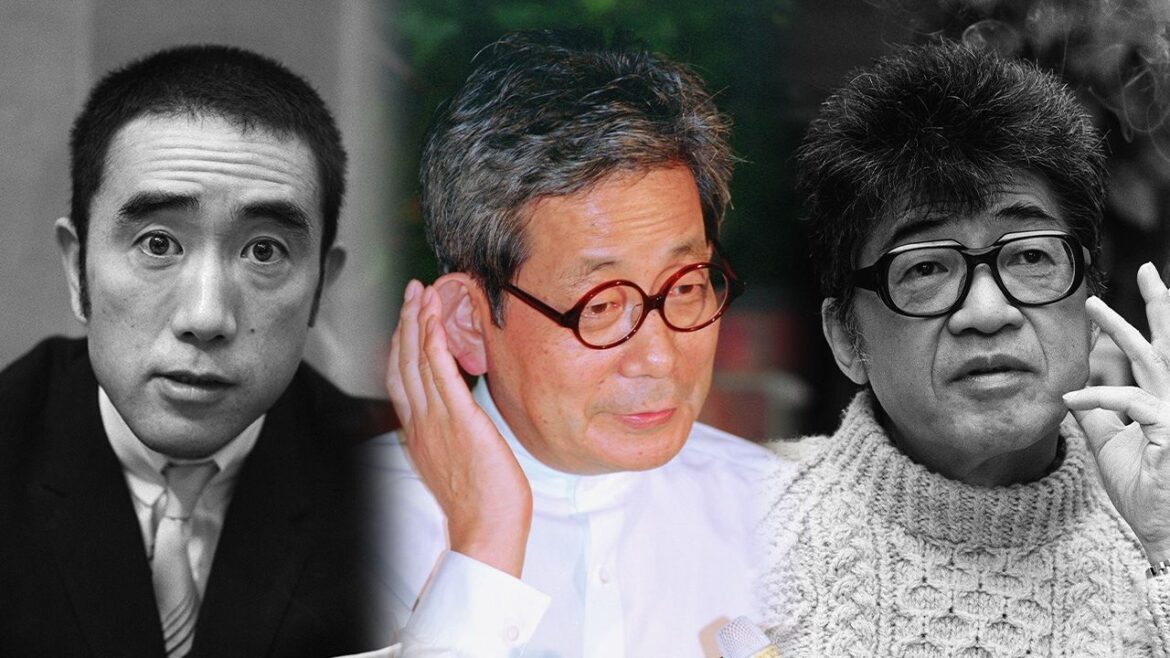

As Japan moved from a period of occupation and postwar reconstruction into an era of rapid economic growth from the mid-1950s, brilliant new writers like Mishima Yukio, Ōe Kenzaburō, and Abe Kōbō made their mark on the literary scene.

This third instalment of a series on Japanese literature in the Shōwa era (1926–89) focuses on books written from 1955 to 1964 (Shōwa 30–39). As the country enjoyed a period of rapid economic growth, new writers emerged to reshape the literary landscape.

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Mishima Yukio

A Japanese edition of Kinkakuji (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) by Mishima Yukio. (© Shinchōsha)

Mishima Yukio (1925–70) was 24 years old and an employee at the Ministry of Finance in 1949, when he burst on to the literary scene with his semiautobiographical novel Confessions of a Mask. With The Sound of Waves (1954), he became a bestselling author. His next major work—The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), which takes inspiration from the real-life burning of the pavilion at the Kyoto temple of Kinkakuji—is a daring attempt to tear down traditional ideas of beauty in Japan.

The main character Mizoguchi was born on a lonely cape projecting into the Sea of Japan. From an early age, his father, the priest of a temple on the cape, tells him that there is nothing on this earth so beautiful as Kinkakuji. Mizoguchi has a stutter and an inferiority complex about his appearance, so other children laugh at him and he becomes withdrawn.

Mizoguchi’s father entrusts the boy’s future to the head priest of Kinkakuji, with whom he had studied before entering the priesthood. After his father dies in the later stages of World War II, Mizoguchi follows his wishes and becomes an acolyte at the temple. While its overwhelming beauty comes to capture his heart, his emotions are complex, combining hatred with his longstanding adulation. He becomes ecstatic with visions of the temple consumed by flames in a firebombing raid.

Beauty and destruction are two sides of the same coin. But Kyoto is spared firebombing and the temple does not burn. “Never had the temple displayed so hard a beauty—a beauty that transcended my own image, yes, that transcended the entire world of reality, a beauty that bore no relation to any form of evanescence,” Mizoguchi thinks in astonishment after the announcement of Japan’s surrender (taken from the translation by Ivan Morris).

Mizoguchi becomes a priest and studies at a Buddhist university, but starts to run wild. He distances himself from the head priest who has been looking out for him, and speeds toward catastrophe, obsessed by the thought, “I must set fire to the Golden Temple.”

In 1970, Mishima killed himself by seppuku amid a botched attempt to instigate a coup. There is a scene where Mizoguchi says, “Knowledge can never transform the world . . . What transforms the world is action.” What question was Mishima trying to ask through his depiction of beauty?

