Architecture rooted in timber, stone and paper, gardens shaped with temple precision, a model of sustainable hotellerie within a UNESCO heritage site, and dining rituals framed by Yasaka Pagoda

Park Hyatt Kyoto: architecture layered into the hillside of a preserved city

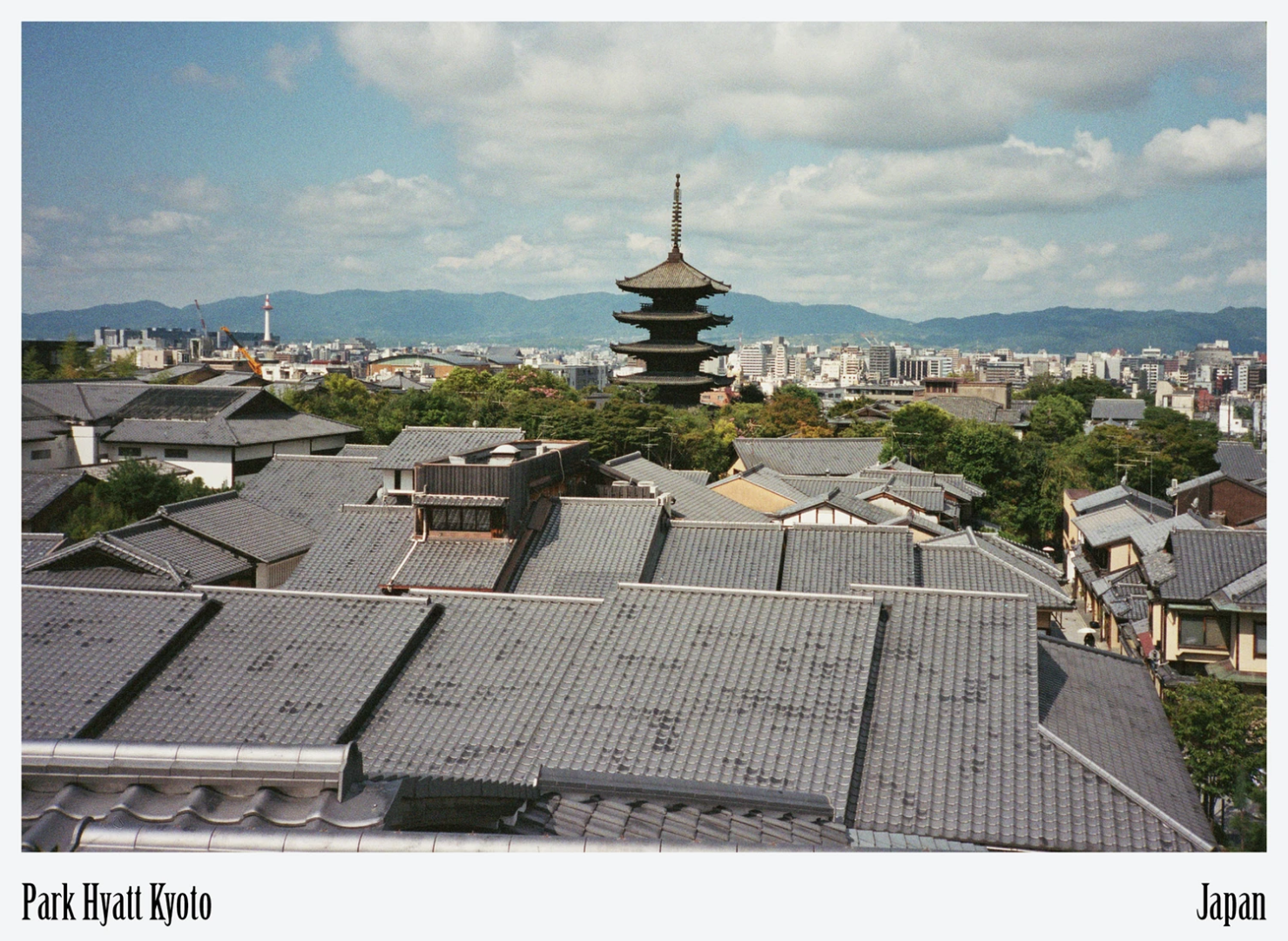

In the Higashiyama district, where the narrow streets rise towards Kiyomizu-dera and the tiled roofs frame Yasaka Pagoda, the Park Hyatt Kyoto was built with restraint. The hotel follows the gradient of the hill rather than dominating it, combining contemporary construction with the permanence of temples and townhouses. Opened in 2019, the property extends across a total floor area of fourteen thousand square meters on a site of over eight thousand square meters. Takenaka Corporation and Tonerico Inc developed a project that acknowledges both the geography of the site and the urban rules of Kyoto.

