance? And how do you avoid repeating past mistakes?

This is a crucial point. Back in the 1980s, Japan led the world in semiconductors. Companies like Toshiba and Hitachi were global giants. But eventually, the industry declined. We focused too much on producing high-quality chips, and not enough on developing downstream industries that could harness those chips in innovative ways. Labor costs pushed production overseas, and Japan lost its edge.

This time, we need to do things differently. Producing quality chips is important, but it’s not enough. We must foster industries that use these chips—AI, robotics, autonomous vehicles, and more. That’s where the real value lies. In Kumamoto, we’re working to create that innovation ecosystem. We’re encouraging collaboration between universities and industry—what we call “industry-academia partnerships.” Our model is Silicon Valley or Taiwan’s science parks. Government alone can’t drive innovation. It has to be led by companies and universities working together. Kumamoto offers the space, natural beauty, and creative environment where such collaboration can thrive.

In fact, some IT firms from Tokyo’s Shibuya district have already relocated their innovation teams to the Kumamoto coast. They say ideas emerge more freely here, where they can work while looking out over the sea. That kind of environment nurtures big thinking.

What role can international entrepreneurs play in Kumamoto’s innovation ecosystem?

It’s a critical role. Japan still has many regulatory barriers that make it difficult for foreign businesses to operate here. What worked well with TSMC was the formation of a joint venture—JASM—with Sony, Toyota, and Denso. This type of partnership, combining foreign capital with strong domestic players, is a model we need to expand. On the academic front, Kumamoto University has signed MOUs with top Taiwanese universities. Tokyo University has even set up a satellite semiconductor research center on the Kumamoto campus. These alliances are beginning to produce world-class research and collaboration, with companies like TSMC and Sony providing not just funding but personnel. This is exactly the kind of structure we need to replicate.

Lastly, let’s talk about tourism. Kumamoto seems to have great potential, especially with its proximity to Taiwan and China. What are some of your region’s key attractions?

Kumamoto is blessed with natural beauty. Mount Aso, for example, is home to one of the world’s largest volcanic calderas and is a candidate for UNESCO World Heritage status. On the coast, the Amakusa islands offer stunning seascapes and marine life. We have world-class hot springs as well. The local cuisine is also exceptional—famous for horse meat sashimi (basashi), and a wide range of spirits including sake, shochu, whiskey, wine, beer, and craft gin.

One challenge is that travelers from nearby regions like Taiwan and China often stay for only a few days. We’re working to attract longer stays and eventually expand our appeal to European and North American visitors. But for now, our proximity to Asia gives us a competitive edge, and we plan to make the most of it.

If you continue your term as governor for another 10 years, what would you like Kumamoto to look like by then?

Realistically, we can’t reverse population decline overnight. Even if birthrates rise next year, it will take at least 20 years for the next generation to start having children. What we can do is slow the pace of decline and design our communities accordingly.That’s why we’re pursuing the idea of a “compact city”—encouraging people from remote areas to relocate closer to the urban core, so we can maintain quality services and a strong sense of community even with fewer people. We’re also modernizing agriculture by focusing on high-value crops, such as organic produce that can be sold directly to consumers in Tokyo or overseas. Instead of just shipping raw tomatoes, we can process them into frozen products here and export them. That way, the added value stays in Kumamoto.

Thank you very much.

For more information, please visit their website at: https://www.pref.kumamoto.jp.e.qp.hp.transer.com/

AloJapan.com