Shinjuku Station in Tokyo. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

Congratulations! You’ve been handed the dream business travel assignment. Here’s how to maximize your free time in Japan, whether it’s a matter of hours or a few extra days.

October 9, 2025 at 6:30 AM EDT

In 1946, anthropologist Ruth Benedict published The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. The American government had tapped her as a researcher during World War II to help better understand the people on the far side of the Pacific. Scholars heralded her book as a seminal work of social science, but there was one major issue: Benedict had never visited Japan.

Eighty years later, Japan feels like the epicenter of the rest of the world’s collective vacation ambitions. It’s the tourism industry’s darling destination since the melting of post-pandemic travel restrictions, with a little help from a weaker yen. Visitation numbers have eclipsed statistics from the late 2010s, as with each passing year throngs of smartphone camera-clickers interrupt the calm of Kyoto’s temples or the bliss of pink-hued sakura—or cherry blossom—season. And yet, despite Japan’s omnipresence on social media, it remains a place where visitors are in desperate need of a cultural guide.

Read more: Japan’s Best Countryside Hotels That Easily Slide Into Any Itinerary

You may find it challenging to fully leap over the higher hurdles of language and unfamiliar social protocols. But that doesn’t mean you can’t break away from the well-trodden tourist circuit that prioritizes (fetishizes?) Japan’s cultural totems of extreme oldness and extreme newness.

Featured in the October/November Bloomberg Markets. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

In fact, traveling to Tokyo on business may be the easiest way to tap into a vein of the local and everyday. The world’s largest metropolis is one giant cityscape of commuters on the move. Instead of 400-year-old shrines or built-yesterday multisensory “experience” museums, you could simply ride the Yamanote Line—a one-hour metro loop that delineates the central districts of the nation’s capital. You’d spot dozens of vastly different neighborhoods from the passenger windows: cross-streets that best New York’s Times Square in skyscraping neon, or more down-to-earth areas with mom-and-pop noodle shops that rattle when a train trundles by.

Try stepping off at any station that speaks to you and get a little bit lost. Despite its immense size, Tokyo is one of the safest cities in the world, and hidden in its maze of backstreets is a trove of chic boutiques and delicious izakayas—casual spots for eating and drinking. In a city so large, it can really feel as if many of these places are waiting to be discovered.

Read more: How to Eat Well in Japan: The Strategies You Need for a Delicious Trip

Use everything here as a jumping-off point to strike out on your own and make the most of your time. We’ve highlighted just a tiny slice of the trends, patterns and points of interest that Tokyoites covet, but you’ll still return home with keepsakes and stories to tell. Sure, you won’t be an expert on Japan or Tokyo—that will take years. But you’ll truly have been there.

Illustrations by Lauren Tamaki

Getting to the heart of most cities is something akin to peeling an onion; in Tokyo the exercise feels so limitless, it’s like trying to flake apart a croissant. But point your compass in the right direction, and you can pack lots of cultural edification into narrow pockets of time. Here are three optimized Tokyo walks you can use as building blocks to help make sense of the world’s biggest metropolis.

Japan’s penchant for bulldozing buildings and replacing them with new ones is best explored along Omotesando-dori, Tokyo’s Champs-Élysées. Its name roughly translates to “front approach street,” as it was—and still is—the main thoroughfare leading to the entrance to one of the city’s most important places of worship. (We’ll get to that later.) In the early 2000s, most of the residential structures that flanked the broad road were razed to make room for an ambitious luxury retail artery, which is now filled with a succession of architectural wonders. The Prada store (1) is a futuristic beehive by Herzog & de Meuron; Dior’s (2) slim, translucent boutique is an elegant exercise in form following function, designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning firm Sanaa.

Swerve off the main drag into a ramble of narrow side streets, and among the many thrift stores and hair salons you’ll find Tokyo’s best tonkatsu at Maisen (3). Its pork cutlets are the delicate and ultraflavorful result of true frying wizardry, drawing long queues for seats. But you can skip the wait by grabbing a to-go sandwich version, served between slices of the fluffiest milk bread, from Maisen’s street-side stall next door. Dessert will be waiting a couple of blocks over at Higuma Doughnuts (4), where the featherlight treats come in cinnamon, limoncello and other flavors.