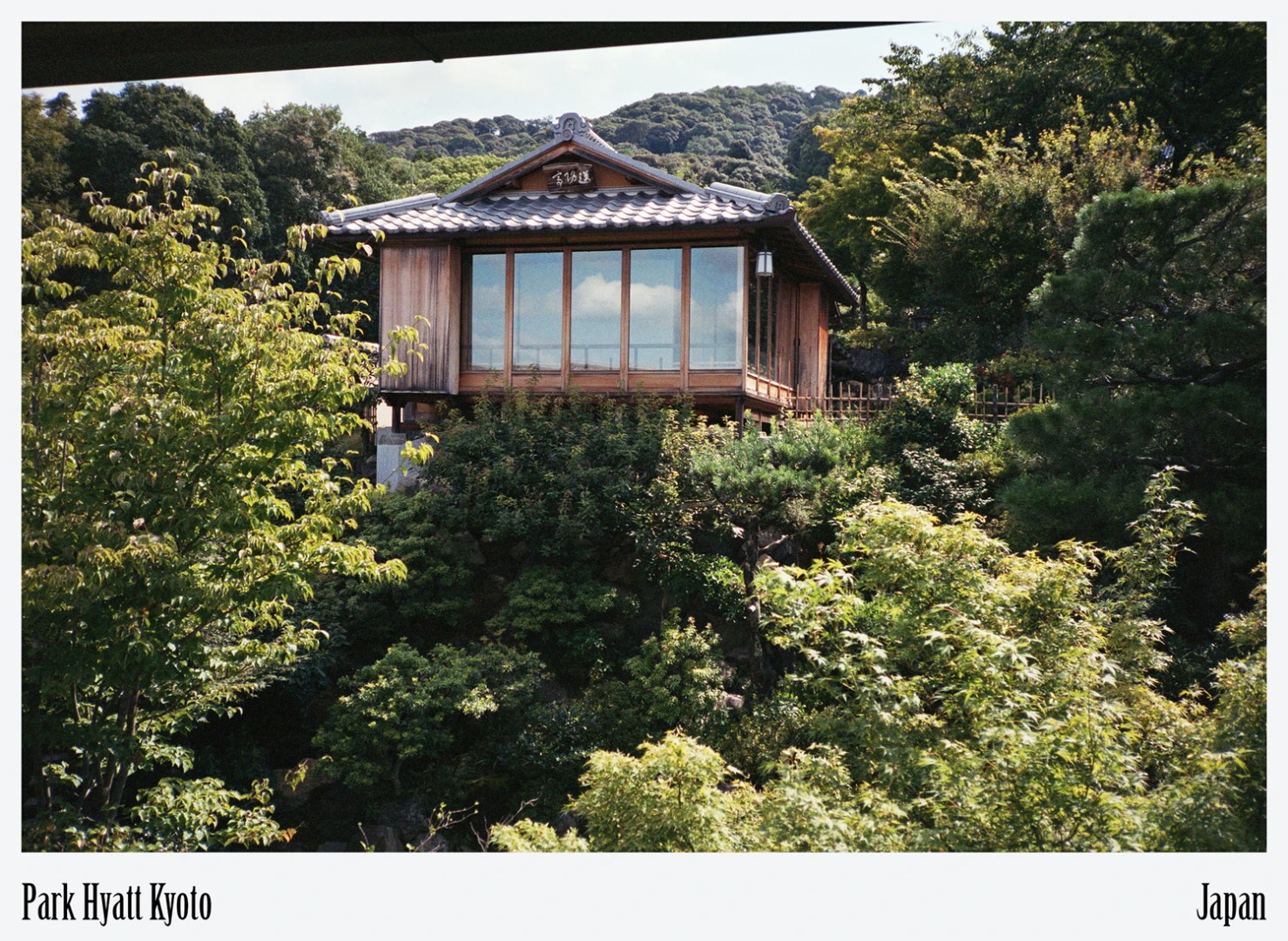

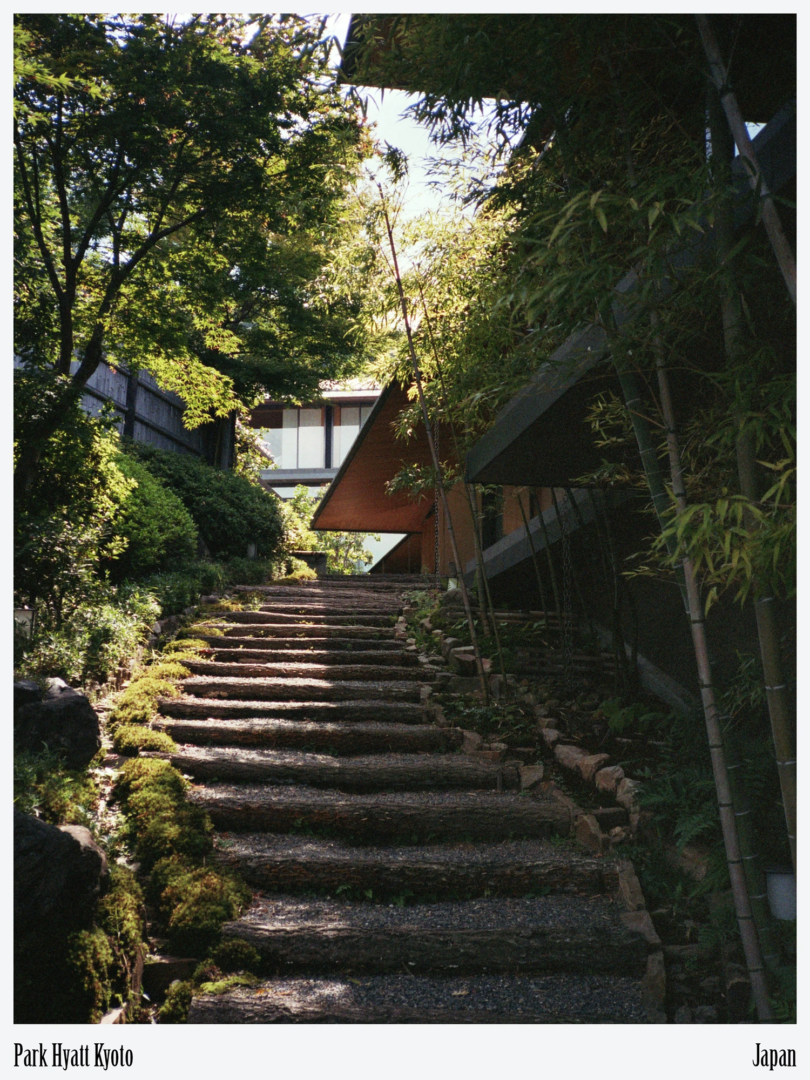

Organic architecture: embedding the hotel within the slope rather than above the skyline

Kyoto’s regulations restrict the height and massing of new buildings, preserving views of mountains and historical monuments. Park Hyatt Kyoto responds by stepping down the hill in terraces, a gesture aligned with the principles of organic architecture. The volumes are broken into separate wings, each low and narrow, reducing the impact of the hotel on the surrounding landscape.

The roofs are covered in traditional kawara tiles, and their incline mirrors the pitch of machiya houses. Gardens and courtyards punctuate the structure, so that stone paths, trees, and water channels interrupt the sequences of walls. Instead of a dominant landmark, the hotel appears as part of the hillside, a set of layers between forest and city. The project involved Takenaka Corporation as architect and Yasuo Kitayama as landscape designer, with interiors developed in collaboration with Tony Chi.

