The period between 1945 and 1952 was an odd one in Japan’s history. The country’s cities and economy had been devastated by the victorious Allied forces during World War II. Under the paradoxical promise of American liberation, Japanese artists faced a dilemma that could influence their careers in uncertain ways: align with the occupier’s ideals, or resist to maintain their artistic autonomy.

Japanese artists did both — yet modern art history has struggled to address a contradictory artistic output that engaged with Japan’s history, modernization, and occupation. Alicia Volk’s new academic book, In the Shadow of Empire: Art in Occupied Japan (2025), is a successful corrective to this lack.

In five richly illustrated chapters, Volk offers a deeply researched analysis of dissonant art practices in occupied Japan. Central to the book’s argument is an exploration of how Japanese artists working across media such as printmaking, painting, and sculpture navigated domestic and foreign political pressures and economic upheaval, while also exercising personal agency.

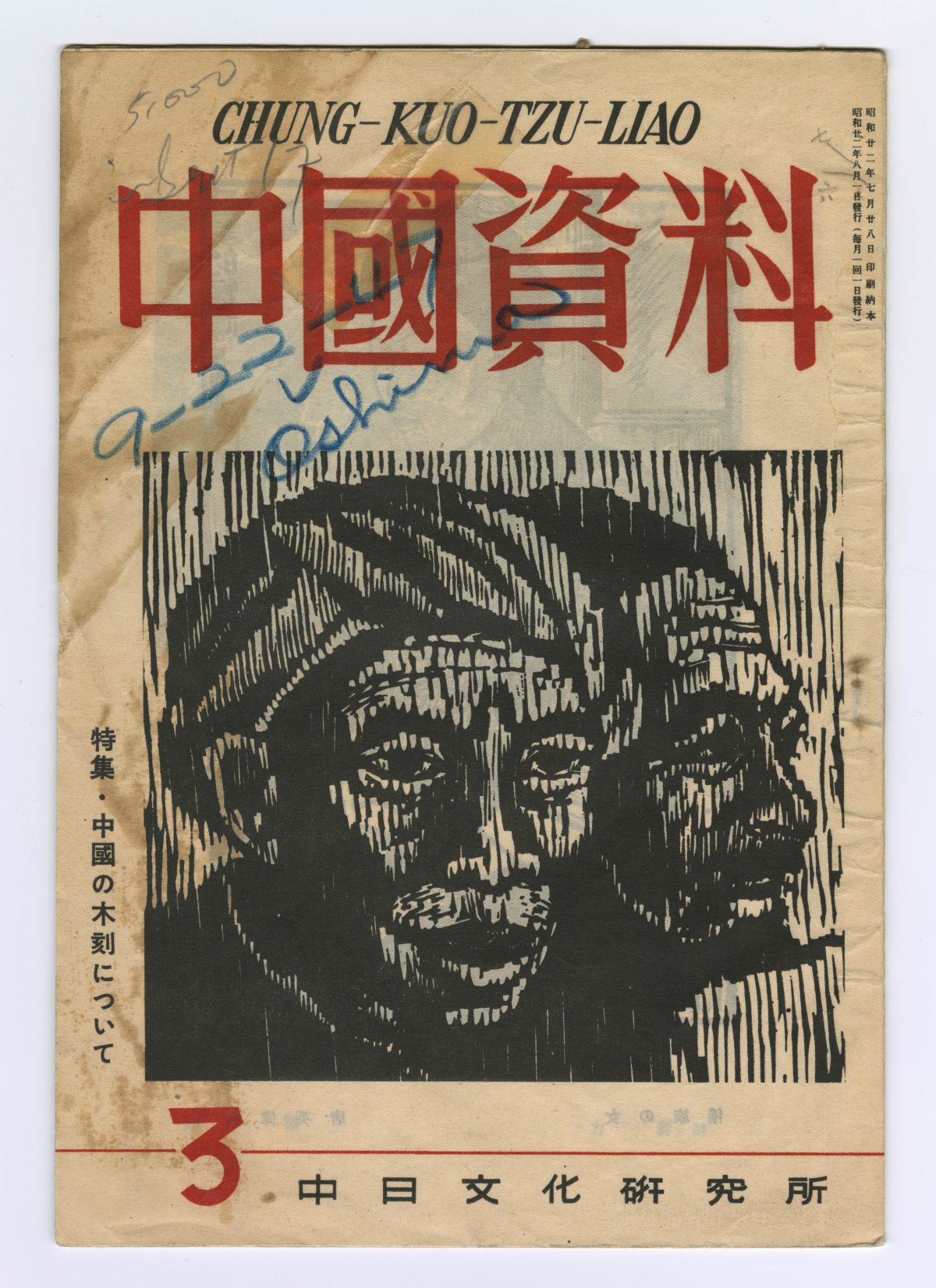

Cover of Chūgoku shiryō (August 1947), featuring detail of woodcut by Wang Renfeng, “Impression of Farmers (Nōmin inshō)” (undated)

