Megumi Takezawa knows exactly what she wants: a three-bedroom apartment of at least 70 square meters, built to withstand earthquakes, in a safe neighborhood within commuting distance of central Tokyo — and priced somewhere between ¥60 million and ¥70 million ($400,000 to $467,000).

That may have been realistic a decade ago, but not today. In Bunkyo Ward, where Takezawa lives, even outdated units of that size — ones that don’t meet modern earthquake standards — now start at nearly ¥90 million, well beyond what she and her husband can afford. For the 43-year-old office worker and mother of a young child, the search for a new family home is in limbo.

“Our current place is only 50 square meters, and it feels too small with a child,” she says. “I’d like to move as soon as a good property comes on the market, but the prices are completely unrealistic.”

Like many Tokyoites, Takezawa is caught between the need for more space and record-breaking housing costs. She wrestles with difficult trade-offs, like giving up convenience for a place in the suburbs, or leaving the capital altogether — a move that might affect her child’s education, her job and her aging parents.

“I agonize over this every single day,” she says.

Apartment prices in Tokyo have been climbing for more than a decade, fueled by historically low interest rates that made bigger mortgages manageable. The pandemic added fresh pressure, with demand for extra rooms to accommodate remote work and soaring construction costs driving both new and older units higher.

With the yen weak, overseas investors now see real estate in the capital as relatively inexpensive by global standards. Their focus on prime central locations has amplified price gains in the most desirable neighborhoods, further straining affordability for local buyers, a trend the government has begun to acknowledge.

A decade ago, a household

with earnings of ¥8 million could afford to buy a condo in central Tokyo. Now it takes closer to ¥20 million.

| LILY PISANO

“In recent years, rising construction costs driven by higher material prices and labor expenses, along with steady housing demand in highly convenient areas have pushed up the prices of newly built condominiums, particularly in urban centers,” Land Minister Hiromasa Nakano said during a Sept. 2 press conference, adding that secondhand condominium prices are also trending upward.

“We are also aware of voices pointing out the possibility of condominium transactions being carried out for speculative purposes … and speculative trading that is not based on actual demand is undesirable,” he said. “We intend to closely monitor real estate market trends to ensure such practices do not become widespread.”

Speculation and strain

Nakano’s comments came in response to a rare plea from Chiyoda Ward, a central Tokyo district that is home to the Imperial Palace, government offices and many corporate headquarters.

On July 18, the ward issued a formal request aimed at curbing speculative condominium purchases, asking the Real Estate Companies Association of Japan, a trade group made up of major developers, to attach special clauses to apartments built as part of publicly funded redevelopment projects — including a five-year ban on reselling units.

Chiyoda Ward warns speculative condo deals risk driving both home and rental costs higher, pricing out residents and leaving more units empty. Such vacancies, it adds, can strain building management associations and undermine the quality of local neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the resale condominium market in Tokyo has also been surging. According to a survey by real estate research firm Tokyo Kantei, the average price of a secondhand condominium in Tokyo’s 23 wards, converted to a 70-square-meter unit, exceeded ¥100 million for four consecutive months through August, up 38.3% from the same month a year ago.

What it calls the “central six” wards — Chiyoda, Minato, Chuo, Shinjuku, Shibuya and Bunkyo — averaged nearly ¥170 million. By contrast, southwestern wards such as Shinagawa and Setagaya averaged around ¥90 million, while northern and eastern wards came in closer to ¥69 million, showing how demand in central Tokyo continues to push the overall average higher.

Central Tokyo generally includes the six wards of Chiyoda, Minato, Chuo, Shinjuku, Shibuya and Bunkyo.

| GETTY IMAGES

“As new condominium prices climb and the supply of new units dwindles, buyers who are squeezed out are shifting their focus to relatively new resale properties,” says Masayuki Takahashi, senior chief researcher at Tokyo Kantei. “Owners, aware of the strong demand, are listing aggressively — often at ambitious price tags of 10% to 15% higher.”

Tokyo Kantei tracks a “resale value” index measuring how much newly built condos have appreciated over the past 10 years. Across greater Tokyo, nearly all properties now exceed a score of 100, with some doubling or even tripling in value over the past decade, Takahashi says.

“This is highly unusual,” he says. “Normally, apartments in Japan lose value as they age, but in this case, asset values have ballooned, reversing the typical depreciation cycle — a truly exceptional stage in the market.”