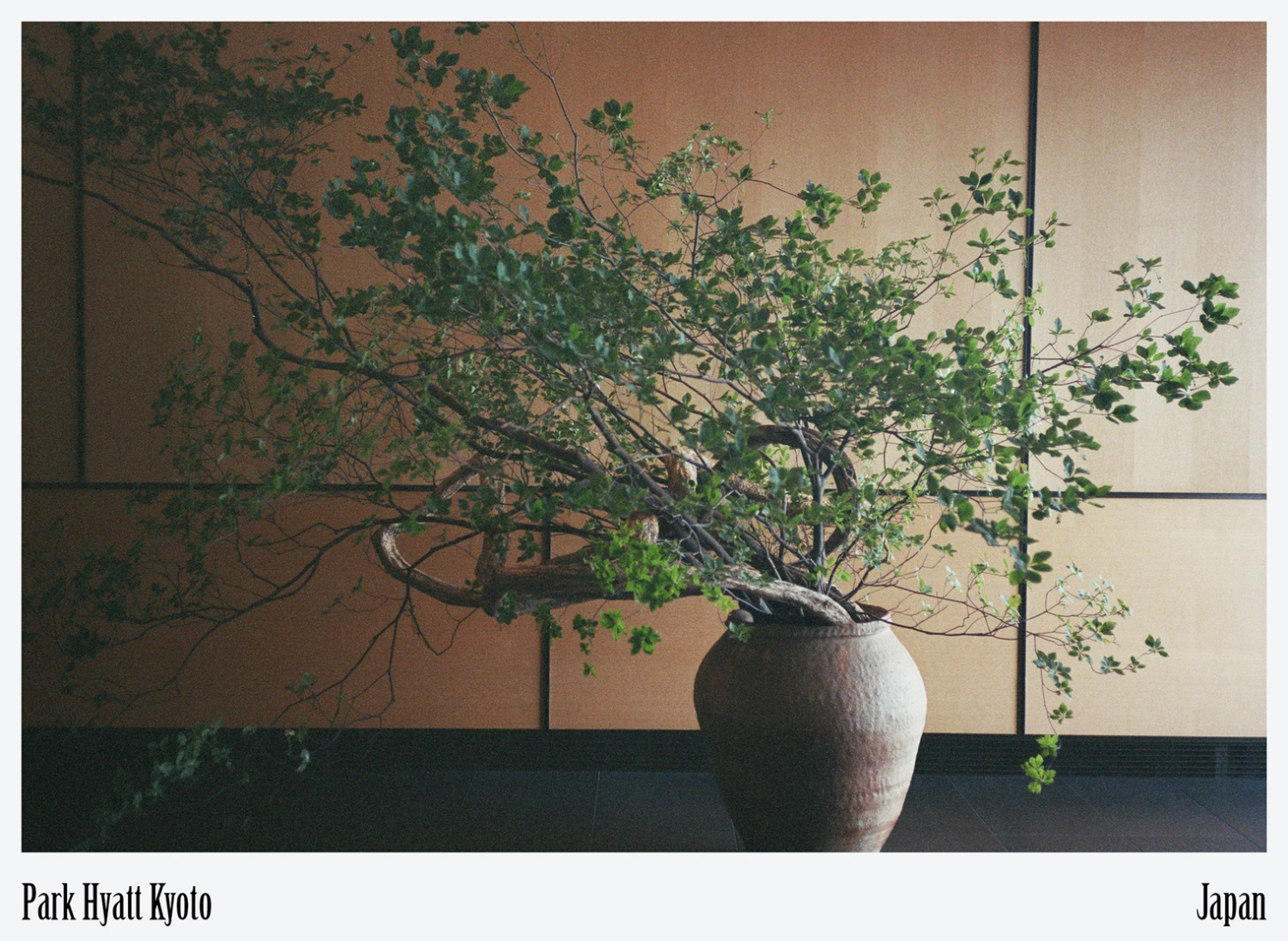

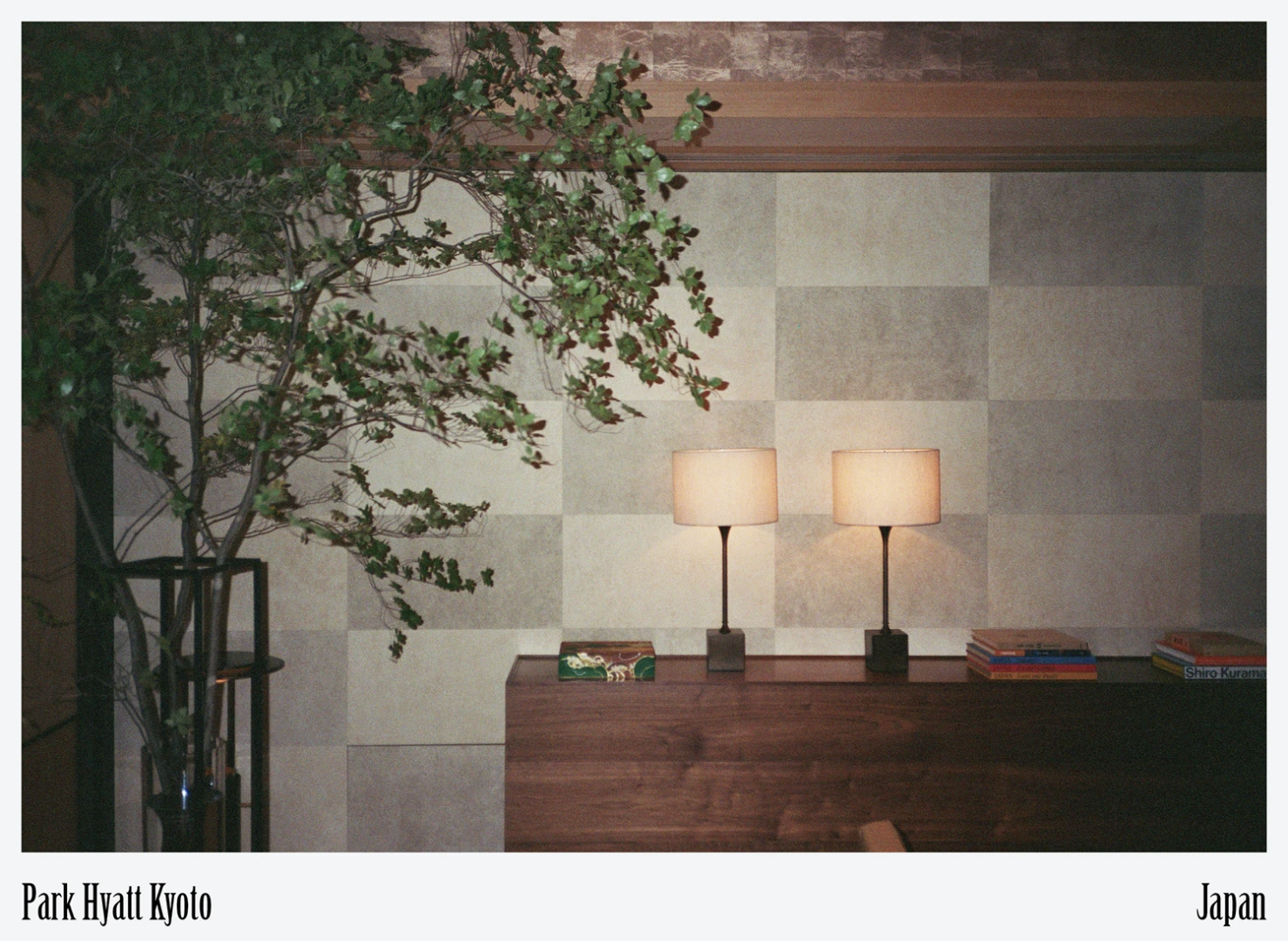

Raw materials: stone, timber and washi as continuity between craft and design

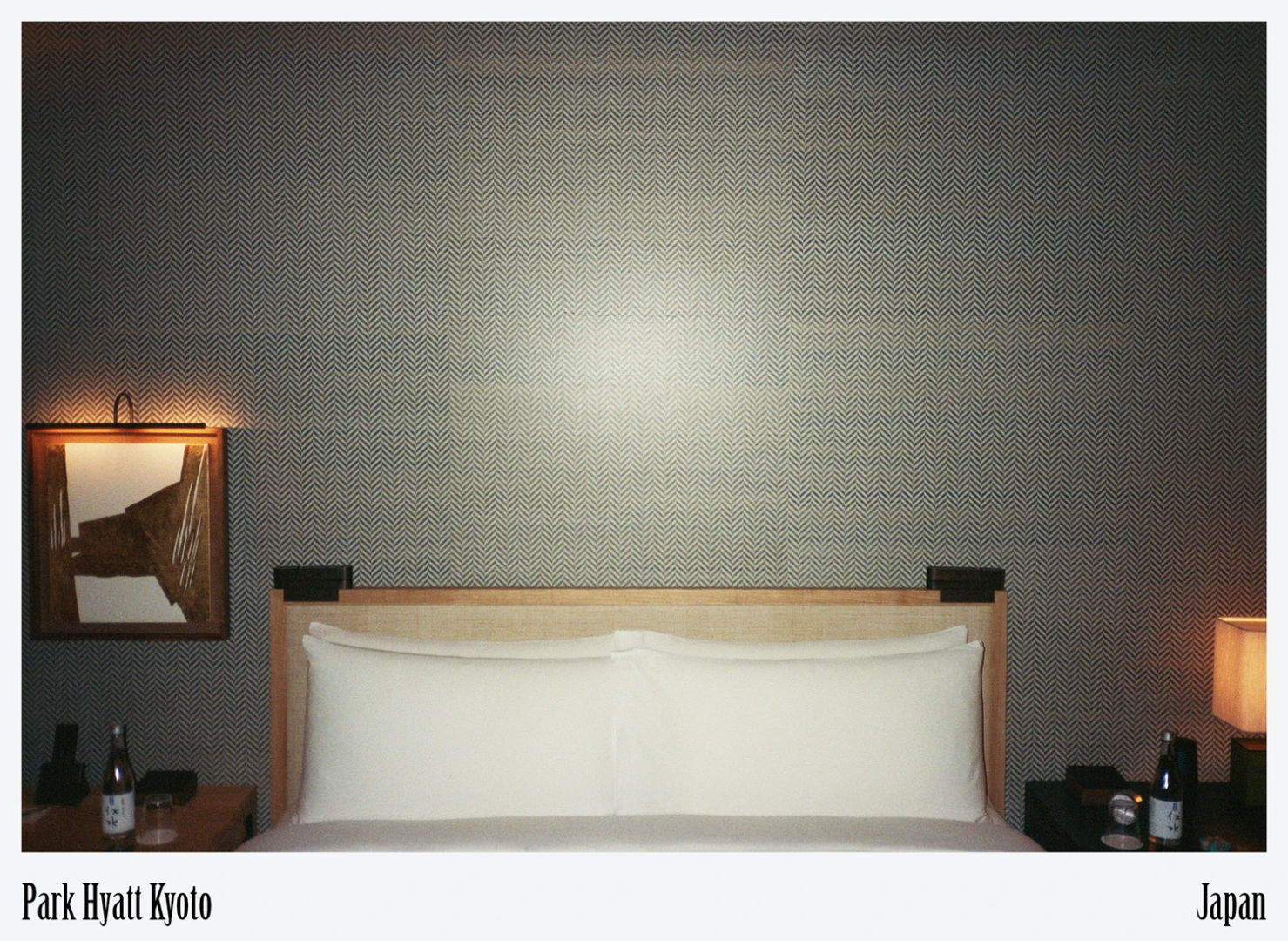

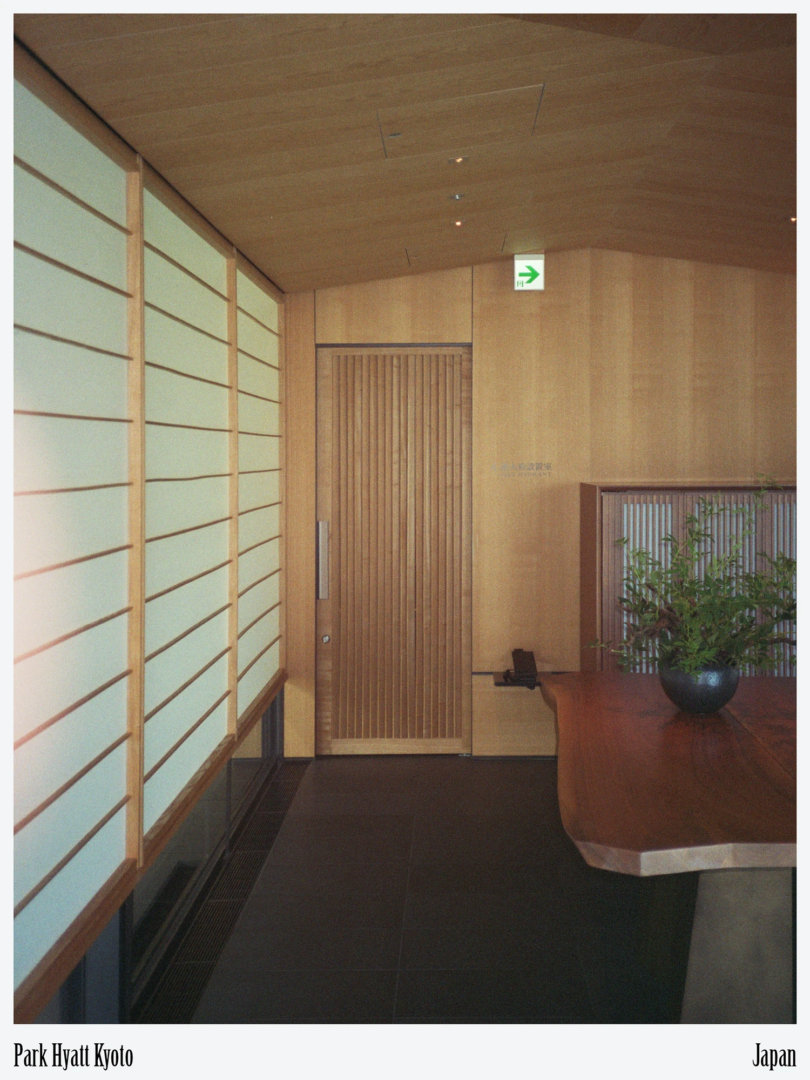

The architecture relies on raw materials chosen for their permanence and their cultural resonance. Hinoki cypress was used for exterior structures, while ash wood defines much of the interior carpentry. Stone from local quarries is set in pavements and in retaining walls, echoing temple precincts. Tatami mats and washi paper are applied to floors and sliding screens, referencing domestic traditions. Plasters with natural pigments soften the walls with muted tones. Interior walls also feature custom-made Manila hemp, dyed to create subtle tonal variations reminiscent of traditional Japanese plaster walls.

