Kazue Nakamura is seen in Osaka Prefecture, May 19, 2025. (Mainichi/Tomonari Takao)

OSAKA — A 76-year-old woman born to an Okinawan mother and a U.S. serviceman who had been concealing her own origins for many years to avoid prejudice and discrimination realized that she had inherited “treasures” from her parents after coincidentally reencountering her high school classmates.

Kazue Nakamura, a former child care worker living in Osaka Prefecture, kept her Amerasian heritage hidden for most of her life. She struggled for many years, unsure of how to reconcile with her own roots or with whom to share her feelings.

After graduating high school, Nakamura left Okinawa Prefecture. While working at a spinning factory in Takaishi, Osaka Prefecture, she attended a vocational school to study child care for three years. Her days began with a 4:30 a.m. siren, starting work at 5 a.m., with a pause for breakfast before heading to school in the afternoon. To obtain her child care qualification, she also took piano lessons on her days off to prepare for the practical piano exam. “I was determined to seal away my Okinawan identity to become a mainlander,” she recalled.

Hiding ‘3 things’

Nakamura passed the civil service exam in Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward and worked at a child care center there. One day, a colleague asked, “Why did you come to Tokyo when child care administration is more advanced in Osaka?”

The reason was that she wanted to get as far away from Okinawa as possible. However, after about a year of working in Tokyo, she moved back to Osaka Prefecture, where she had settled during her group employment. She married and had three children. However, she tried to hide three things from her workplace and neighborhood: that her father was American, that she was an orphan, and that she was from Okinawa Prefecture. She was mindful of her language to avoid giving herself away.

Amid this, an event occurred that allowed Nakamura’s closed heart to open.

In the spring of 1992, her alma mater, Yomitan High School, made its first appearance in the Senbatsu invitational high school baseball tournament. Invited by a friend, she casually attended a game at Hanshin Koshien Stadium in Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture. The stands resonated with her nostalgic school song and finger whistles, and the Okinawan dialect filled the air. She felt a sense of lightness.

“Kazue, is that you?” “You’ll come to the reunion, right?” Her former classmates said to her after encountering them for the first time in a while. She thought, “I am indeed Okinawan. I might have been trying too hard. I should think that Amerasians can also be Okinawans.” It had been about a quarter of a century since she left Okinawa.

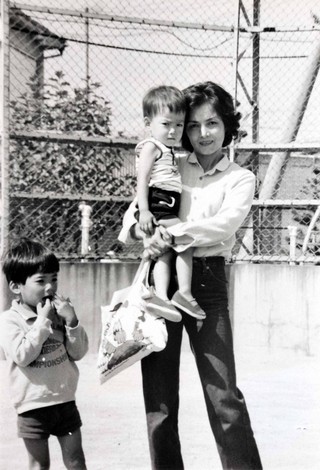

Kazue Nakamura holds her third son in Osaka Prefecture in the early 1980s. On the left is her second son. (Photo provided by herself)

She then began actively seeking “Okinawa.” She visited Osaka’s Taisho Ward, where many Okinawans reside, and made new acquaintances at Okinawan restaurants.

She met a young person playing Ryukyu (Okinawa) folk songs on the “sanshin” traditional stringed instrument and began attending a sanshin class led by the individual. Most of the participants were “mainlanders” with no blood ties to Okinawa. Meeting people captivated by the richness of Okinawan culture filled her with joy.

Phrase that stirred her heart: ‘That’s fine as you are’

Nakamura started returning to Okinawa frequently and began learning about the issues the region faces. At a gathering, a man’s words profoundly moved her.

Although he realized Nakamura was Amerasian, he did not mention it. About six months after their meeting, he quietly said, “You have the Okinawan spirit of empathy and compassion, along with the rationality of your American father. That’s fine as you are.” She realized that she had inherited treasures from her parents, whom she had wanted to hide.

However, she still could not openly communicate this to her three children. She hesitated, unsure of how to start the conversation.

