A quarter of a million people were in Nagasaki when the atomic bomb exploded, sharing the same experience as Chiyoko Iwanaga. She was nine years old when the American bombers appeared overhead in August 1945, and she saw the blinding flash, the burning city and the clouds that turned the summer sky dark.

Six and a half miles from the hypocentre of the blast, Iwanaga suffered no direct injury, but days later her face swelled up, her gums bled and her hair fell out — the symptoms of radiation sickness. She recovered, but has suffered throughout her life with thyroid problems. Members of her family, including her mother, had cancer.

But for all the sufferings that they have in common, Iwanaga is different from many of the other survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Iwanaga has spent years arguing that she should be entitled to support from the government

SHOKO TAKAYASU FOR THE TIMES

Hibakusha, as atomic bomb survivors are called in Japanese, receive valuable financial support from the government, including free healthcare and a monthly pension. These have largely been denied to Iwanaga, and others like her, by the arbitrary rulings of bureaucrats.

If she had been a few hundred metres to the east when the bomb fell, she would have received lifelong free medical care. People who were further away than her — as far as seven and a half miles from the hypocentre — qualify as hibakusha, while she does not.

• How the atomic bombs devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The benefits enjoyed by hibakusha are available only to those who meet strict conditions. Most of them are people who were inside specific areas at the moment of the explosion, or who entered them soon afterwards when radiation levels were still high.

The hibakusha zone was defined not by the physical damage or measurements of contamination, but simply by existing local government boundaries.