Kinkakuji is translated as The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Ivan Morris.

Kamen no kokuhaku is translated as Confessions of a Mask by Meredith Weatherby.

Shiosai is translated as The Sound of Waves by Meredith Weatherby.

Season of Violence by Ishihara Shintarō

The Korean War broke out in June 1950, and even as Japan regained its independence from occupation in the San Francisco Peace Treaty in September the following year, the Cold War was intensifying. In 1960, Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke signed the Japan-US Security Treaty, sparking mass protests that drew in young people.

A Japanese edition of Taiyō no kisetsu (Season of Violence), a collection including the title story by Ishihara Shintarō. (© Shinchōsha)

Around this time of volatile politics, Ishihara Shintarō (1932–2022), while still a student at Hitotsubashi University, shot to fame with the publication of the novella Season of Violence (1955), which shocked Japanese society as an “immoral” work that shattered the values of the day. While it drew mixed reactions, the story was chosen as the winner of the Akutagawa Prize, making Ishihara the youngest recipient of the award. The Japanese title literally means “season of the sun,” and the story became associated with a subculture of rebellious young people called the “sun tribe.”

The main character, Tatsuya, is a high school student who spends his days boxing and sailing. He is preoccupied by women, deals, fighting, and intimidation. He has people he spends time with, but his relationships are calculated and he does not believe in friendship.

Tatsuya’s girlfriend is called Eiko, but she means nothing to him. He thinks that love is not a lasting emotion, but just something that burns during physical passion. Throughout, Tatsuya lives his life as a rebel, acting only for the moment. Ishihara writes of how the young people detest adult morals and think of virtue as dreary and boring.

What are they seeking from the era? After Tatsuya gets Eiko pregnant, the work builds to an ending that expresses Ishihara’s macho attitudes.

Taiyō no kisetsu is translated as Season of Violence by John G. Mills, Toshie Takahama, and Ken Tremayne.

The Age of Our Own by Ōe Kenzaburō

Another early starter, Ōe Kenzaburō (1935–2023) made his literary debut while studying French literature at the University of Tokyo. He was still just 23 years old when he started writing Warera no jidai (as yet, it has not been translated into English, but the film adaptation has the English title The Age of Our Own). This wild work, with the freshness of youth, deliberately incorporated extreme sexual expressions and violent descriptions, and it was met with a scathing reception from the literary establishment.

A Japanese edition of Warera no jidai by Ōe Kenzaburō. (© Shinchōsha)

Five years later, when it appeared in paperback, Ōe wrote of how deeply he loved the novel, and that he was the only person who could write it. Ōe would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 1994, and among his creative output, this work is an unpolished gem.

It tells the story of two brothers in parallel. Yasuo is a French literature student at university who lives with a middle-aged prostitute called Yoriko who caters to foreign clients. Although he is weary of his sex life with her, with no future prospects, he resigns himself to the situation.

His one faint hope is that if he can win an essay contest that he entered—then he will have the chance to study in France for three years. If he escapes from Japan, he will be able to break up with Yoriko and start a new way of life.

His 16-year-old brother Shigeru is the pianist for a jazz trio called the Unlucky Young Men, alongside the 16-year-old clarinetist Kōji and the drummer Kō, a 20-year-old ethnic Korean who has returned from the Korean War. The young musicians perform at underground clubs, seeking excitement and pursuing hedonism.

By chance, they get involved in a demonstration by a right-wing group and catch sight of the emperor in his motorcade. They want to shock this “quiet man” who, for them, symbolizes exhaustion and weakness. Based on this motivation alone, they plan to throw a hand grenade—which Kō has been hiding—in front of the motorcade.

Ōe writes that “there was no future for young people in Japan.” but seems to long for his characters to overturn the status quo. He asks whether escapism is all that is left for them.

Yasuo’s and Shigeru’s choices lead them to their respective fates. This powerful work depicts the life of young people of the era in a way that is quite different from Ishihara’s novella.

The Woman in the Dunes by Abe Kōbō

A Japanese edition of Suna no onna (The Woman in the Dunes) by Abe Kōbō. (© Shinchōsha)

Abe Kōbō (1924–93) was born in Tokyo, but raised in Manchuria, where his doctor father worked. He studied medicine at Tokyo Imperial University, but although he graduated following the end of World War II, he did not himself become a doctor, instead pursuing literary activities. He won the Akutagawa Prize for “The Crime of S. Karma,” the opening story in his 1951 collection The Wall. While he focused on writing plays in the early days, the 1962 novel The Woman in the Dunes became one of his best-known works.

“One day in August a man disappeared.” In the book’s opening, we hear of how a man had set out for the seashore to collect specimens of insects living in the sand dunes. If he discovered a new variety, his name would be immortalized in books alongside the Latin name of the insect that he found.

However, the man falls victim to the designs of local villagers and is trapped in a dilapidated house at the bottom of a hole; it is 20 meters up to ground level, but the rope ladder has been taken away. An uncommunicative woman lives in the house and each night she silently shovels up sand. The villagers lower a basket from above, into which the woman puts kerosene cans packed with sand.

