Let’s begin with a question about Ehime Prefecture. Ehime is known for being situated along the Seto Inland Sea and is surrounded by beautiful mountainous terrain. The region also has a rich history tied to maritime industries, sea-based culture, and citrus farming.

Many of our 7.5 million readers may not be familiar with Ehime, so could you start by telling us a bit about the prefecture’s history, geography, and developmental background?

Certainly. Let me begin by discussing the history of Ehime Prefecture. The oldest recorded aspect of our history dates back roughly 3,000 years, and it’s connected to Dogo Onsen—our most famous hot spring. While we can’t say with certainty that the hot spring was being used exactly 3,000 years ago, we’ve found archaeological evidence—such as Jomon-era pottery shards—near Mount Kammuri, where the current Dogo Onsen administrative office stands.

These findings strongly suggest that people were living in the area during the Jomon period and likely benefitted from the natural hot springs. That’s why we proudly say Dogo Onsen has a 3,000-year history.

The name “Ehime” itself was first officially recorded more than 1,300 years ago, and it appears in ancient texts like the Kojiki. Incidentally, “Ehime” in ancient Japanese refers to a “lovely maiden.”

Roughly 1,200 years ago, we saw the beginning of the Shikoku Pilgrimage, a journey through 88 sacred sites believed to have been initiated by Kobo Daishi Kukai. This spiritual route still attracts many international travelers today.

About 400 years ago, construction began on Matsuyama Castle, which is now a major tourist destination alongside Dogo Onsen and the pilgrimage route. These landmarks have survived centuries of change and continue to shape the historical identity of Ehime.

Dogo Onsen • Matsuyama Castle • Henro

Could you give our readers a geographical overview as well?

Absolutely. Ehime is located on Shikoku, one of Japan’s four main islands, and is the northwesternmost prefecture on the island. The northern side faces the calm, island-dotted Seto Inland Sea, while the southern coast features rugged, ria-style shorelines.

The prefecture is also mountainous, including Mount Ishizuchi, the tallest mountain in western Japan. The area boasts the Shikoku Karst, one of Japan’s three major karst plateaus, and a collection of 391 islands that make our seascape remarkably beautiful.

Japan welcomed 36.9 million visitors last year and was ranked the top destination in the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Development Index. The Japanese government is now targeting 60 million visitors and ¥15 trillion in spending by 2030, as part of a strategy to revitalize regional areas.

Ehime has major tourism assets like Dogo Onsen, Matsuyama Castle, and the Shimanami Kaido cycling route. Among these, what do you see as Ehime’s strongest tourism appeal? What would you emphasize most to international visitors?

Before I answer directly, let me touch on some numbers. While the national target is 60 million visitors, we’re currently at 36.9 million, meaning there’s a gap of 23 million to fill.

The major urban areas—Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka—are already struggling with overtourism and simply cannot absorb that additional volume. This means regions like Ehime, which still have capacity, will need to play a central role in future tourism growth.

As of 2024, we had about 4.37 million overnight visitors to Ehime, of which only about 452,000 were international tourists. That places us 27th nationally, so there’s significant room to grow.

We’re currently investing around ¥1.3 billion annually in tourism promotion, and we’re doing that through various initiatives and regional tourism organizations.

One of our key strategies is based on a campaign we call “If you’re tired, come to Ehime.” The phrase “tired” can mean many things—physical exhaustion, mental burnout from repetitive routines, screen fatigue from office work, or simply emotional fatigue.

We want to offer healing through four key experiences:

Hot springsNatureHistoryFood

We’ve broken our tourism promotions down along these lines to reach people who are looking for recovery and meaningful experiences.

That’s a powerful message. You mentioned the Shimonada Station as one of your most iconic tourism spots. Could you explain why?

Shimonada Station is probably the most iconic representation of our identity. It’s a simple seaside station—just a small roof structure really—but it’s known as one of the closest station to the ocean and one of the best places to view the sunset over the sea.

It’s not extravagant. We haven’t poured huge sums of money into it. But the moment you stand there and watch the sun go down, you feel time slow down. It’s emotional, almost spiritual. It represents exactly what we want Ehime to be: a place where people heal without needing extravagance.

Shimonada Station

In Japan, cultural sites like Harajuku, Dotonbori, or Mt. Fuji have become mainstream cultural landmarks. For Ehime, aside from Dogo Onsen and Shimanami Kaido, are there hidden gems you believe have strong potential for global recognition?

Yes. One example would be Oyamazumi Shrine on Omishima Island. It holds over 80% of Japan’s National Treasure swords and armor in its treasure hall. Surprisingly, even most Japanese don’t know this.

Nearby, there’s also the Murakami Suigun Museum, which tells the story of the Murakami pirates. These two sites, if promoted together, could introduce international visitors to Japan’s samurai heritage in a compelling, authentic way.

In fact, several international cruise operators have already visited and shown strong interest in building shore excursions around these cultural assets.

Let’s imagine a 5–10 day itinerary for international travelers starting from Matsuyama Station. What would you recommend?