Bathrooms include granite surfaces: the Juparana stone was selected for its patterns resembling Japanese ink brushwork, with each slab carefully inspected to ensure calligraphy-like motifs.

Bronze and iron details reference the city’s craft heritage, while exposed timber joinery highlights techniques of Kyoto carpentry. In public areas, stone slabs alternate with polished wood, producing tactile contrast without ornamental excess. The choice of materials is both pragmatic and symbolic: long-lasting, repairable, and rooted in the city’s artisanal memory. Guests move through textures—rough stone, smooth paper, lacquered wood—that extend the continuity between contemporary construction and centuries of craft practice.

Ethics and aesthetics: balancing municipal rules with architectural expression

Building in Kyoto requires negotiation between regulation and design. The city imposes strict controls on signage, rooflines, and external materials. These rules express a civic consensus: preserving the integrity of views and monuments is considered an ethical obligation. For the Park Hyatt Kyoto, this meant adapting the project to limits rather than exceeding them.

The result is a form of ethics and aesthetics: ethical in its respect for skyline and neighbors, aesthetic in the way these limits shaped architectural choices. The collaboration with landscape architect Yasuo Kitayama extended the principle to gardens. Centuries-old pines, stone lanterns, and dry landscapes are maintained as part of the hotel’s grounds, merging with Kōdai-ji Temple’s environment. Architecture and garden design are not separate but continuous, forming a cultural landscape where new construction must serve more than its own function.