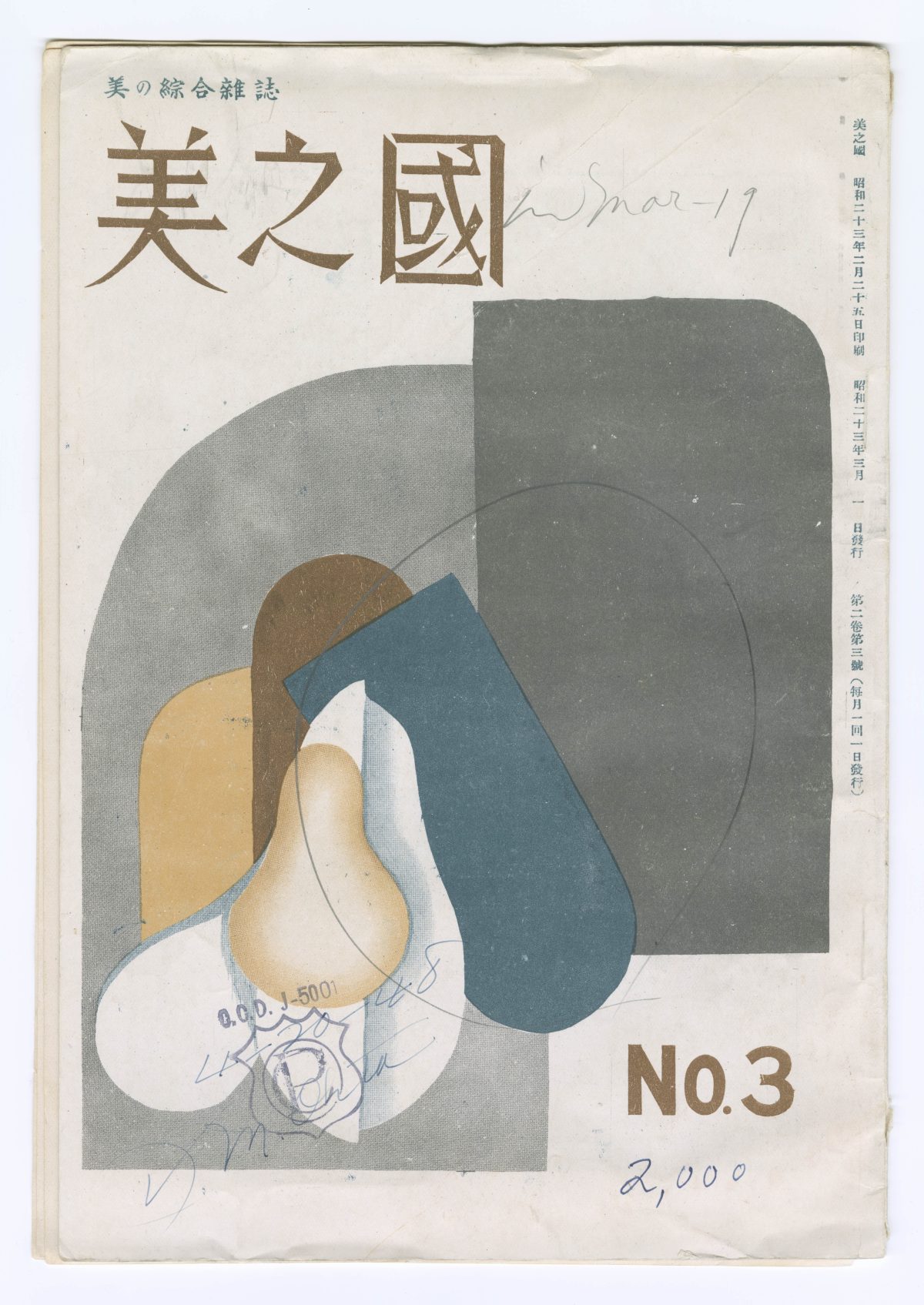

Inspired by expressive European painters like Kandinsky and Munch, Japanese artist Onchi Kōshirō became a driving force behind what would become popularly known as “creative prints,” which supported a new, democratic artistic reputation of the nation internationally, first through images of peaceful Japanese festivals and later abstract forms. Other artists such as Suzuki Kenji and Iino Nobuya devoted themselves to what is known as “people’s prints,” focusing on grief and toil-stricken depictions of local farmers and workers in a more introspective exploration of postwar Japan.