The trend is even more pronounced for newly built condos. According to the Real Estate Economic Institute, the average price of new condominiums released in the 23 wards in August climbed to ¥138.1 million, surpassing the ¥100 million mark for two months in a row, driven by large-scale, high-end projects.

Takahashi says a decade ago, households earning ¥8 million could afford a central Tokyo condo; today, only families with annual incomes around ¥20 million remain in the market. For comparison, the national average household income in 2023 was ¥5.36 million, according to the labor ministry, while households with children averaged ¥8.2 million — figures likely lower than the typical incomes seen in Tokyo. Foreign investment has accelerated the momentum. A white paper on land released in May reported that overseas investors spent ¥939.7 billion on Japanese real estate in 2024, a roughly 63% increase from the previous year, accounting for about 17% of domestic investment.

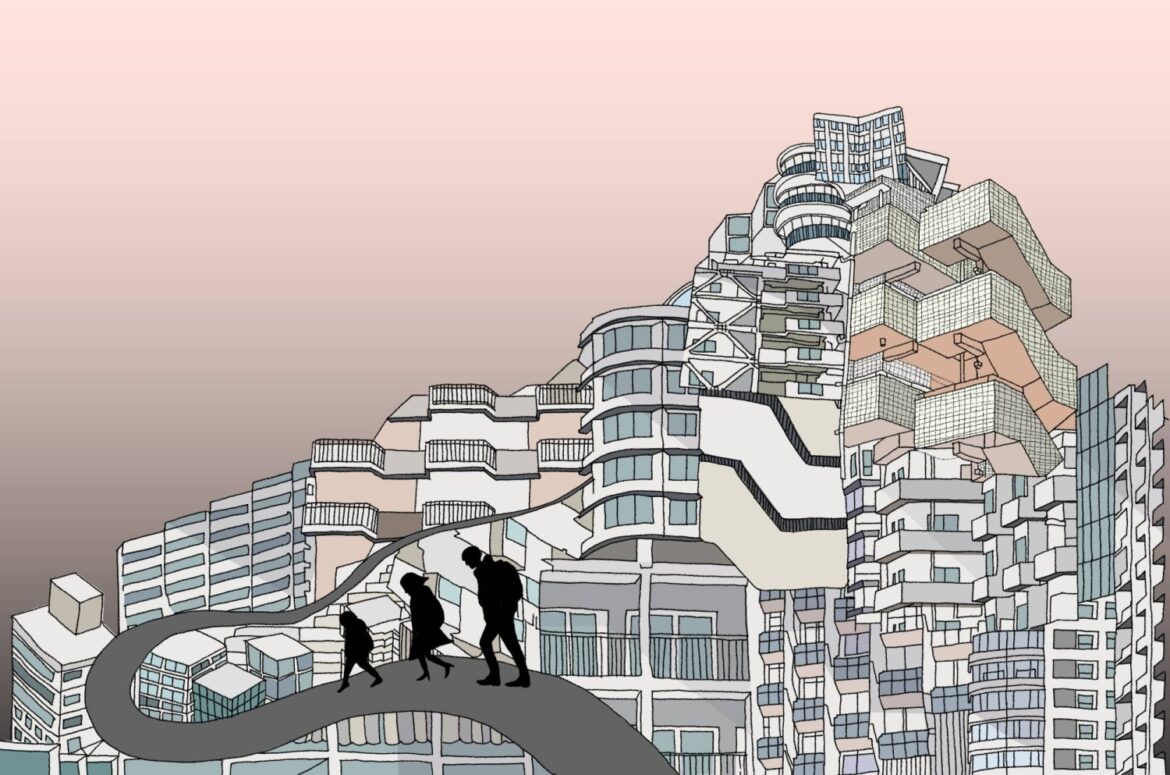

With central Tokyo increasingly out of reach, many buyers are shifting focus to the suburbs. But demand spillover is pushing up prices in Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba prefectures, even if they remain more attainable than the 23 wards.