The sand flows into the hole like a living creature. If it is left uncleared, the man and woman will be buried alive—the sand could even swallow the village. The woman cannot handle the work alone, which is why the man was shut in with her to assist with her task.

A hellish life begins. When the man tries to climb out of the hole, his feet sink into the soft sand. He is in anguish, but he takes on the mindless labor of shoveling in exchange for food and water. There is a superb scene of attempted escape. What will happen to the man in the end?

While the novel is a fantastic, bizarre fable, it has a convincing universality. In the real world, we are unable to break free from lives shackled to the thinking of our day. Is our only option to compromise and cling on to hope? The Woman in the Dunes has now become part of world literature, with translations into more than 20 languages. After Abe’s death, it emerged that he had been considered as a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Suna no onna is translated as The Woman in the Dunes by Dale Saunders.

“S. Karuma shi no hanzai,” from Kabe (The Wall), is translated as “The Crime of S. Karma” in the collection Beyond the Curve by Juliet Winters Carpenter.

Tokyo Express by Matsumoto Seichō

The mystery writer Matsumoto Seichō (1909–92) was born in the same year as Dazai Osamu, but unlike the No Longer Human author, he was raised in poverty. After leaving school at 15, he worked a series of jobs before getting a position at the daily Asahi Shimbun. He was then drafted and spent much of World War II in Korea. His career as an author only began at 41, when he won a prize for his short story “Saigō satsu” (Saigō’s Currency).

A Japanese edition of Ten to sen (Tokyo Express) by Matsumoto Seichō. (© Shinchōsha)

Tokyo Express (1958) was a landmark bestseller and a pioneer in “social mystery,” which incorporates social issues into the mystery genre.

Yasuda, the president of an industrial machinery company, is at platform 13 of Tokyo Station with some waitresses he knows from a restaurant. When they look over to platform 15, there is another waitress from the same restaurant with a young man, and they board a limited-express train for Hakata in Kyūshū. The two appear to be lovers.

A week later, two corpses are found at the Hakata coast. The man is the deputy director of a ministry embroiled in a corruption scandal, but due to the circumstances at the scene of death, it is ruled to be a double suicide. There are witness testimonies at Tokyo Station.

Mihara, the young detective in charge of the corruption investigation, is not convinced by the suicide verdict. He wonders whether it is really possible to see people by chance on another platform at Tokyo Station where trains are always coming and going. When he checks the timetable, there is just a four-minute window for which platform 15 would be visible.

Yasuda had regular dealings with the ministry, but he was on a business trip to Hokkaidō at the time of the supposed suicide. The breaking down of this alibi is one of the greatest pleasures of the novel. Real-life postwar bribery scandals involving politicians, businessmen, and bureaucrats gave a persuasive power to the author’s depiction of the background to the case and the criminal motivations.

Matsumoto’s mysteries focus on social issues and motivations, and this is why the detailed descriptions of the characters’ crimes resonate with many readers. The author, who had suffered hardship himself, shone a light on social unfairness and injustice.

His masterpiece Point Zero handles the issue of prostitution targeting the occupying forces in the immediate postwar era, while Inspector Imanishi Investigates is a tragedy based on the discrimination against people with Hansen’s disease (once known as leprosy). Older than other writers who emerged in postwar Japan, Matsumoto presented a different perspective on the era.

Ten to sen is translated as Tokyo Express by Jesse Kirkwood and Points and Lines by Makiko Yamamoto and Paul C. Blum.

Zero no shōten is translated as Point Zero by Louise Heal Kawai.

Suna no utsuwa is translated as Inspector Imanishi Investigates by Beth Cary.

Selected Japanese Literature (1955–64)

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Mishima Yukio, translated by Ivan Morris from Kinkakuji (1956)

Season of Violence by Ishihara Shintarō, translated by John G. Mills, Toshie Takahama, and Ken Tremayne from Taiyō no kisetsu (1956)

Tokyo Express by Matsumoto Seichō, translated by Jesse Kirkwood from Ten to sen (1958)

Warera no jidai (The Age of Our Own) by Ōe Kenzaburō (no English translation) (1959)

Inspector Imanishi Investigates by Matsumoto Seichō, translated by Beth Cary from Suna no utsuwa (1961)

The Woman in the Dunes by Abe Kōbō, translated by E. Dale Saunders from Suna no onna (1962)

Ai to shi o mitsumete (Gazing at Love and Death) by Ōshima Michiko and Kōno Makoto (no English translation) (1963)

Pari moyu (Paris is Burning) by Osaragi Jirō (no English translation) (1964)

Saredo warera ga hibi (Anyway, That Was Our Time) by Shibata Shō (no English translation) (1964)

A Personal Matter by Ōe Kenzaburō, translated by John Nathan from Kojinteki na taiken (1964)

Note that some works have multiple translations, but only one is given for each in this list.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 8, 2025. Banner photo: From left, Mishima Yukio, Ōe Kenzaburō receiving the Nobel Prize, and Abe Kōbō. All © Jiji.)

AloJapan.com