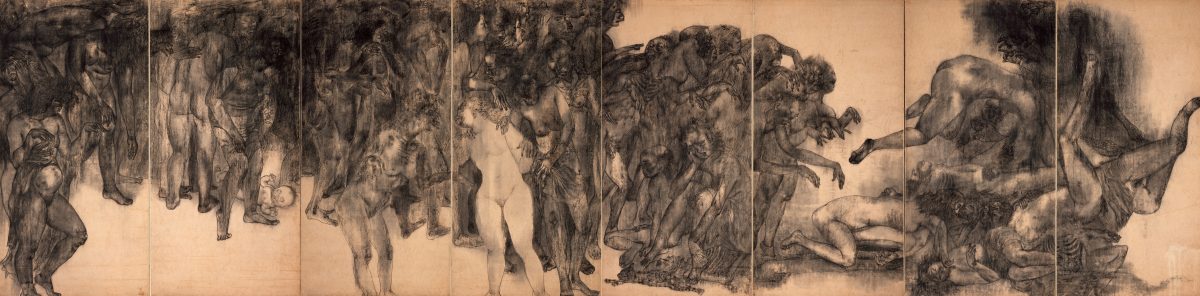

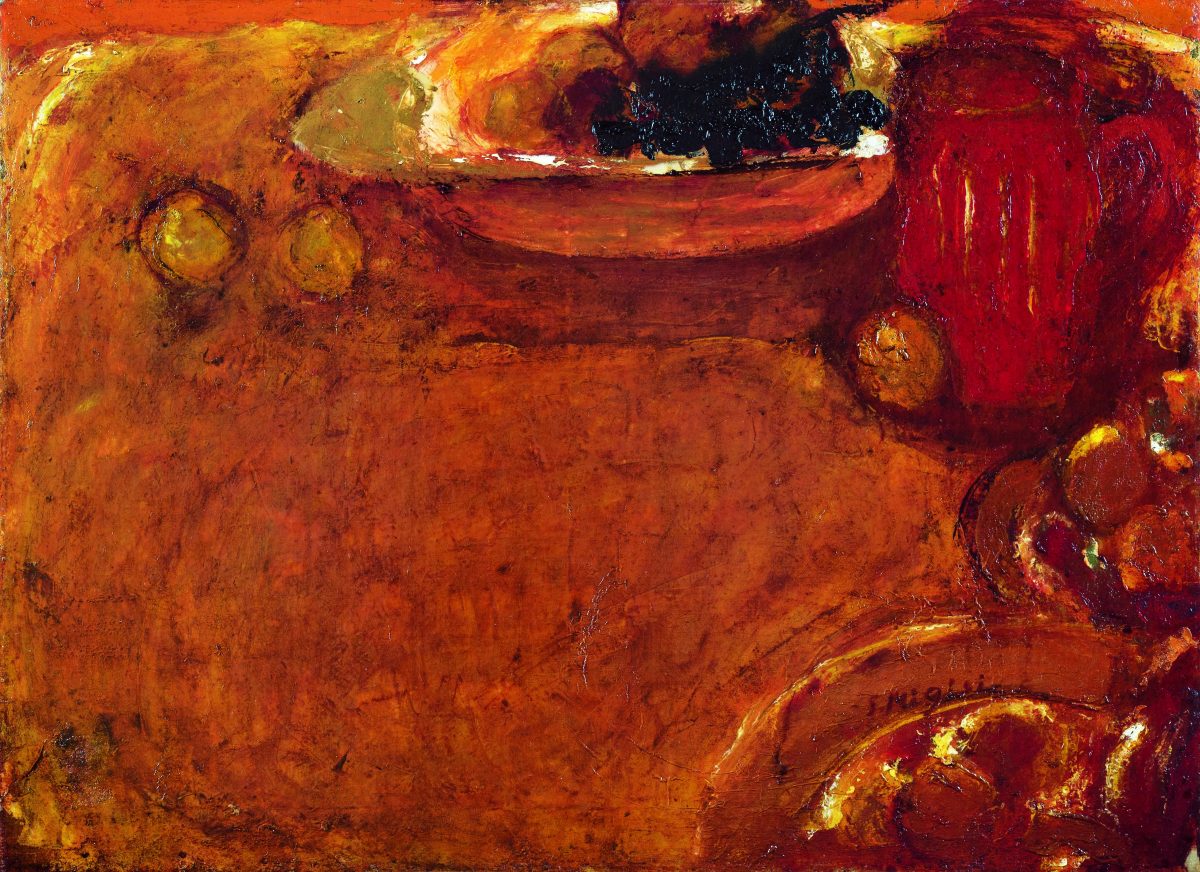

Volk also presents engrossing accounts of artists’ strategies for women’s liberation, focusing on artists Migishi Setsuko and Akamatsu Toshiko. Both worked in oil and actively participated in national cultural debates on the difficulties women artists faced in the postwar period, in publications such as the Women’s Democratic Newspaper and exhibitions led by the Association of Women Artists and others. But Volk shows that their approaches differed fundamentally: Migishi pursued painterly subjectivity, as seen in the energetic modernist and abstract painting “Still Life (Seibutsu)” (1948). In contrast, Akamatsu considered art inseparable from its audience. Her riveting series Atomic Bomb Pictures (1950–82), created with Maruki Iri and later known as Ghosts, merged Japanese-style ink painting with Western figurative techniques and was intended as collective memorials for public spaces.

Cover of Bi no kuni (March 1948), featuring Onchi Kōshirō, “White Flower: Magnolia (Shiroi hanamagunoria)”

Though the book can sometimes be dry due to its scholarly nature, its organization, clarity, and dialogue with Japan’s political and social histories make for highly compelling reading. Volk establishes how Japanese monuments of war and peace were anything but simple artifacts of the period, garnering divisive attitudes from the public. For instance, Kikuchi Kazuo’s “Peace Group (Heiwa