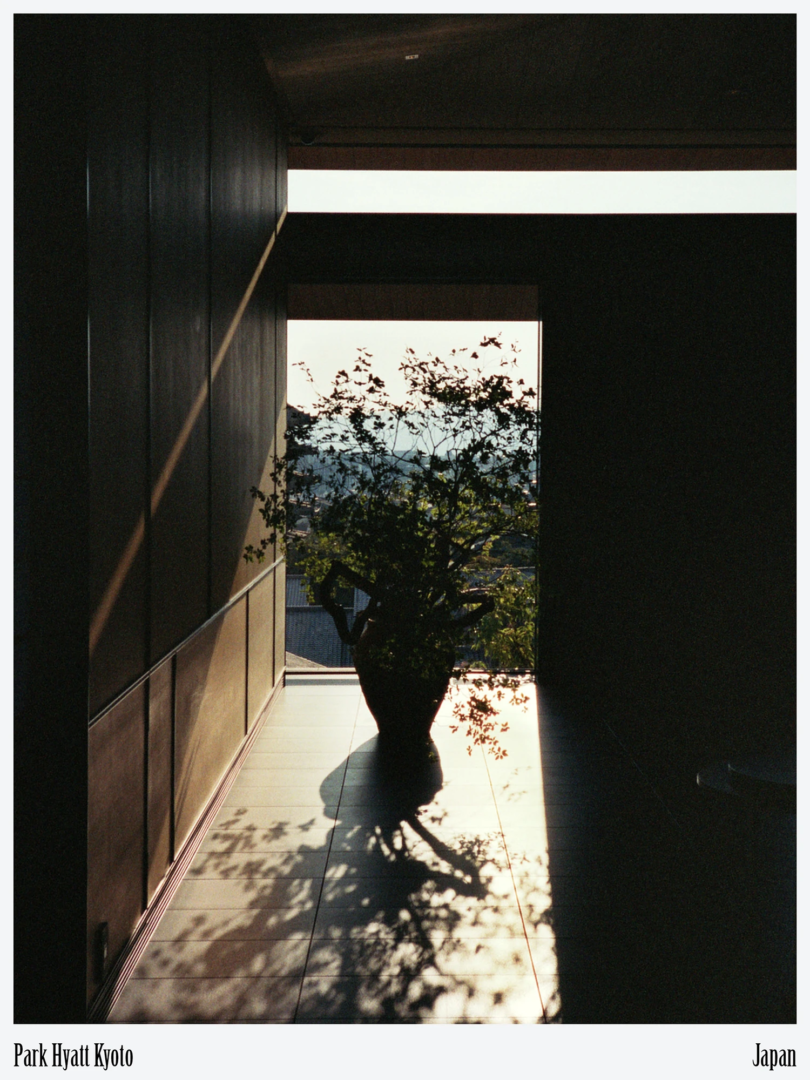

Sustainable hotellerie: designing a hotel within a UNESCO cultural landscape

The rapid increase of international visitors has pressured Kyoto’s infrastructure and threatened its historic balance. In this context, Park Hyatt Kyoto situates itself within the discourse of sustainable hotellerie. Instead of vertical expansion, the project relies on low terraced wings, each partially concealed by trees and gardens. Natural ventilation is favored through courtyards, while daylight enters rooms through wide windows, reducing dependence on artificial systems.

The use of renewable timber, combined with durable stone and tile, reduces maintenance and replacement cycles. The hotel’s low-rise structure aligns with Kyoto’s policy of limiting disruption to heritage scenery. Sustainability here is understood less as technological display and more as architectural restraint—building with the hill, using materials that age with dignity, and maintaining a scale compatible with its neighbors.

Yasaka: teppanyaki as culinary theatre framed by the pagoda

At the center of the dining offer is Yasaka, the teppanyaki restaurant. Teppanyaki, originating in postwar Japan, transforms the preparation of food into performance: ingredients are grilled on an iron plate before the guests, the sound of searing and the choreography of knives forming part of the meal. Yasaka extends this performative quality but frames it within Kyoto’s geography.

Large windows open onto the Yasaka Pagoda, so that each gesture at the grill is silhouetted against the city’s most recognized monument. The design of the space follows the hotel’s vocabulary of wood and stone, while the iron cooking surface becomes the central axis. Ingredients are sourced seasonally from Kyoto Prefecture, including vegetables, freshwater fish, and wagyu beef. Game deer and Kyo Tango rice are also among the ingredients used at Yasaka, while the hotel’s KYOTO BISTRO incorporates Kamo-nasu eggplants, Manganji peppers and Tamba chicken from local producers. At the Kohaku bar, the gin tonic is prepared with well water from the area. Teppanyaki’s modernity contrasts with the temples outside, yet the act of preparing food in view of guests recalls Kyoto’s tea ceremony culture: the ritual is as significant as the outcome.

Kyoto as cultural landscape: continuity of temples, streets and preserved views

For more than a millennium, Kyoto was the seat of the imperial court, shaping Japan’s political and cultural life. Higashiyama condenses this legacy: Zen temples such as Kennin-ji, the streets of Ninenzaka and Sannenzaka, and the gates leading to Kiyomizu-dera. The area has been recognized as part of the UNESCO designation “Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto,” where heritage is defined as cultural landscape—architecture, gardens, and natural scenery forming a single whole.

This definition affects contemporary construction. A new hotel is not judged in isolation but in relation to sightlines, rituals, and the symbolic meaning of its setting. Park Hyatt Kyoto, therefore, is part of a broader negotiation between the demands of global hospitality and the preservation of local identity.

Gardens and water: extending the language of Kyoto’s temple precincts

The gardens of Park Hyatt Kyoto, designed by Ueyakato Landscape, reference the vocabulary of temple courtyards. Stones are placed to guide movement, water basins reflect trees, and moss softens boundaries. The gardens, designed to evoke Japan’s satoyama woodlands, contain a variety of seasonal plants and trees, though the exact number of species remains unspecified. Water, present in small channels and pools, carries both functional and symbolic roles: cooling the courtyards, providing sound, and recalling purification rituals.

These gardens are not decorative additions but structural components of the architecture. By punctuating the terraces, they create sequences of interior and exterior, slowing the passage from public to private spaces. In Kyoto, where gardens act as cultural texts, their inclusion within the hotel situates it within a continuum rather than a rupture.