The ‘の’ rule

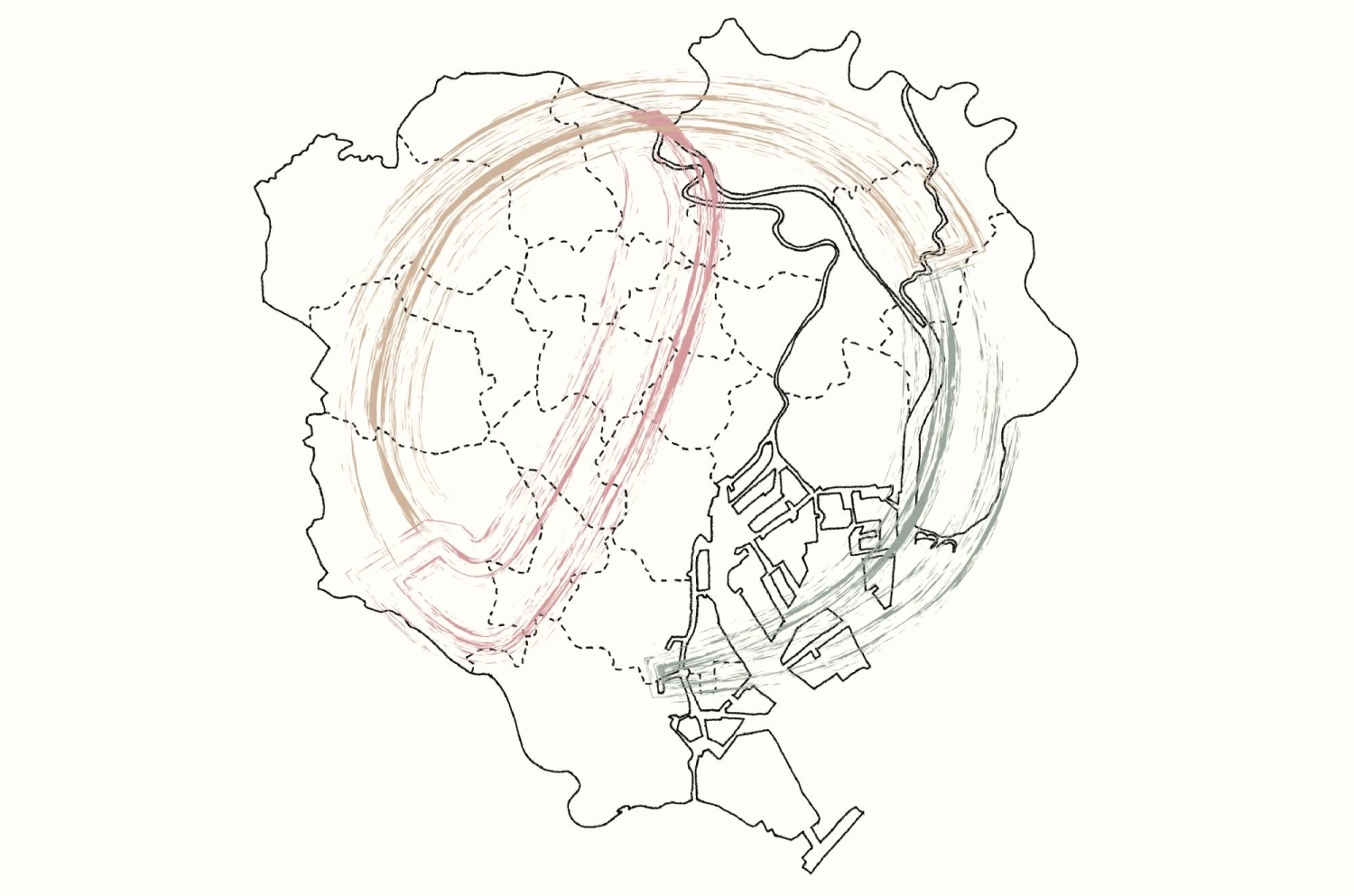

In Japan’s real estate industry, there’s something known as the “の” (no) rule: Prices in Tokyo don’t climb everywhere at once, but trace the looping path of the hiragana character.

In Tokyo’s 23 wards, increases are said to begin in the old urban core around Edo Castle — places like Chiyoda, Chuo, Minato and Shinjuku — before moving southwest into Shinagawa and Meguro. From there, the wave spreads west to Setagaya and Suginami, north to Nakano and Nerima, then up to Itabashi and Kita, and finally east to Katsushika and Edogawa.