gunzō)” (1950), a trio of three nude female figures representing love, will, and intelligence commissioned for the city of Tokyo, enjoyed relative success. But the nude male sculpture “Voices of the Sea (Wadatsumi no koe)” (1950) by Hongō Shin, commemorating student-soldiers killed in the war, was highly controversial; the work was admired as a peace symbol but also criticized by art institutions and the public for its glamorization of Japan’s own aggressive history of war.

In the Shadow of Empire’s key takeaway is grand and clear: Attitudes toward the study of Japanese art from the occupied period need to change. Rather than being relegated to a lesser period of art history, these works need to be foregrounded as critical objects of political negotiation and cultural conversation in modern East Asia.

Akamatsu Toshiko and Maruki Iri, “Ghosts (Yūrei)” (1950), first painting in the series Atomic Bomb Pictures (1950), mounted as eight-panel folding screen, ink on paper

Akamatsu Toshiko and Maruki Iri, “Ghosts (Yūrei)” (1950), first painting in the series Atomic Bomb Pictures (1950), mounted as eight-panel folding screen, ink on paper

Migishi Setsuko, “Still Life (Seibutsu)” (1948), oil on canvas

Hongō Shin, “Voices of the Sea (Wadatsumi no koe)” (1950), bronze, later cast

In The Shadow of Empire: Art in Occupied Japan, written by Alicia Volk and published by the University of Chicago Press, is available for purchase online and in bookstores.

AloJapan.com