The author, Raymond Woo, is the Singapore Office Representative of Kyoto iCAP (Kyoto University Innovation Capital), the venture capital arm of Kyoto University. He was previously with Temasek-funded Pavilion Capital and has over 15 years of experience in investment, financial advisory and policy in Japan and Asia.

Over the past month, Japan was in celebration when Professor Shimon Sakaguchi of the University of Osaka (and formerly from Kyoto University) won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and Professor Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

While they were Japan’s 30th and 31st Nobel laureates respectively, what is unprecedented is that both are involved in deeptech university spinoffs — Professor Sakaguchi is the scientific founder of immunotherapy startup RegCell (a Kyoto University Innovation Capital, or Kyoto iCAP, portfolio company), while Professor Kitagawa is advisor to advanced materials startup Atomis.

For the first time, Japan’s Nobel-winning scientists are not only pushing the boundaries of knowledge but also stepping directly into entrepreneurship. It is a signal that the golden age of university tech commercialisation has arrived in Japan.

For the first time, Japan’s Nobel-winning scientists are stepping directly into entrepreneurship.

From research excellence to market relevance

Japan has long been a scientific powerhouse. The country consistently ranks among the global top five in publications and patents in physics, chemistry, and materials science, and it spends 3.4% of GDP on R&D, comparable to the United States, and significantly higher than most other Asian countries including China and Singapore. Kyoto University alone has produced 11 Nobel laureates, the most in Asia.

Yet historically, Japan struggled to turn that intellectual capital into commercial impact. While its researchers generate world-class breakthroughs, the ecosystem to translate them into globally competitive companies has lagged. The reasons are structural and cultural: a conservative financial sector, low risk tolerance, and an inward-looking research environment.

Professors at top US research universities such as Stanford and MIT routinely spin off startups that attract private capital and global talent. In Japan, the gulf between the laboratory and the marketplace has, until recently, been vast.

That gap is now closing—rapidly.

The decade that changed Japan’s innovation landscape

Around 2013-14, Japan began planting the seeds of its deeptech revolution. Recognising that world-class research was being lost in the “valley of death” between discovery and commercialisation, the government and leading universities poured billions of yen into institutional reforms and early-stage support.

University technology transfer offices (TTOs) and venture funds were established across the country. Kyoto University, a public university, was among the pioneers, creating Kyoto iCAP in 2014 as its dedicated venture arm to commercialise university-born research and technology.

Since then, the transformation has been striking. iCAP has built a portfolio spanning regenerative medicine, quantum computing, and advanced materials. Despite its focus on early-stage deeptech — the hardest segment in venture capital — iCAP has achieved six to seven exits through IPOs and M&As, with several companies on track to reach unicorn status.

Crucially, over 70% of iCAP’s portfolio is co-invested with private VCs, demonstrating that government-linked venture capital can crowd in, not crowd out, private money. This is due to its nature as a patient and risk capital provider to and incubator of early-stage deeptech startups, because of public funding and its very long fund life of 12-15 years plus five-year extension.

Other universities followed suit. Today, 85% of Japan’s top universities have venture funds, up from fewer than half a decade ago. The University of Tokyo Innovation Platform (UTokyo IPC) manages over $400 million, while Osaka and Tohoku Universities have launched VC funds in the hundreds of millions.

Government as a catalyst for deeptech

A key accelerant of this ecosystem is the University Fund of Japan (UFJ) — a 10 trillion yen ($67 billion) endowment established in 2022 by the Japanese government to support research excellence and commercialisation. It can provide up to 300 billion yen annually for up to 25 years, giving universities and their venture arms the long-term capital horizon deeptech requires.