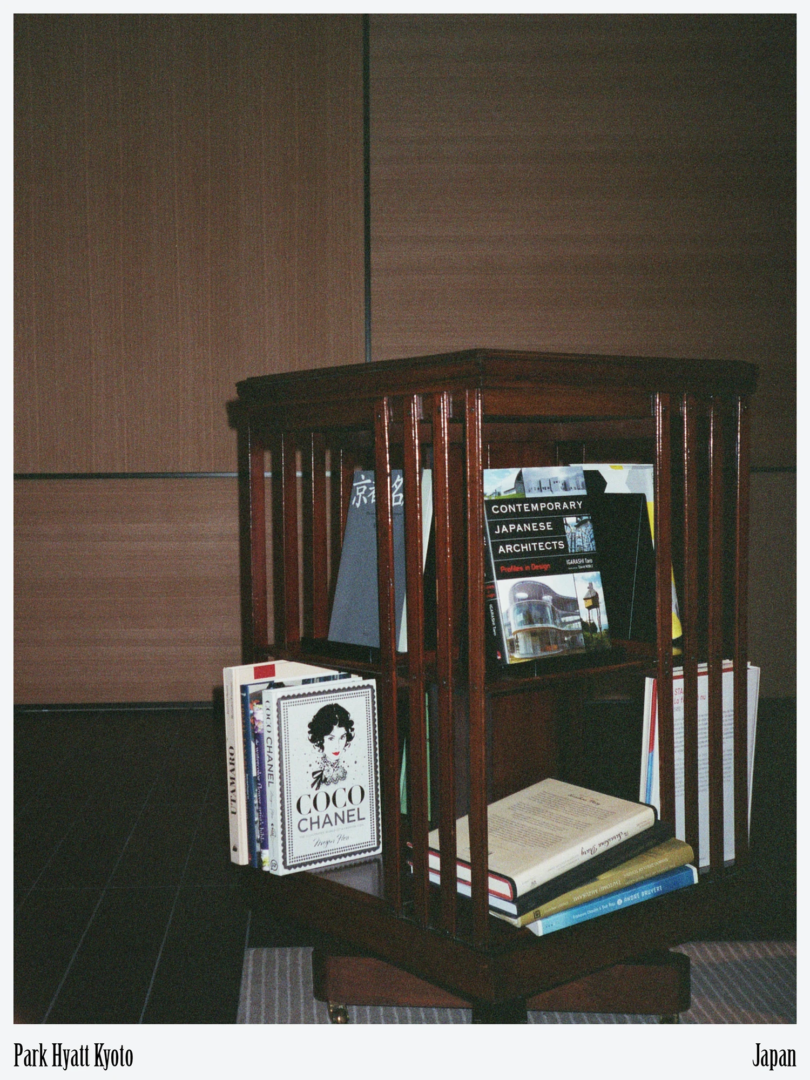

Craft traditions: embedding ceramics, textiles and joinery into a contemporary hotel

Kyoto’s artisanal heritage extends into the hotel’s details. Ceramics from Kiyomizu-yaki appear in tableware and ornamental pieces. Nishijin-ori textiles, woven with traditional looms, are used in fabrics and wall coverings. Carpentry follows local joinery methods, often left exposed as visible frameworks. Textiles include natural fibers such as cotton, wool and hemp, alongside blended fabrics; rattan is used for luggage racks, while natural fabrics cover headboards and daybeds.

The emphasis on material authenticity situates the hotel within the city’s craft ecosystem. Rather than importing generic luxury finishes, the project embeds itself into Kyoto’s production of ceramics, textiles, and woodwork. This decision reinforces the notion that hospitality spaces in Kyoto must carry traces of local culture in their material vocabulary.

Everyday rituals: how tourism intersects with Kyoto’s markets and festivals

Beyond temples and gardens, Kyoto is defined by its everyday rituals: morning markets at Nishiki, seasonal festivals such as Gion Matsuri, and the cycle of cherry blossoms and autumn leaves. These rhythms shape the experience of the city as much as monuments do. For visitors staying at Park Hyatt Kyoto, the hotel becomes a vantage point not only on landmarks but on the flow of ordinary life, visible in the streets and audible from the temple bells.

The presence of international hotels in this environment raises questions about how tourism intersects with daily practices. Kyoto’s challenge lies in maintaining the coexistence of global hospitality with local rhythms: markets still frequented by residents, festivals rooted in community rather than performance for outsiders. Architecture, in this sense, participates in protecting the conditions for these rituals to continue.

Architecture within limits: building in dialogue with continuity rather than rupture

Park Hyatt Kyoto demonstrates how architecture in the city functions within boundaries. These limits—of height, material, symbolism—constrain but also shape design. By accepting them, the hotel produces a form of international hospitality adapted to a historic urban context. It shows how new buildings can coexist with the continuity of temples, streets, and landscapes. Kyoto remains a city where architecture is less about individual statement and more about collective alignment with history.

In this perspective, Park Hyatt Kyoto may serve as precedent. For other heritage cities facing the pressures of mass tourism, it offers an example of how a global brand can adapt its form to a local grammar, prioritizing context over visibility. The hotel is not an isolated destination but part of a larger experiment: how contemporary architecture can contribute to the persistence of cultural landscapes rather than their erosion.

Park Hyatt Kyoto

Park Hyatt Kyoto is a low-rise hotel located in the Higashiyama district, built in collaboration with Takenaka Corporation and Tonerico Inc. The architecture follows the slope of the hillside, with terraced structures that integrate gardens and courtyards. Materials such as cedar, cypress, local stone, washi paper, and traditional tiles reference Kyoto’s craft traditions. The hotel features ninety rooms and suites, along with dining options including Yasaka, a teppanyaki restaurant overlooking the pagoda. It stands adjacent to Kōdai-ji Temple and within walking distance of UNESCO World Heritage sites.

AloJapan.com