In 2005, a symposium on Amerasians in Okinawa was held in Osaka. It was a gathering to discuss the current situation and challenges, featuring the organizer of the Amerasian School in Okinawa, an alternative “free school” in Ginowan, Okinawa Prefecture. Even roughly 40 years after Nakamura left Okinawa, cases persisted of Amerasian children struggling to fit in at school due to parental divorces and other issues. The Amerasian School in Okinawa, which opened in 1998, aimed to teach children the languages and cultures of both Japan and the United States, encouraging them to take pride in being “double.” Children are enrolled in public schools, and going to the free school counts as public school attendance, allowing them to graduate. This system was a victory for Amerasians’ parents.

Nakamura was asked to speak at the symposium as an Amerasian, and she accepted. She shared her painful childhood experiences and addressed the issues surrounding U.S. military bases. She wanted to convey her feelings to her peers in the younger generations and emphasized, “Even if you were born as a result of war, you must absolutely never do anything that leads to war.”

Son: ‘Mom, you had it tough too’

That day, Nakamura’s second son was in charge of the sound system at the venue. Through the microphone and earphones, she revealed her background to him for the first time. Her son simply said, “Mom, you had it tough too.” However, she still has not spoken face-to-face with her children about it, as tears would make it difficult for her to speak.

In 2018, Denny Tamaki, who was running for Okinawa governor at the time, addressed his supporters, saying, “My father is American, and my mother is from Okinawa.” Tamaki’s father was a U.S. soldier who returned home before he was born. Nakamura saw her own situation reflected in Tamaki’s and thought, “I never imagined such a time would come.”

Last summer, Nakamura returned to Okinawa. She attended a meeting organized by the Yomitan village history editing office to learn the dialect of the prefecture. There, a woman in her 30s approached her and said, “I’m actually a quarter (American).” She explained that her father is Japanese but her mother was born to an American man and an Okinawan woman. She confided that her mother was reluctant to speak about her roots, yet she looked cheerful.

This is the only photo of Kazue Nakamura, left, with her mother, Teruko, taken when Kazue was 2 or 3 years old. (Photo provided by Kazue Nakamura)

“When I asked a volunteer for a DNA test, I found out my mother’s father’s name, birthplace and even his face. Although the relatives were no longer alive, I discovered the location of his grave,” the woman said. She then recommended a DNA test to Nakamura. But Nakamura replied, “I’m OK. It’s too late now.”

However, her curiosity began to grow. While watching a film starring American actor Gregory Peck, she imagined her father’s face. Last fall, with the U.S. presidential election being held, she had more opportunities to see maps of the U.S. on TV. As she looked at the screen with states colored red for Republicans and blue for Democrats, she thought, “Perhaps it would be OK to know my father’s birthplace. Knowing his name wouldn’t disadvantage my children. On the contrary, it might broaden my world.” She called the woman she met at the study group and said, “I think I’ll go ahead and request a DNA test too.”

Sense of closure

In December last year, Nakamura visited a private home in central Okinawa Prefecture. There, she met a retired American veteran and his Japanese wife, who were volunteering to help with DNA testing activities. They carefully explained about the test to Nakamura, as if sensing her feelings. She provided a sample of saliva in the test kit they gave her. Once she handed it over, the couple immediately sealed it. The sample has already been sent to the U.S., and the volunteer network is searching for a match. Apparently, it could take one to two years, and sometimes no match is found. Nakamura felt a sense of closure. “I’ve done everything I can,” she thought.

In June, Nakamura met a few Amerasian women about 30 years younger than herself. One of the women had met her own American father and visited her mother’s grave together. However, another woman spoke of regrets and tragedies, saying, “Even if they find their father, some refuse to meet or contact them. Some people lament, feelings of being ‘abandoned twice,’ and suffer greatly.”

Nakamura has yet to receive her DNA test results. Various thoughts swirl in her mind, like, “I wonder what kind of life my father led. If he remarried, maybe I have a younger sister or brother.”

Nakamura has never seen her father’s face. There seemed to be a photo, but her grandmother tore it up when her mother passed away. She hopes for at least one photo to place beside the only picture she has with her mother.

Nakamura hopes the test results will one day reach her, bringing an end to the long “night.” She wonders what kind of scenery it will reveal. Her heart races with mixed feelings of anticipation and anxiety.

(Japanese original by Tomonari Takao, Expert Writer, Osaka City News Department)

(This is the second part of a two-part series.)

AloJapan.com