Head back to the main drag and work your way farther west toward Harajuku Station. Just south of it you’ll spot a swooping conch-shelled structure by the entrance to Yoyogi Park. It may be the most significant piece of architecture in Japan: Designed by Kenzo Tange, the Yoyogi National Gymnasium (5) was the locus of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the first games that were internationally televised and a seminal opportunity for Japan to reestablish itself as a modern, postwar nation. Behind it you’ll find the 105-year-old Meiji Shrine (6). The complex of yawning pavilions is a serene place of Shinto prayer surrounded by a thicket of more than 100,000 hand-selected camphor, ginkgo and pine trees.

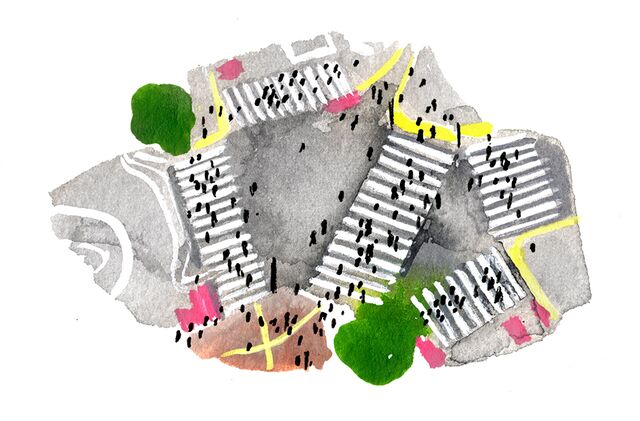

5 Yoyogi National Gymnasium

You’ve just wrapped a crash course on the last century of Japanese history, so reward yourself with a quick trip down Cat Street (7), one of the city’s most beloved pedestrian-friendly shopping lanes. (It’s packed with buzzy international labels such as On, Kith and Rapha.) It will zigzag all the way past Ryan (8), where you can indulge in a soothing bowl of soba, and then onward to Shibuya Crossing (9). No trip to Japan is complete without a scramble across the busiest pedestrian intersection in the world, where a million people are estimated to converge daily.

The northeastern area of Tokyo—called Shitamachi, or “low town”—was historically where commoners, craftspeople and merchants lived, in contrast to the higher elevations that noble and samurai families preferred. It’s one of the few parts of the city that wasn’t decimated by two cataclysmic events: the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923, which felled about 60% of Tokyo’s structures, and the air raids of World War II. The sprawling district retains its throwback charm with narrow lanes, low-slung shop houses and places of worship.

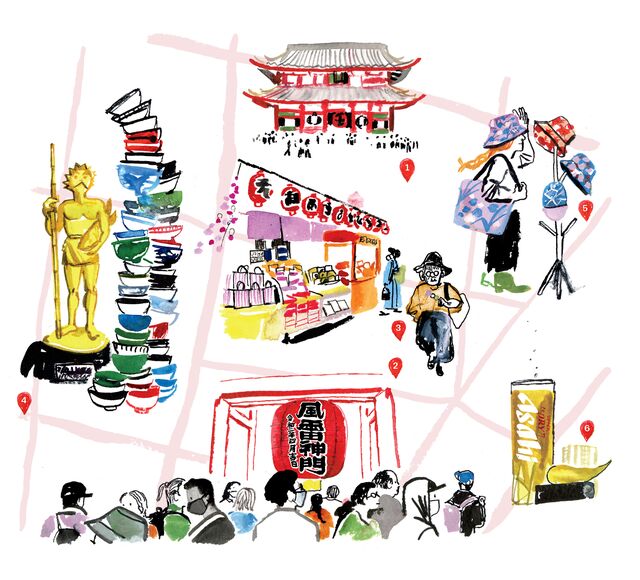

The Asakusa neighborhood is the easiest and most popular point of entry into Shitamachi, and within it is Sensoji Temple (1), Tokyo’s oldest Buddhist site. Enter through the Kaminarimon gate (2), a pavilion famed for its giant hanging lantern. As you work your way through the grounds toward the main house of worship, you’ll find Nakamise-dori (3), a shopping arcade where boutiques have been operating for generations. Lining their shelves are ema (small wooden plaques for written prayers) and traditional sweets like dango (skewered mochi dumplings) with kinako (soybean powder) and fried manju buns filled with red bean paste.