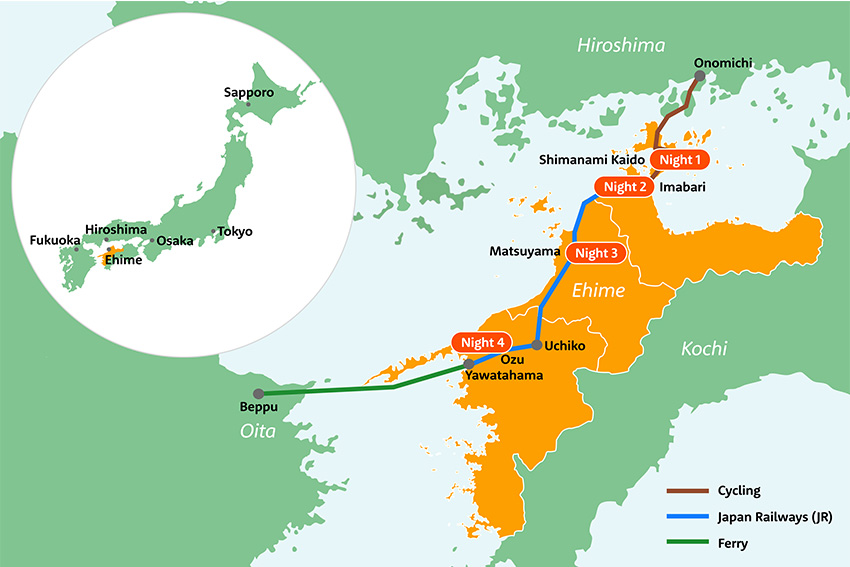

Actually, many visitors arrive via Hiroshima, not Matsuyama. From Hiroshima, they can go to Onomichi, which is the starting point of the Shimanami Kaido cycling route.

From there, they can spend 1–2 days cycling across the islands. Then, they can continue on to Matsuyama to explore Matsuyama Castle and Dogo Onsen.

From there, they can go southwest to Ozu and Yawatahama, and then take a ferry to Kyushu. This creates a smooth, one-way route that covers key parts of both Shikoku and Kyushu, without having to double back.

Shimonada is very popular, but there are concerns about over-tourism—parking shortages, limited access, etc. What measures are you taking?

We’re not at over-tourism levels yet. But we’re preparing. It’s not just about numbers; it’s also about manners and behavior.

We’re working to educate international visitors about Japanese norms, and we’re studying models like Fukuoka City, which developed “hands-free tourism” services to store luggage and reduce congestion on public transport.

As visitation grows, we’ll apply similar strategies here.

Let’s talk about the Shimanami Kaido cycling route. What is your vision for its future?

Back in 2010, Shimanami Kaido wasn’t widely known. But in 2013, our governor launched an international cycling event where we closed down a section of the expressway so cyclists could ride it. It was the first time this had ever been done in Japan.

It was logistically demanding—at the cycling event in 2013, we had to put up and remove cones and signage within three hours. On the day of the event, it rained, and it almost didn’t succeed. But we managed to clear everything with four seconds to spare. That moment sparked something and this became a major turning point for the main cycling event to be held from 2014 onwards.

Thereafter, with the support of the local community and the regular holding of ‘Cycling Shimanami’ events since 2014, Shimanami Kaido has become a symbol of adventure tourism in Japan. It has even attracted migrants—people relocating to start tourism businesses catering to cyclists.

We’ve also formed partnerships with international cycling organizations like Bike New York and Bike New South Wales, and in May 2027, we’ll host Velo-City, one of the world’s most prestigious cycling conferences—marking the first time it’s ever been held in Japan.

Cycling Shimanami

We heard from leaders in places like Koyasan that they are targeting high-end travelers. How about Ehime? Who is your target audience?

Great question. Let me use a simple market pyramid model. At the top, you have the ultra-wealthy, in the middle the affluent, and at the base, the general public.

It reminds me of the Swatch Group’s brand strategy. At the bottom, they sell affordable watches that fund the business. At the top, they have luxury brands like Breguet, but the volume comes from the lower tiers.

So while we certainly want to attract affluent travelers, I think it’s risky to focus only on them. We want to build a strong foundation that includes everyday travelers who can sustain local economies long-term.

Finally, what are your long-term goals for tourism-driven regional revitalization in Ehime over the next 5–10 years?

One example is in Ozu City, where the NIPPONIA Hotel has helped breathe new life into the area. We want to support more entrepreneurial efforts like that.

Another case is the silk industry in Nomura Town, once a major hub of Japan’s textile sector. While 95% of the industry has disappeared, it produced high-quality silk allegedly once used in items as prestigious as the coronation garments of Queen Elizabeth II.

Today, we’re seeing innovation in silk used for biomaterials, cosmetics, and food, and an ambitious local company is working to revive the industry.

Through tourism and product development, we want to rebuild local pride, generate new jobs, and attract sustainable investment over the next decade.

Nipponia Hotel

AloJapan.com