October 15, 2025

TOKYO – Where does all the animal dung go, and how does the zoo deal with it?

That question came to my mind recently when I visited a zoo in the city of Hamura, western Tokyo, to cover an event.

To answer that question, Masakazu Isobe, the management officer of Hamura Zoo, took me to a service center right near the entrance. On a shelf, among souvenirs and beverages, bags of what looked like soil had been placed.

Printed on them alongside illustrations of giraffes and monkeys were the words, “Earth-friendly compost in line with SDGs” (U.N. Sustainable Development Goals).

“This compost is made from animal droppings and straw used for animal bedding,” Isobe, 39, explained proudly.

About 23 tons of dung and used straw are generated annually at the zoo, which is also known as Hinotonton Zoo. According to Isobe, some of the compost produced on site is used to grow grass to feed the animals, while the rest is sold.

Each seven-kilogram bag of compost sells for ¥300. The compost is also sold at the city’s farmers’ market. In 2024, about 2,100 bags were sold, bringing the zoo a profit of roughly ¥530,000.

The zoo also provides farmers with “semi-finished” compost, which hasn’t fully decomposed, free of charge. Including this, the total annual amount of compost distributed outside the zoo exceeds 22 tons.

Collected droppings and straw are placed on the left side of the composting facility, and the mixer moves them inside the machine. PHOTO: THE YOMIURI SHIMBUN

The compost is produced in a 3.5-meter-high, 5-meter-wide, 15-meter-long shed in a yard in the zoo. Zookeepers collect droppings from each facility they are in charge of and bring it to the shed by bicycle or other means once a day. The equipment has concrete wall and a large mixer and is oval-shaped like a racetrack.

The mixer slowly rotates, causing the droppings and other materials added by keepers to ferment. About two weeks later the compost is ready. It is sifted to remove stones and other debris and then bagged.

The composting facility was created one year before the town became a city in 1991. Prior to that, droppings had been disposed of weekly by waste management companies, costing about ¥930,000 annually, according to the city’s civil engineering division.

Leftover straw and fallen leaves used to be piled up in the zoo and left to rot, which prompted the decision to introduce the composting system. At the time, similar composting machines had been installed at only three locations in Japan, including a poultry farm in Chiba Prefecture. The Hamura Zoo was the first zoo in the nation to introduce a facility dedicated to the practice.

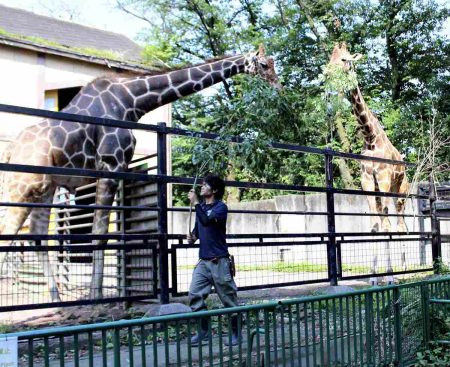

Leaves eaten by a giraffe will be digested and become droppings. PHOTO: THE YOMIURI SHIMBUN

The largest amount of the droppings at the zoo are produced by two zebras, followed by two giraffes and six porcupines. “Herbivores that eat a lot of feed produce a lot of droppings,” Isobe notes.

Initially, the compost produced at the zoo was provided free of charge to nearby farmers and gardening enthusiasts. Starting in 1991, distribution was expanded to all municipal residents. In 1998, full-scale commercial sales began after test sales.

However, the road to commercialization was not easy. Takehisa Ishida, who joined the zoo in 1995, recalled, “Back then, for some reason, the mixer wouldn’t circulate properly, and we weren’t producing much compost.” Staff members had to modify the system to enable large-scale production.

Ishida, 66, whose parents ran a farm, took over the family business full-time after his retirement. He cultivates open-field vegetables, grapes and kiwifruits. He uses the zoo’s compost too, praising it as “well-fermented, just as its reputation suggests — I can grow excellent vegetables.”

Farmers send vegetables

The Tokyo metropolitan government’s three zoos outsource the disposal of droppings and other waste at their facilities to companies on the condition that they are composted as part of their recycling efforts, according to the Tokyo Zoological Park Society based in Taito Ward, Tokyo. The society manages and operates the zoos and aquariums affiliated with the Tokyo metropolitan government.

In the case of Tama Zoological Park in the city of Hino, the contracted company’s processing plant is in Gunma Prefecture, and the compost is sold to nearby farms and households.

At Maruyama Zoo in Sapporo and Nihondaira Zoo in Shizuoka City, droppings are composted at the zoos in special facilities. The compost is used as fertilizer for the zoos’ lawns and trees or given to local farmers.

As for Hamura Zoo, farmers who receive its compost sometimes send back vegetables, which are fed to the animals. “Compost has created a local-level cycle,” said zoo director Shingo Sato, 52. He emphasized that composting reduces both incineration costs and environmental impact.

When the zoo holds field classes for junior high and high school students, the students learning about the compost cycle, from feed to droppings to compost, and then enthusiastically bag the product.

“I am proud of our zoo’s compost production, which is significant in a variety of ways,” Sato said.

AloJapan.com