A few blocks over is Kappabashi (4), a long street of restaurant supply shops. Here you can go big on classic Japanese purchases such as Imari ceramic dishes, donabe rice cookers and chef’s knives, or browse more compact treasures like denim cooking aprons, plastic food replicas and little hashioki (chopstick rests).

Make time for one quick stop as you loop back toward Asakusa Station. At Kimono Reborn Tokyo (5), discarded kimono materials have been repurposed to adorn hats, satchels and shoes. Just as no two robes are the same, each piece here is unique.

It’s across the street from the Sumida River, one of the few waterways in Tokyo that hasn’t been paved over with roads. Note the Asahi Group Holdings Ltd. headquarters (6) on the far side of the banks: Its rooftop sculpture is meant to look like the froth on top of a freshly poured beer. Locals call it the Golden Poo. You’ll see why.

6 Asahi Group Holdings Ltd. headquarters

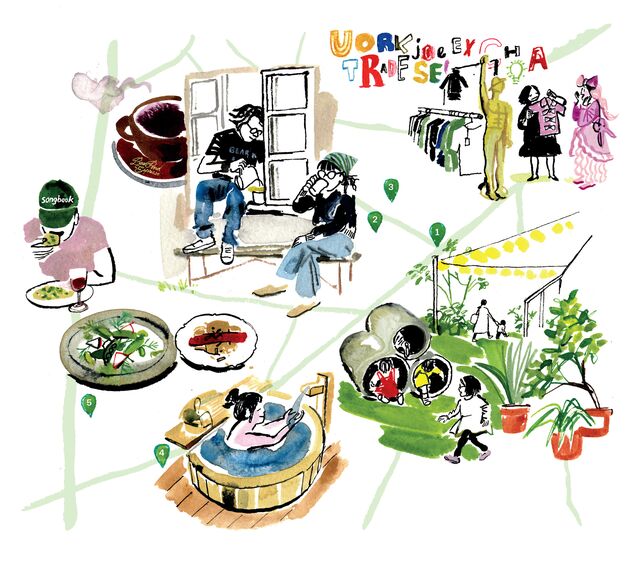

No city mints cooler-than‑cool neighborhoods more effortlessly than Tokyo, with 20-plus areas that easily one-up Brooklyn, New York’s Bushwick or East London’s Hackney in every regard. Shimokitazawa, or “Shimokita,” as the locals call it, has endured as the city’s gold standard of fashionable hoods. Located one metro stop from Shibuya’s mammoth transit hub, it stands out as a haven for younger Tokyoites and for its scenic Shimokita Senrogai (1) greenway, created when the Odakyu Electric Railway moved its tracks below ground.

Start with a jolt of espresso at Bear Pond (2), a stalwart of the local hipster scene where baristas are light on smiles and heavy on severe haircuts as they crank out frothy beverages made from the owner’s proprietary bean blend. Then it’s time to treasure-hunt your way through the district’s vintage shops. Even if you’re not a secondhand enthusiast, dip into at least one store to watch street fashionistas combing through pieces as if they’re panning for gold. Try New York Joe Exchange (3), which inhabits an old sento (public bathhouse)—you can spot the original tile work on the floor.

3 New York Joe Exchange

Cut through Shimokita Senrogai to see what kind of community programming is playing out on any given day. You may find a crafts fair, farmers market or gardening club. At the far end of the path is Yuen Bettei Daita (4), a newish hotel that’s styled like a traditional rural inn and features a real onsen bathing facility inside, with fresh mineral water piped in from the hills of Hakone. Day passes are available starting at ¥4,350 ($30)—the best way to slough off jet lag.

If lunch is in order, you’ll be right by Songbook (5), a serene spot where a musician-turned-chef works a wood-fired grill to churn out Japanese pizzas topped with duck confit and Kujo green onion or ume and prosciutto.

A few steps farther is Setagaya-Daita Station. Before leaving, take a moment to locate its west gate. On a clear day you’ll find an astonishingly perfect view of Mount Fuji. Unlike at other spots with similar postcard angles, you won’t have to climb a single stair to appreciate it.