Japanese university spinoffs are scaling faster than ever before

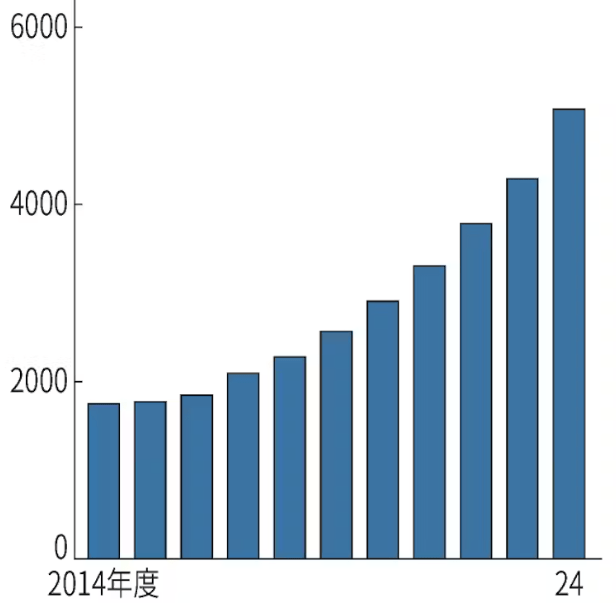

These efforts are finally bearing fruit. Japanese university spinoffs are scaling faster than ever before. According to METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), the number of university spinoffs in FY2024 rose by 18% (additional 786 startups) to 5,074 startups, the highest by both growth and total number to date, and more than twice higher than the less than 2,000 startups in FY2014.

Number of university spinoffs in Japan

Source: METI.

Source: METI.

Kyoto, Osaka, and Tsukuba are emerging as vibrant innovation clusters, drawing international investors who previously overlooked Japan.

In recent years, global VC firms like Eurazeo, Vertex Ventures, and Alumni Ventures have set up Tokyo offices or Japan-focused funds, joining established domestic players such as Global Brain, UTEC and Incubate Fund.

In other words, Japan, long known for producing knowledge, is learning how to capitalise on it.

The missing piece: global bridges

Despite these achievements, Japan’s innovation engine still runs below its potential. The challenge is no longer invention, but (global) connection.

Japan remains relatively insular. Its deeptech startups are often founded by brilliant scientists who have limited global exposure or access to international markets. The scarcity of foreign researchers and entrepreneurs who could have functioned as bridges between Japan and the outside world—a fraction of the number found in comparable Western ecosystems—limits Japan’s ability to build truly global companies.

Out of more than 910,000 researchers in Japan as of 2022, less than 13,000 of them or 1.4% were foreign nationals, and the number has not risen since 2000! In contrast, 19% of all STEM workers and 43% of doctorate-level scientists and engineers in the United States are foreigners.

In the United States, since 2000, more than 40% of US-based Nobel laureates are foreign-born (including three out of six US Nobel laureates in 2025), and cross-pollination between academia and industry is ingrained.

Furthermore, Singapore, South Korea, and China have deliberately globalised their innovation ecosystems. Singapore’s Startup SG Equity programme co-invests up to S$ 12 million per startup and recruits international founders. China combines massive state funding with global collaboration, allocating 1.3 trillion yuan ($190 billion) in R&D tax rebates in 2022 and launching a 1 trillion-yuan ($138 billion) venture fund for emerging technologies in 2025.

Japan’s unique advantage lies in its scientific depth, and indeed its fundamental research capability surpasses other Asian countries despite the latter’s relatively better developed VC and startup ecosystems. However, it must become more open to people, to ideas, and to global partnerships.

Imagine if Japan could attract even a fraction of the world’s scientific talent currently constrained by tighter immigration policies and rising populist nationalism in the US and Europe. With the right visa programmes, research partnerships, and startup and research support, Japan could become the magnet for global deeptech talent in Asia.

A New Era: From ‘Japanese’ to ‘Global’, from Japan

Compared to ten years ago, Japan’s startup landscape is unrecognisable. Valuations are rising, more researchers are becoming founders, and the number of university spinoffs is growing at double-digit rates. The government’s Five-Year Startup Development Plan targets 100,000 startups and 100 unicorns by the early 2030s, a goal that would have seemed unimaginable a decade ago.

Japan’s Five-Year Startup Development Plan targets 100,000 startups and 100 unicorns by the early 2030s.

The momentum is real. But to turn this progress into a sustained revolution, Japan must be unequivocal and aggressive in attracting top scientific and commercial talents to Japan and building bridges globally and decisively embrace openness. It must send a clear message that the era of “closed innovation” is over. Japan should be unequivocal and aggressive in attracting top talents to Japan and building bridges globally.

The combination of world-class research, patient capital, and growing investor confidence has set the stage. The missing link is global integration – the bridges that connect Japanese innovation with the world.

If Japan succeeds, its next generation of Nobel Prizes and deeptech unicorns will not just be “Japanese”. They will be “global, from Japan”, proof that the country’s long-awaited deeptech revolution has arrived, and with it, the golden age of university tech commercialisation.

AloJapan.com