Tokyo property prices traditionally rise first at the city center, then ripple south, west and east. But remote work and a weak yen have upended the cycle.

| LILY PISANO

The same arc held across the metropolitan area: central Tokyo first, then Kanagawa, on to western Tokyo and Saitama, before looping into Chiba. For decades, brokers have said the rally ended there, but history shows the rule isn’t absolute. During the asset price bubble of the late 1980s, the wave reached Chiba only to curl back, sparking another surge in central Tokyo — a second “の” etched across the map.

Now, with both new and secondhand condos in central Tokyo already above bubble-era peaks and still climbing, those in the industry say the old playbook no longer applies.

“Right now, price growth in Tokyo’s Joto area is remarkable,” says Naoya Yamamoto, chief operating officer at Sakura Home Inspection, referring to the historically working-class eastern wards now being redeveloped. “This year’s roadside land value survey shows property prices rising in Asakusa and Kitasenju. Within the 23 wards, these neighborhoods are still seen as relatively affordable, so demand is growing.”

Yamamoto traces the surge back to 2012, when Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s second administration introduced aggressive economic stimulus measures dubbed “Abenomics,” followed by the Bank of Japan’s ultra-loose monetary policy in 2013. Lower mortgage rates let buyers shoulder larger loans — and purchase more expensive properties — setting prices on an upward trajectory ever since.

Remote work led many workers to consider getting apartments with rooms they could turn into makeshift offices, a costly addition to their rental expenses.

| GETTY IMAGES

The pandemic, which many expected would cool the market, only accelerated prices. Remote work made renters realize they needed an extra room for an office, often an additional ¥50,000 to ¥100,000 a month in rent. With mortgage rates still near record lows, many decided it made more sense to buy, driving prices higher still.

Even now, with inflation strong and the BOJ having scrapped its decade-long stimulus program and nudged up short-term interest rates, buyers keep bidding. Many are betting inflation will persist and property will only grow more expensive. Foreign investors, meanwhile, have returned after a pandemic lull, drawn by a weak yen that makes Tokyo look cheap next to other global capitals.

“Prospective condo buyers who can no longer afford units in Tokyo’s 23 wards are turning their attention to nearby, well-connected suburbs — the so-called second-best areas of Saitama, Kanagawa and Chiba,” Yamamoto says, pointing to redevelopment projects in particular. “Take Sagami-Ono in Kanagawa, the terminus of the Odakyu Line, for example. Plans for a 41-floor high-rise there have already sparked a surge in inquiries, signaling a shift in market trends.”

If that shift continues, he adds, it could upend the traditional “の” pattern. “Even locations slightly farther out can see rising prices if they offer growth potential and good access to the city. That makes this a phenomenon worth watching.”

A wait-and-see mentality

With both new and secondhand condo prices at record highs, many prospective buyers are staying put. At the same time, more people are relocating for work, school or transfers after the pandemic slowdown, adding pressure to the rental market. The problem is, rents are climbing too.

With demand unrelenting, Tokyo renters are facing record prices and dwindling options, forcing many to stay put for now.

| LILY PISANO

According to real estate information service At Home, the average listed rent for single-occupant condominium-style apartments (known in Japan as manshon) of 30 square meters or less in the 23 wards rose to ¥103,952 in August, up 0.7% from July and 10.6% from the same month last year — the 15th straight month of record highs.

In fact, rents stayed or climbed across all apartment sizes. Units for couples (30 to 50 square meters) averaged ¥169,768, up 0.6% from the previous month. Family-size apartments (50 to 70 square meters) stood at ¥247,375, while larger units over 70 square meters rose 0.5% from July to ¥392,192.

Shiori Kawada, a real estate agent active in Bunkyo and Taito wards, says many renters are feeling trapped by soaring rents.

“I often hear people saying how their current rent is the cheapest they can get, so even if they want to move, they can’t,” she says. “Others feel they have no choice but to move farther out.”

The surge reflects unrelenting demand. Even after the spring moving season, which marks the start of both the school year and the fiscal and corporate year, renters who held off are still searching, while a new wave enters the market ahead of autumn. Landlords are also seizing the moment. Rising labor and cleaning costs, along with fewer available units as tenants stay longer to avoid hefty moving fees, have made rent hikes easier to push through.

“Whether they must move or just want to, everyone seems to be playing it safe with rentals, except for those with plenty of budget to spare,” Kawada says. “The overall mood is that ‘there’s no need to buy right now.’”

AloJapan.com