Four places to zip through all your souvenir shopping, no matter who or what’s on your list

For gifts that fit in a carry-on

The Loft chain’s massive, multifloor stores are the perfect one-stop shop if you’re looking to fill your suitcase with J-beauty masks, bamboo bento boxes, washi paper greeting cards or Sanrio toys for the kids. The Shibuya flagship is the biggest of the brand’s 150-plus locations.

For fashion and design goods

Born in the 1970s on the backstreets of Harajuku, Beams Co. started out as an Americana concept shop bringing Ivy League-inspired fashion to Tokyo. It’s since grown into a go-to for Japanese craftsmanship—think wide-leg denim, block-printed scarves and bomber jackets. Of the 14 locations in Tokyo, Shinjuku’s is the one to prioritize: It’s like a Beams megaplex, complete with a design and art section.

Japan’s iconic department stores—such as Mitsukoshi and Matsuya, both in Ginza—are revered less for their luxury labels than for the elaborate depachika (food halls) in their basements. Search here for beautifully packaged gifts and brands such as the 300-year-old Ippodo Tea and the Toraya Confectionery Co., the official confectioner of the imperial family.

The Nihonbashi district has been a shopping haven since the Edo period (1603 to 1868), with generational businesses enduring since that era. Look for folding fans at Ibasen, handcrafted whittled toothpicks at Saruya and yukata (cotton robes) at Chikusen.

The Case for Eating in Train Stations

A Tokyo Station boxed-lunch shop. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

With 15 million locals shuffling through Tokyo’s subway and bullet train stations on a daily basis, Japan has perfected a system of high-quality grab-and-go eats for the taste-rich and time-poor. A lot about these venues may be surprising to visitors, beginning with the concept that fast-food chains and prepacked foods in Japan are a far cry from the ultraprocessed options at franchises in the West. And if handheld burgers and sandwiches make for speedy eats in other cities, noodles are the preference of Tokyo commuters.

You may recognize international ramen heavy hitters such as Ichiran, Ippudo and Afuri, chains that have sprouted up in the US and beyond. But check out domestic stalwarts Tenkaippin and Ramen Hayashida for preparations that may be harder to find abroad. The former does thick Kyoto-style chicken ramen, and the latter specializes in a clear soy sauce soup base, which locals will stop to slurp in less than 10 minutes.

Eating Thai noodles in Shinjuku Station. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

Metro stations are also low-stakes spots for expanding your culinary horizons. Among all the soba, udon, curry and rice bowl outlets, for instance, you’ll often find a special type of fast-casual fusion called wafu pasta. (It translates to “Japanese-style pasta.”) Here, spaghetti noodles may get topped with mentaiko (roe), natto (fermented soybean), sesame, yam or ume (plum), which may sound strange, but the premium ingredients really work. The best spots to try it are the ubiquitous Yomenya Goemon and Spajiro, both of which have outposts near major stations.

A mushroom-and-rice bento box. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

Rice balls in Shinjuku Station. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

For something more properly grab-and-go, you’ll want an ekiben, or train station bento box. It’s like a multicourse meal packaged into a small takeaway carton, typically found near the turnstiles at larger stations. Think of them as commuter picnics, containing a balanced mix of salads, skewers and sashimi (among other options).

Travelers peruse bento options. Photographer: Ben Weller for Bloomberg Markets

Ekiben tend to double as sort of tasting platters of the destination’s local ingredients and recipes. The ones you’ll find in Karuizawa, a popular weekending destination for well-heeled Tokyoites, might include the area’s famed burdock-root-and-mushroom steamed rice dish called toge no kamameshi, whereas you’re likely to find Kobe beef in Hyogo or bamboo-wrapped rice in Toyama.

And don’t overlook the iconic konbini. Often near train stations or inside them, these convenience stores have long dazzled foreigners. Despite what TikTok influencers might say, you won’t want to make konbini dining the backbone of your Japanese diet. But there’s no denying the appeal of an onigiri (rice ball) or a meronpan (melon-flavored brioche bun) when you can be in and out for ¥250 ($1.69) in 25 seconds.

Read next: Kyoto Travel Guide: Where to Stay, What to Do, See and Eat

More On Bloomberg

AloJapan.com