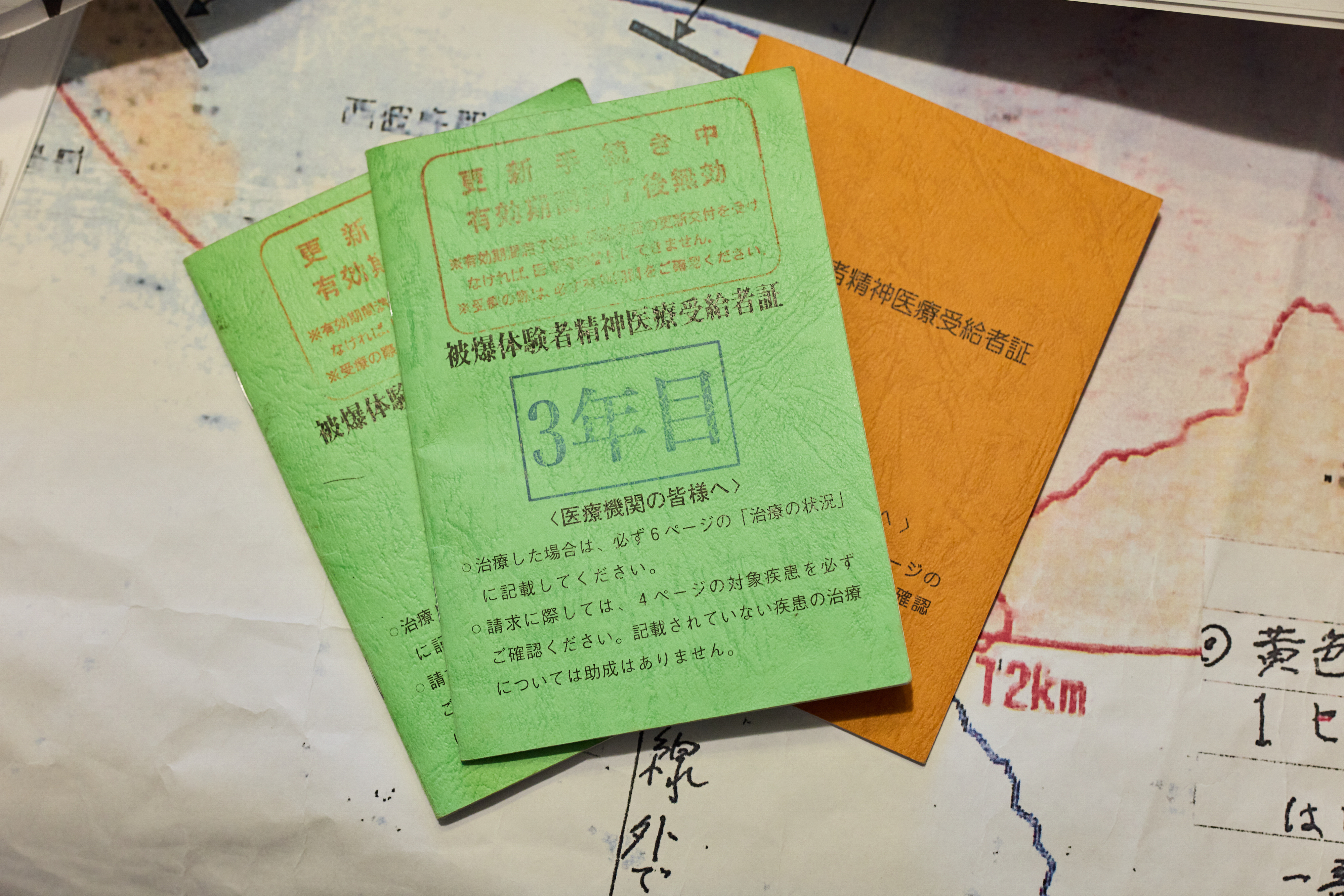

Iwanaga’s certificate of mental healthcare and an atomic bomb survivors’ book

SHOKO TAKAYASU FOR THE TIMES

For 18 years Iwanaga has been leading a group of hundreds of similarly excluded people who are suing the government for official recognition. All of them, by definition, are at least 80 years old; many are unwell and some have died as the cases have slowly ground through the courts.

“Everyone is getting old, extremely old,” Iwanaga, 89, said in her home in Nagasaki. “There are people suffering from very serious illness. If nothing changes soon it will be too late.”

The conflict arises because of the dastardly character of the atomic bomb, which killed people slowly as well as fast. Those closest were vaporised by heat and the blast wave, or suffered terrible burns that killed them after hours or days. Many others died slowly and lingeringly from radiation sickness, or decades later from cancers and other illnesses caused by exposure.

The distribution of fallout was uneven and depended on various factors, including geography and weather — the notorious radioactive “black rain” fell on outlying regions where the bomb had hardly been felt.

The destruction in central Nagasaki

MPI/GETTY IMAGES

Local governments needed a clear formula for differentiating those who deserved support from those who did not. Over the years, they defined a zone based on city and municipal boundaries, adjusted and expanded over the years.

Those who were within the zone are entitled to free medical check-ups and treatment (Japan’s national insurance scheme covers only two thirds of costs for the rest of the population). Depending on their state of health, many hibakusha get a monthly payment of between £175 and £730, as well as support for nursing homes and even funeral costs. Over the course of a lifetime the benefits can amount to hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Since the system was introduced in 1957, the number of registered hibakusha has been as high as 372,000, but many others have not been able to prove their eligibility.

In the chaos and destruction, some lost not only their homes and families but anyone who could testify that they were where they claim to have been.

• ‘To understand the horrors of Hiroshima, you had to live through it’

The government eventually extended the eligible area to a radius of 12km (7.5 miles) from the hypocentre, but those on the outer edges of this zone have to prove damage to their health caused by the bomb.

Iwanaga points to the bleeding and hair loss that she suffered in the days afterwards, symptoms, she believes, of radiation sickness caused by drinking contaminated water.

Successive Japanese courts have rejected this on the grounds that they could also have been caused by another curse of the times — child malnutrition. But if she had been within the boundaries of Nagasaki city, rather than in the neighbouring municipality of Fukahori, the question would arise.

“This is an obvious injustice,” Mika Nakashiki, a lawyer acting for Iwanaga and other plaintiffs, said. “An atomic bomb doesn’t care about municipal divisions.”

Mika Nakashiki

SHOKO TAKAYASU FOR THE TIMES

Last September the Nagasaki district court ruled in favour of 15 out of 44 plaintiffs who were claiming their rights as hibakusha, although Iwanaga was not one of them.

Both sides are appealing against the verdict, but time is on the side of the government. Two of the 15 victors have since died. “I’m already wobbly on my feet,” said Iwanaga, who will be 90 in January. “But I have to speak up for those who can no longer move.”

AloJapan.com