Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

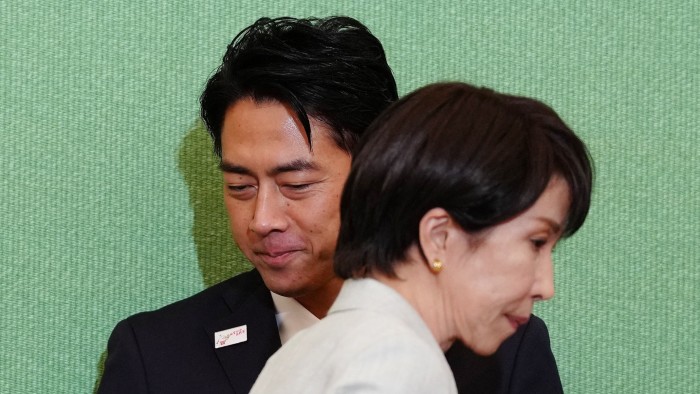

Victory for either of the two frontrunners in the leadership election for Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic party will make for a standout moment in the political life of the world’s fourth-largest economy. If 44-year-old agriculture minister Shinjiro Koizumi wins on October 4 and is appointed prime minister, he will be the country’s youngest head of government since the great reformer Hirobumi Ito took office back in 1885. If conservative veteran Sanae Takaichi prevails, she will be Japan’s first female premier.

Yet as the short and largely inconsequential tenures of numerous recent Japanese prime ministers suggests, it will not be easy for Koizumi or Takaichi to make a more substantive impact. Japan is in the throes of a tricky transition to persistent inflation and suffering from fiscal strains, demographic decline and geopolitical uncertainty.

Under outgoing Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, who lasted barely a year in office, the LDP lost control of both houses of parliament. The long-dominant party is struggling to fend off new populist right-wing rivals. Its loss last October of the lower house majority it previously enjoyed in coalition with junior partner Komeito means the new LDP president will even have to rely on opposition disunity to secure the prime ministership.

At least Koizumi, son of former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi, and Takaichi, acolyte of late premier Shinzo Abe, have obvious models for how an LDP politician can change the political weather. Both the elder Koizumi and Abe were able to articulate clear personal visions for the party and nation, and were ready to fight hard against vested interests to achieve it. Junichiro Koizumi made postal privatisation a symbol of Japan’s ability to reform. Abe, during his second stint as PM, shored up confidence in the economy by packaging anti-deflationary fiscal spending and easy monetary policy together with promotion of freer trade and a bigger role for women in the workplace.

Big-picture vision is distinctly lacking among the LDP leadership frontrunners, however. Koizumi has prioritised lifting incomes by pressing for wage increases and by raising income tax thresholds to match inflation. This makes sense; it is important that the public do not come to associate current moderate inflation rates with lower living standards. Using the prime ministerial bully pulpit more effectively to push companies to increase pay and putting more pressure on prefectures to raise current far-from-generous minimum wage levels would help too. Koizumi is also right to step back from LDP promises of cash handouts that risked fuelling doubts about Japan’s fiscal sustainability for little lasting benefit. But it is hard to discern a bold new economic agenda in his campaign so far.

As for Takaichi, though she has rowed back on calls for a consumption tax cut, her fiscal stance is more worrying. A devotee of “Abenomics”, she has been a vocal advocate of monetary easing and fiscal expansion, two of the “three arrows” that made up her political mentor’s flagship policy. But with inflation now back and interest rates positive, there is no case for fiscal irresponsibility. Takaichi needs new arrows for her quiver.

Winning back public confidence in its economic stewardship is vital for the LDP. But balancing the conflicting impulses of a party that is always a broad ideological church is a tireless task for Japanese premiers at the best of times. Failing to set strong personal priorities at the outset means they risk getting lost in day-to-day firefighting. Koizumi and Takaichi should remember that it may be hard to set out a big vision during a leadership campaign, but it will get even harder if they win.

AloJapan.com